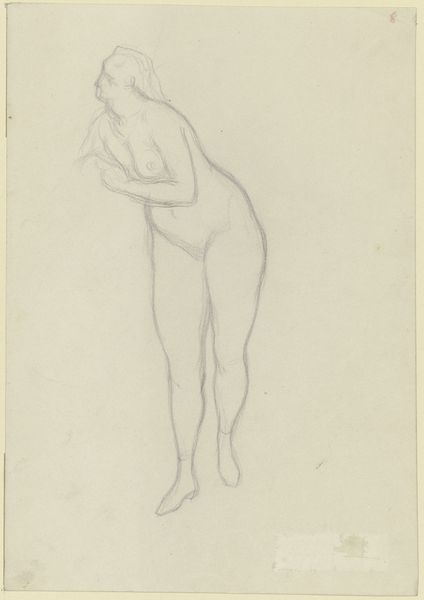

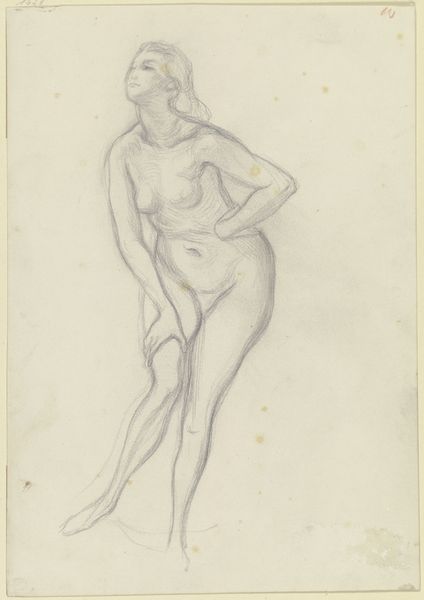

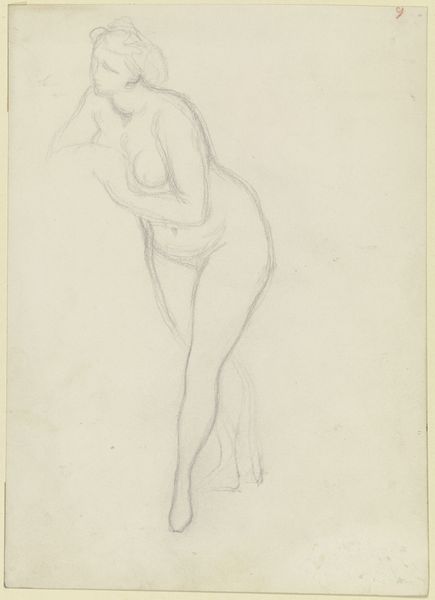

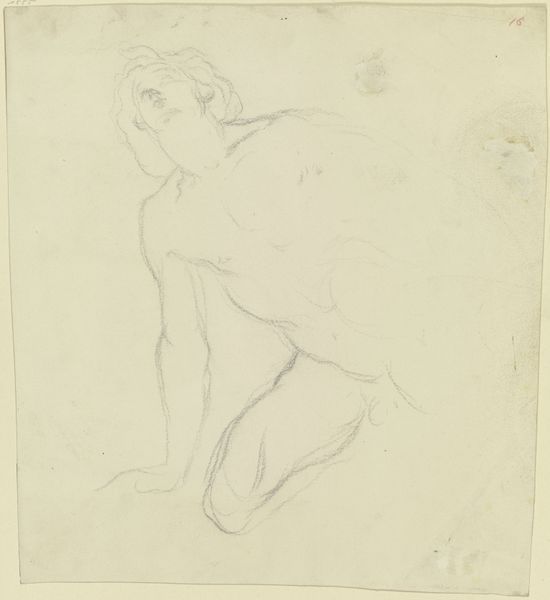

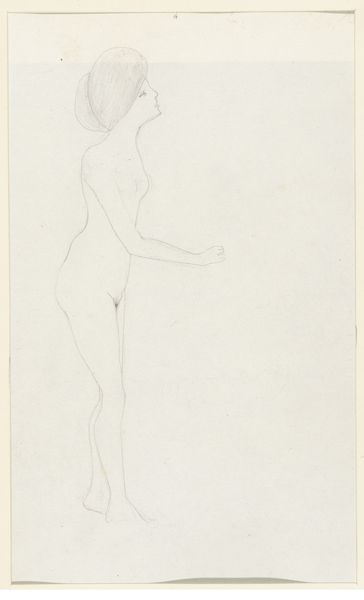

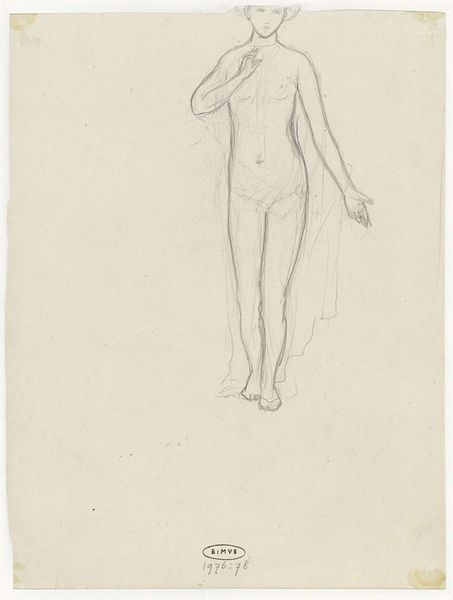

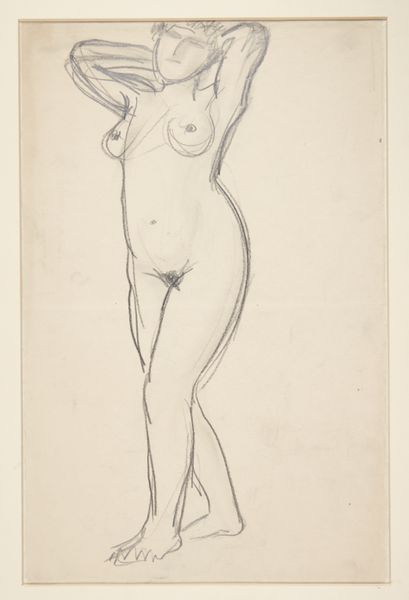

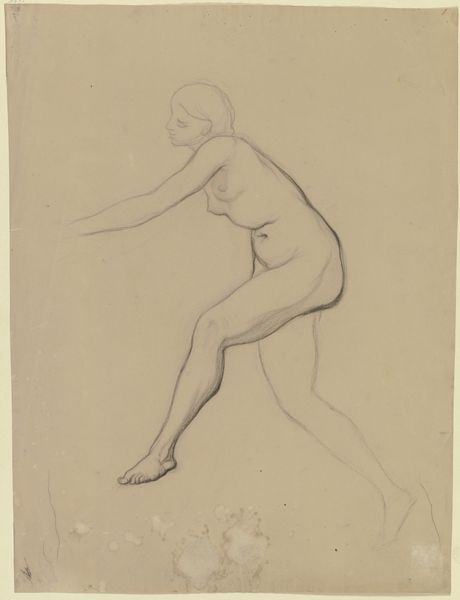

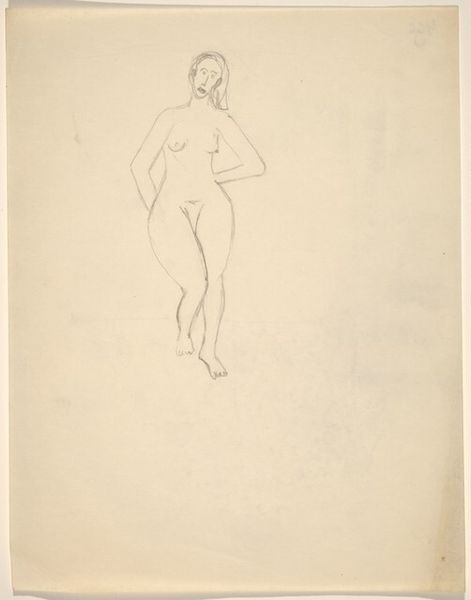

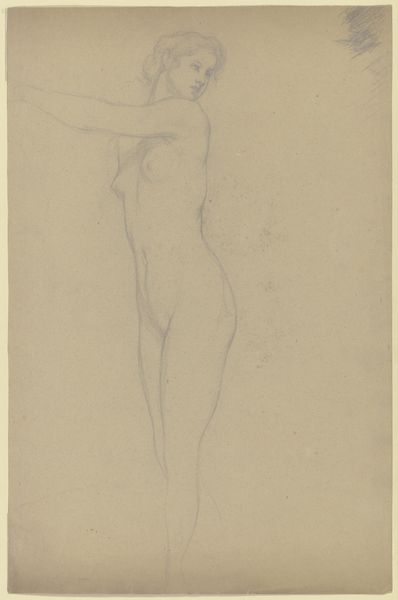

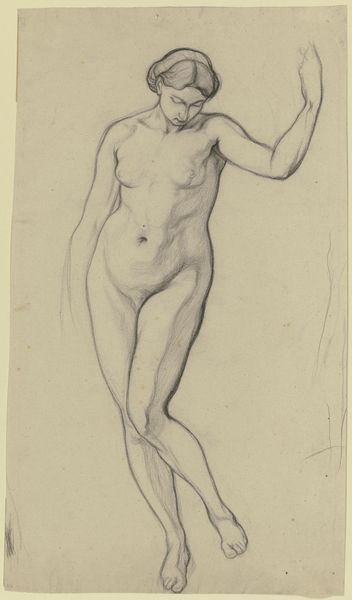

Stehende Frau als Aktfigur, aus _Ritter Hartmut von Kronberg bei dem Reformator Oecolampadius in Basel_ c. 1866 - 1867

0:00

0:00

drawing, paper, pencil, chalk

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

amateur sketch

#

toned paper

#

light pencil work

#

16_19th-century

#

pencil sketch

#

figuration

#

paper

#

personal sketchbook

#

german

#

pencil drawing

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

pencil

#

chalk

#

sketchbook drawing

#

portrait drawing

#

pencil work

#

academic-art

#

nude

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Here we have "Stehende Frau als Aktfigur, aus _Ritter Hartmut von Kronberg bei dem Reformator Oecolampadius in Basel_," a pencil and chalk