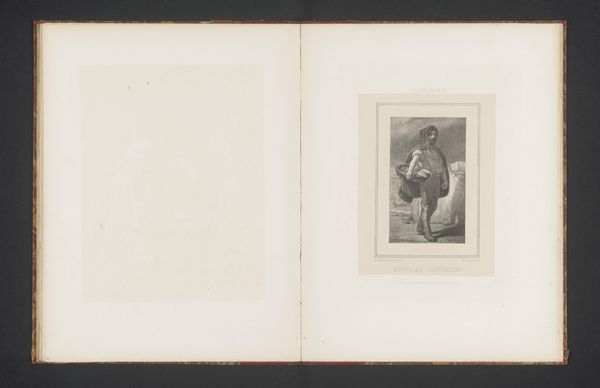

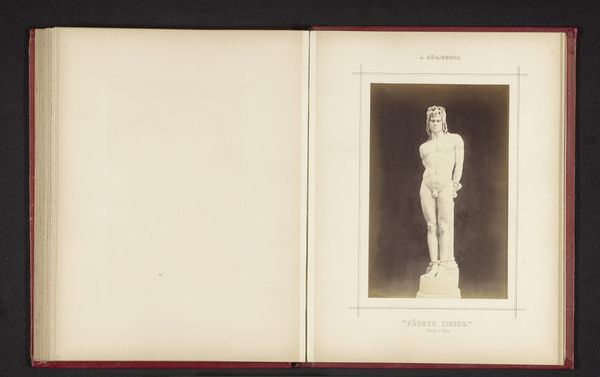

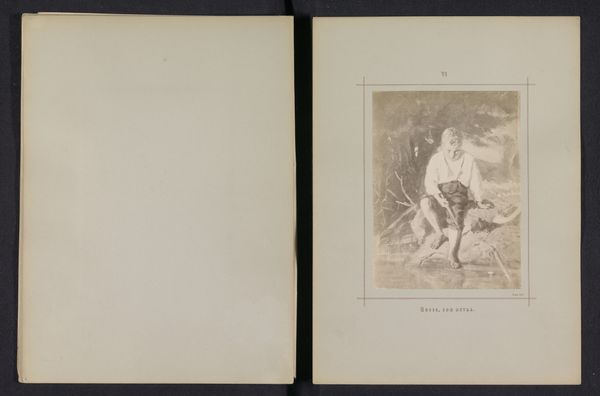

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

nude

#

realism

Dimensions: height 132 mm, width 82 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: What we have here is a rather unsettling portrait, a gelatin-silver print from around the 1860s, titled "Portret van een onbekende man die lijdt aan psoriasis," or "Portrait of an Unknown Man Suffering from Psoriasis," by A. de Montméja. Editor: The starkness of it grabs me right away. The subject’s posture, arms crossed protectively... you immediately sense a vulnerability, a kind of imposed exposure. The way this gelatin-silver print renders detail so clinically – it feels deliberate. Curator: Montméja wasn’t aiming for conventional beauty, that's for sure. As a realist photographer, I'd guess that his intentions were directed towards documentation, with perhaps a subtle commentary on societal perceptions of the ill or 'afflicted.' It seems like there may even have been a scientific drive, or possibly commissioned, given the level of... unflinching detail, Editor: The social context of image-making at that time makes you wonder. Gelatin-silver prints were becoming more commonplace, enabling higher volumes of image production, greater fidelity, which democratized visual representation...or further objectified the vulnerable. It's this friction between expanding technical capacity and lingering societal stigma that’s key. Think about who held power in that period and who were subjects for observation—there are parallels to be made in present conversations on visibility, illness, and consent. Curator: Right! But I feel there's more than simply that. It's in those shadow nuances on his face. There is a man in suffering, plain to see. Whether Montmeja’s intention was solely clinical or documentary, he’s captured something profoundly human in the texture, beyond the literal representation of the man's ailment. The pose with the arms covering certain elements feels charged in many respects as well—beyond covering just genitals. Editor: And this unflinching gaze also captures the era’s shifting relationship with the human body. Medicine, science, photography--all conspiring to dismantle previous sacred conceptions, forcing us to see both the beautiful and grotesque as existing within a single material form. In many ways, that same discourse is the crux of photography now. Curator: You put it so precisely. A poignant yet confronting window onto then, and a lens through which we must question ourselves today, then. Editor: Exactly. Making an image also implicates who we're making the images for. Who's the audience for it and the kind of agency we afford our subjects?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.