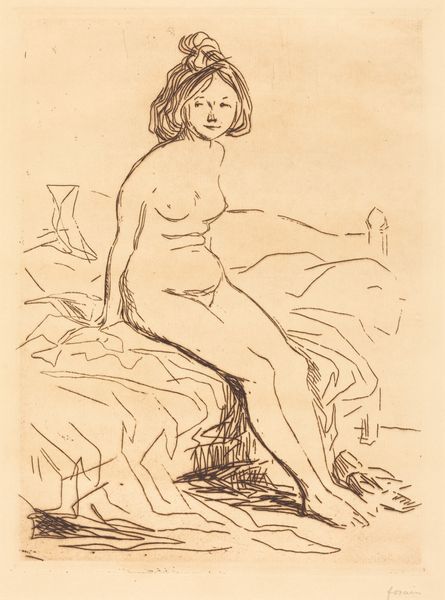

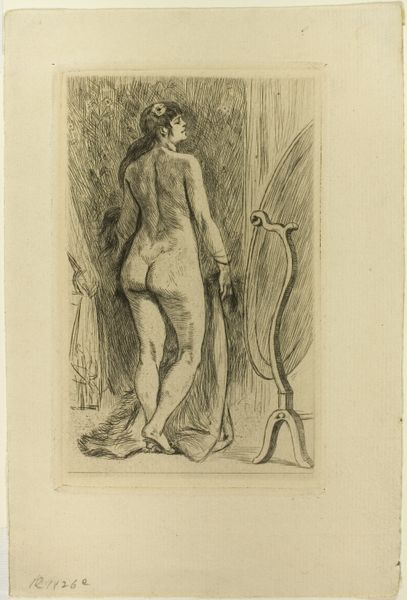

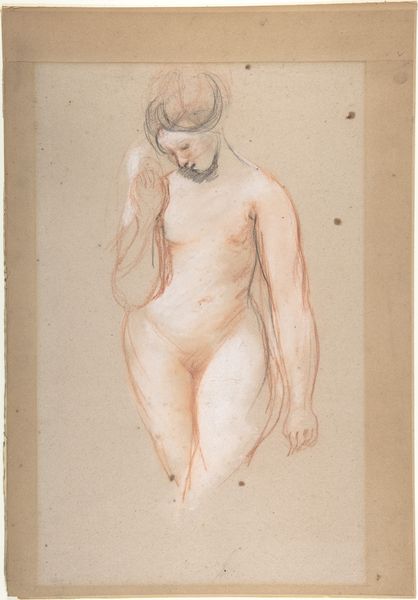

Dimensions: 414 × 351 mm (image); 630 × 461 mm (sheet)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: This is Renoir's "Standing Female Bather" from around 1896, a lithograph in crayon and pencil. It feels so immediate, almost like a sketch rather than a finished piece. I am drawn to the texture of the mark-making. What stands out to you when you look at this? Curator: Well, what immediately grabs my attention is the labor inherent in printmaking versus the spontaneous impression. Think of the social context: Renoir's embrace of lithography challenged the hierarchy separating "high art" from the supposedly lesser crafts. The means of production—the lithographic stone, the specific crayons and pencils—they all leave their mark. Editor: That's fascinating. So the material process itself is part of the meaning? It feels like he's capturing a fleeting moment, not mass producing a commercial image. Curator: Exactly. The physicality of creating the lithograph – grinding pigments, preparing the stone – shapes our understanding of the final "print". What kind of paper was available, what quality, what was its cost? These aren't just aesthetic choices; they reflect the material conditions and social implications of artistic production in Renoir’s time. Notice how he uses the lithographic crayon to mimic the softness of pastel, perhaps elevating a traditionally "feminine" medium. Editor: I never thought about it that way. So instead of just seeing a pretty picture, we're seeing Renoir's relationship to labor, to the art market… Curator: And how this particular intersection affects consumption! Think of the work required for paper manufacturing alone – from raw materials to the printing press. What impact might that have on your assessment of Renoir’s finished product? Editor: This really shifts how I view the artwork. It's less about idealized beauty and more about the nitty-gritty of its creation and distribution, like it embodies some class critique from the era.. Thank you for expanding my understanding. Curator: And thank you. It is easy to divorce art from the industrial. Examining material history returns us to the concrete realities of its creation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.