drawing on toned paper, dating to around 1866-1867, by Victor Müller. It's currently housed here at the Städel Museum. Editor: My initial impression is that this has an almost fragile quality. It’s delicate and feels very much like a fleeting moment captured from life, or maybe from the artist’s imagination. Curator: Absolutely, and the context is fascinating. Müller was deeply engaged in history painting and religious narratives. Considering the setting within the larger project about the Reformation, this figure, even as a nude study, can be read in relation to power, transgression, and representation of the female body within religious history. The female nude becomes a site where historical and contemporary discourses intersect. Editor: It strikes me how immediate it feels. It looks like an exercise in the mastery of the human form, stripped bare. I'm thinking about the types of pencils and paper available to Müller at that moment. It brings the artistic process into focus, thinking about the materiality. What kind of chalk was he using, where was the paper made? What type of workshop practice was this? Curator: That focus on the materials and labor helps ground the interpretation. We have to consider Müller's relationship with academic traditions and how his identity as a German artist within 19th century discourse played out in choices of the body and subject matter, especially because he chose to put it within a religiously significant project. How might ideas around nationalism and representations of ideal beauty have been at play here? Editor: I also think the ‘unfinished’ feel speaks to a certain artistic freedom that came from sketch work and experiments, pushing against the strictures of traditional academic painting. The toned paper and varied pressure of the pencil—these elements, simple as they are, show Müller engaging directly with his medium. This process creates immediacy. Curator: Ultimately, it’s a study that allows us to ponder Victorian Germany’s relationship to its religious past, but also reflect on how even sketches can carry deep social and historical weight regarding body politics and artistic practices. Editor: Yes, and by focusing on these specific, material conditions and decisions, we are left not just with a figure, but with a deeper knowledge of art’s complicated social landscape.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.