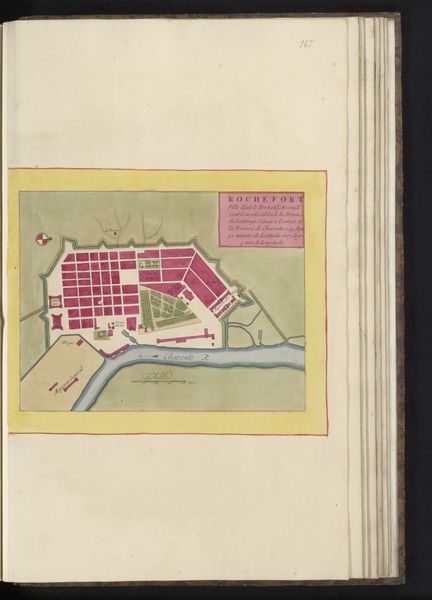

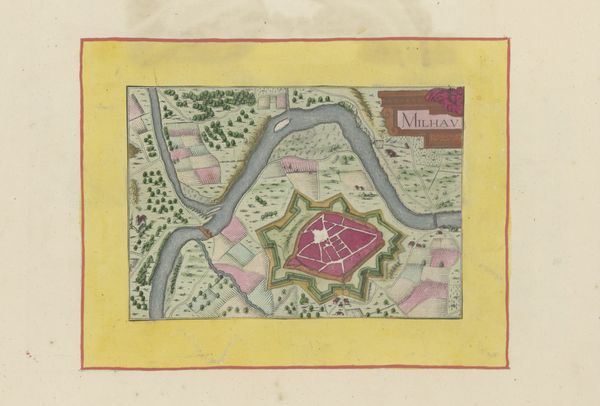

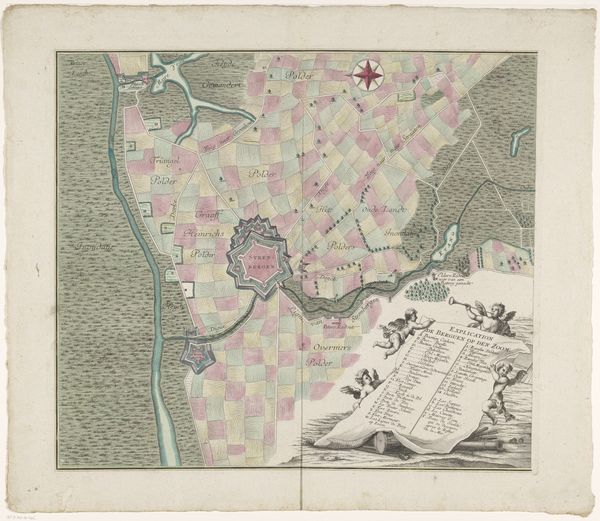

painting, watercolor

#

narrative-art

#

dutch-golden-age

#

painting

#

landscape

#

watercolor

#

geometric

#

cityscape

#

watercolour illustration

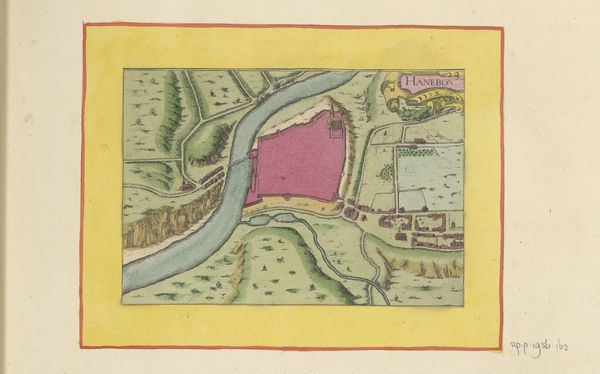

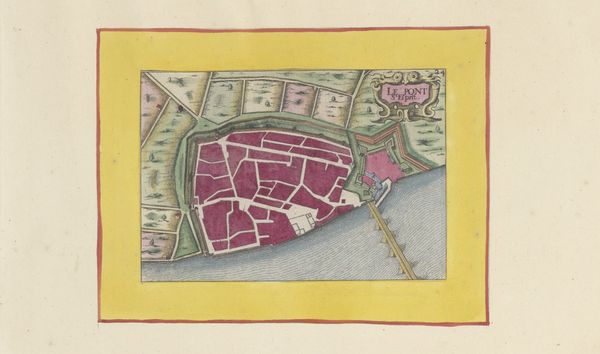

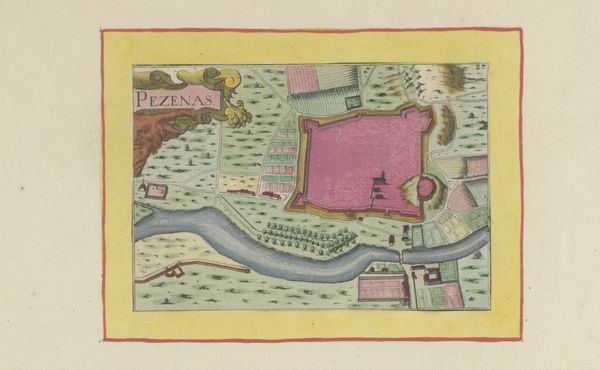

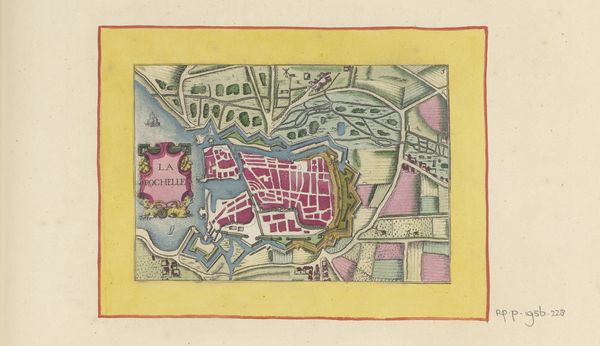

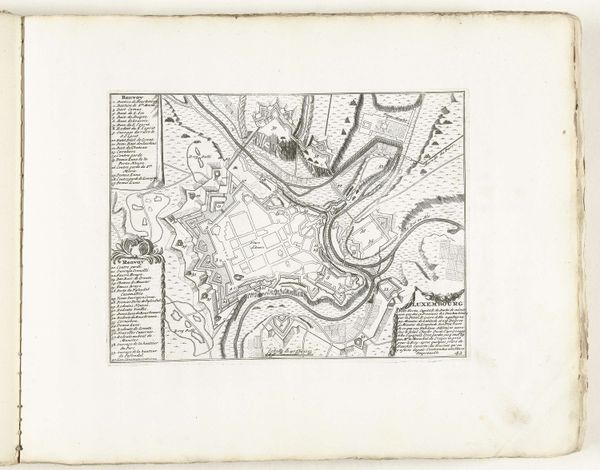

Dimensions: height 103 mm, width 150 mm, height 532 mm, width 320 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, here we have an anonymous 17th-century watercolour illustration entitled "Vestingplattegrond van Libourne," or "Fortification Map of Libourne" from 1638. The intense pink colour dominating the centre is really striking. How do you interpret this work? Curator: That pink, for me, speaks volumes. Beyond mere aesthetics, consider what it represents within the context of 17th-century cartography. Maps were instruments of power, used to delineate territory, control populations, and project authority. The vibrant pink—likely artificial, not ‘natural’—could symbolize the coloniser’s imposed vision, transforming the landscape into something easily consumed and controlled. Think about the social implications of depicting a place not as it *is*, but as a tool for those in power. What does this flattening mean for the inhabitants? Editor: That's a really interesting point. It's easy to just see it as a pretty picture, but the pink does seem to impose a certain artificiality onto the scene. It’s almost…performative. Do you think that it serves as a kind of… symbolic warning of those boundaries and, potentially, consequences of crossing it? Curator: Precisely! And let’s consider the “fortification” aspect. Who were these fortifications *for*? Who were they keeping *out*? The map is silent on the experiences of those who may have resisted this imposed order. Maps are never neutral; they are always telling a story from a particular viewpoint. Think about the indigenous populations; what might a map *they* created have looked like? Whose stories are being prioritised? Editor: This definitely shifts my perspective. It is more than just a landscape or nice colours, it's about power, control, and who gets to write history – or, in this case, draw the map. Curator: Exactly. Questioning these seemingly objective representations helps us to unravel the complex narratives woven into the very fabric of our understanding of the world. It allows us to understand that landscapes contain historical echoes of identity, gender, race, and politics.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.