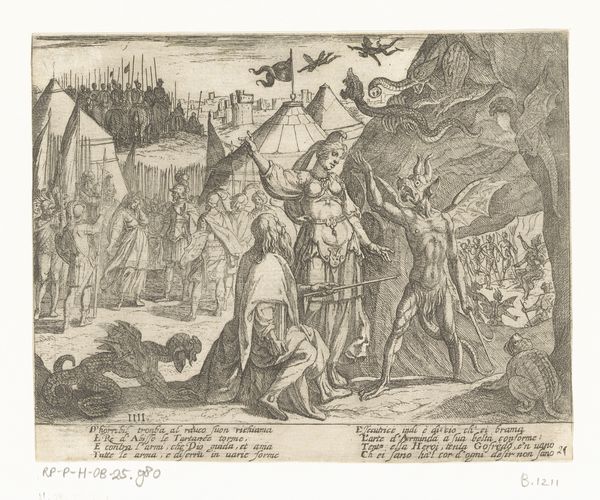

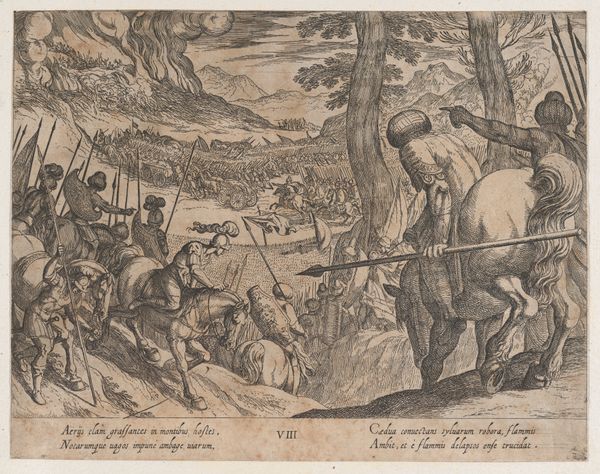

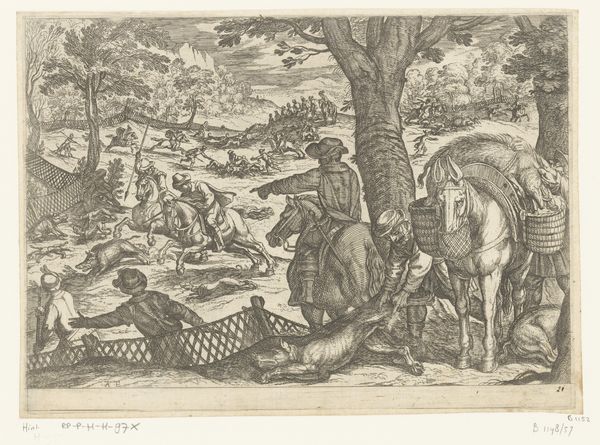

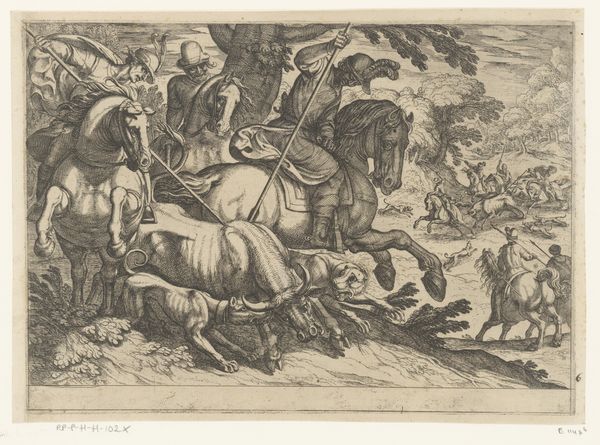

Illustratie bij Canto XIII van Tasso's 'Gerusalemme Liberata' 1565 - 1630

0:00

0:00

antoniotempesta

Rijksmuseum

drawing, print, etching, ink, engraving

#

drawing

#

ink drawing

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

#

pen drawing

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

ink

#

geometric

#

history-painting

#

italian-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 145 mm, width 183 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

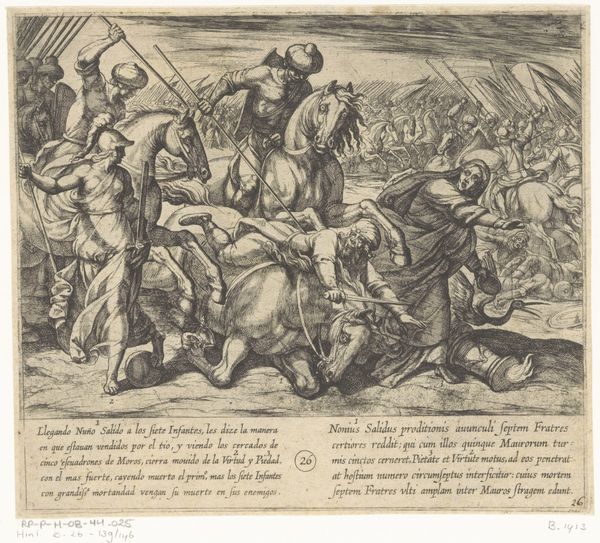

Editor: So, this is Antonio Tempesta’s "Illustration for Canto XIII of Tasso’s ‘Jerusalem Delivered’," created sometime between 1565 and 1630. It's an ink drawing and etching. The scene is filled with activity – building, mourning, attending to the horses… It feels very busy and narrative-driven. What do you see in this piece? Curator: I see a deeply layered commentary on the social costs of war and religious fervor. It is important to recall that Tasso’s epic poem itself, written during the Counter-Reformation, is filled with religious and political propaganda about crusades against the Ottoman Empire. What, or who, seems to be the focus here? Editor: My eye is drawn to the fallen horse in the foreground – its size and position. Also, some of the figures mourning on the side, with their gestures… it conveys a clear emotion, a clear loss. Curator: Exactly. The horse becomes a symbol of innocence, an unacknowledged victim, literally crushed by the weight of the crusades. And look at the almost feverish frenzy with which the men are rebuilding the war machinery. It is meant to illustrate specific canto details, but consider the message the artist is sending through its composition and style. Isn't he juxtaposing the mourning over a fallen animal with the eager preparation for more violence? Editor: Yes, I see that tension now. The horse as a victim really highlights the human cost as well. The so-called ‘heroic’ efforts are happening at the expense of lives and suffering for all beings, non-human too. Curator: Precisely. Tempesta subtly critiques the glorification of war inherent in Tasso's poem by centering those most vulnerable to it. Think about it; how often do historical narratives overlook the quiet suffering of ordinary people, animals and resources to further political ambitions? Editor: I never thought of looking at a historical illustration like this. This approach shifts my understanding. It’s not just illustrating a text, but making a statement about power. Curator: Indeed. The beauty of engaging with art this way is that it empowers us to see the world, both past and present, with more critical eyes, and also demands we question every aspect, even what is supposed to be the established narrative.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.