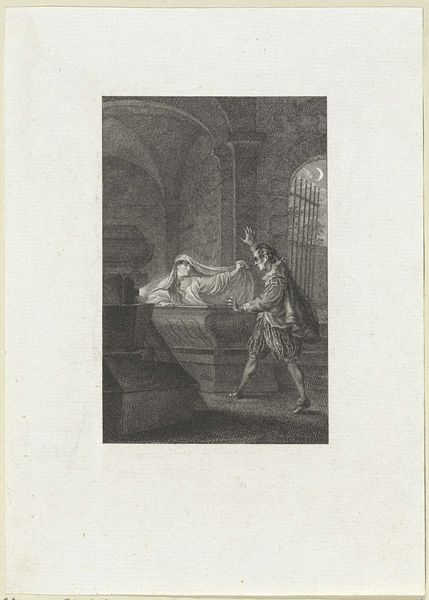

Dimensions: height 145 mm, width 83 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

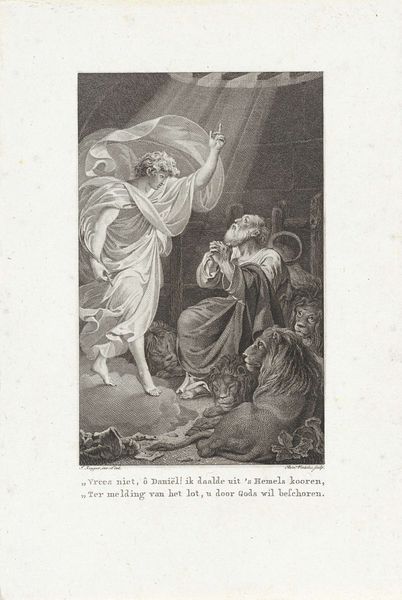

Curator: This is Reinier Vinkeles’ “Night View with a Man Holding a Dead Woman on His Lap,” created in 1769. It’s currently held at the Rijksmuseum, and done in engraving, pen and ink. Quite a dramatic scene unfolds. Editor: It certainly is. The high contrast immediately grabs your attention. The sharp light focusing on the man’s anguished face and the woman’s pallid features creates a real sense of heightened emotion. Curator: The romanticist drama is so rich, don’t you think? Note the iconography of grief and despair – the collapsed body of the woman, contrasting against the dynamic, expressive stance of the man, not to mention the bleak setting… Even the background architecture seems to oppress them. It creates this atmosphere of psychological distress. Editor: It really highlights the social role that art played during that time – as a mirror reflecting society's understanding and acceptance of profound emotions, almost a performative display of grief that conformed to the Romantic ideal of expressing strong feelings in public and the artifice surrounding that concept. Do you think that changes the narrative here, though, looking at that romantic lens as artificial rather than 'real'? Curator: In truth, every lens changes the story, that's what is wonderful and horrifying about human-made works such as this one! However, given Vinkeles’ stylistic choice of mannerism I find his Romantic art speaks more as a kind of language – using visual and cultural shorthands to communicate deeply-felt sentiment in a universally understood symbolic way. Editor: But doesn't the manipulation of that language shape the emotional content, influencing the viewer toward specific pre-scripted feeling states that conform to cultural norms, though? Is the art then just dictating appropriate ways to grieve? Curator: Not dictating, exactly! The visual language becomes a medium for catharsis, an agreed-upon format where deep emotions can be processed and even shared, rather than strictly confined. Editor: Fair enough. Maybe this work encapsulates an agreement, the start of dialogue between artist, subject, and viewer using a cultural and iconographical script. It reveals quite a bit about how eighteenth-century society grappled with emotion, and how we continue to do so now. Curator: A dance with grief, captured through ink and paper. So powerful how visual culture preserves echoes of past emotional dialogues that still resound today!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.