drawing, paper, ink

#

drawing

#

imaginative character sketch

#

light pencil work

#

pencil sketch

#

mannerism

#

cartoon sketch

#

figuration

#

paper

#

personal sketchbook

#

ink

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

pen-ink sketch

#

sketchbook drawing

#

history-painting

#

storyboard and sketchbook work

#

nude

#

sketchbook art

Dimensions: height 264 mm, width 166 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

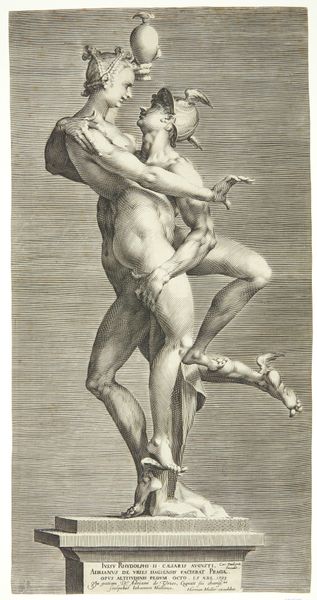

Curator: The tension in this piece, it's just breathtaking, isn't it? Editor: It certainly evokes… something. It's Bartholomeus Spranger's "The Rape of the Sabine Women," created around 1595, residing now in the Rijksmuseum. Pen and brown ink on paper, with a gray wash. But let’s talk about that tension you mentioned. Curator: Well, look at the… struggle. The way the woman is drawn, clearly unwilling, yet being carried off. You feel her resistance. I wonder what paper and ink were available, and what would dictate the amount, and cost, of this drawing for Spranger to create. Editor: Note how Spranger focuses on the figures, set against an undefined ground. This concentrates our gaze and heightens the emotional drama of the composition itself. The very starkness seems deliberate. The musculature! The exaggeration! What's your analysis of Spranger’s choice in those details, if any? Curator: Everything serves a purpose. The physicality is the point; labor is apparent. A clear study of process over everything. This was for wealthy, elite people who never touched this ink. I question if they saw, understood, or cared how artworks were actually created. Editor: The dynamism is really remarkable here. The composition spirals upwards, pulling our eyes along with the figures, almost mimicking the violence of the act depicted. Does it make a comment, perhaps about movement as coercion? Curator: I appreciate your formal approach to understand Spranger. For me, though, seeing the work, and then researching all of the social and economic strata of 16th century artwork just reinforces what my interpretation of artworks usually are: to reflect a class distinction. Editor: That’s a thought-provoking analysis. In that lens, seeing this historical, complex scene now reminds one about the history of oppression and dominance; you’ve given a framework for interpreting the composition. Curator: Exactly! I am looking forward to more insight next week from a Feminist viewpoint. It seems really interesting. Editor: Me too, I'm eager to explore how this Mannerist style intersects with narrative—the stories we tell, and how they shape perception.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.