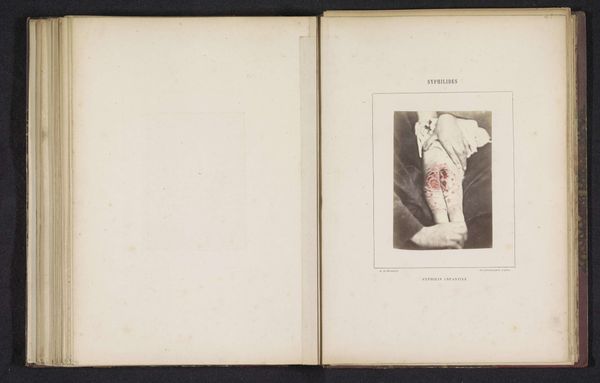

print, photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

# print

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

realism

Dimensions: height 119 mm, width 90 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: I'd like to introduce you to an intriguing, albeit unsettling, piece by A. de Montméja from somewhere between 1860 and 1868. It’s titled "Zwerende huiduitslag op een arm, veroorzaakt door syfilis"—which translates to "Suppurating rash on an arm, caused by syphilis.” It's a gelatin silver print. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: A rush of... unease. There’s a starkness to its realism that I find deeply unsettling. It’s almost like staring directly into the suffering of a forgotten era. The way the light catches the texture… ugh, it's invasive. Curator: Yes, invasive feels apt. It’s a medical photograph, of course, meant for documentation. I’m drawn to how photography, particularly gelatin silver prints, allowed for such detailed—sometimes brutal—representation of the body. We think of photography as truth, but here it's a captured moment of disease made almost hyperreal through the chemistry and craft. Editor: Right. And that hyperreality serves a specific purpose. Who was consuming these images? Were they circulated among doctors as part of their training? Was there a commodification of disease taking place here? Like, how are we meant to *consume* this piece today? Is it edifying or prurient? Curator: Interesting. I think both, perhaps. There’s certainly an element of clinical study at play, maybe scientific curiosity? But, I also can't shake the feeling that there is more to it, it really lingers in your mind. Think of the Victorian fascination with morbidity...the exploration of the darker side of human existence. Perhaps a dark kind of beauty. Editor: Hmm, morbidity as commodity...yes. I wonder what the person whose arm this was received from the exchange. In some ways this photograph exposes the imbalance inherent in the clinical gaze—the patient rendered object, the clinical encounter potentially extractive. And also the technology. To produce this image, Montméja likely relied on an albumen print process to create a reproducible image, before reprinting in gelatin silver. It speaks to a longer, more layered engagement with the infected arm as the print made it material. Curator: Absolutely, it's a dialogue between art, science and social history all rolled into one rather disquieting image. I can see how those technical layers would be so significant in that period too. Editor: I’m still grappling with that uneasy feeling. But I’m walking away knowing it’s important to think through the lens—the camera lens, in this case—and the broader contexts that shaped its creation, dissemination, and enduring impact. Curator: For me, it speaks to how art, even in its most clinical forms, has a unique power to unearth and provoke those raw, complicated, yet very human, emotions. A reminder that there’s a story etched onto every surface, every face, even in a wound.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.