drawing, watercolor

#

drawing

#

landscape

#

perspective

#

charcoal drawing

#

watercolor

#

romanticism

#

cityscape

#

history-painting

#

watercolor

#

monochrome

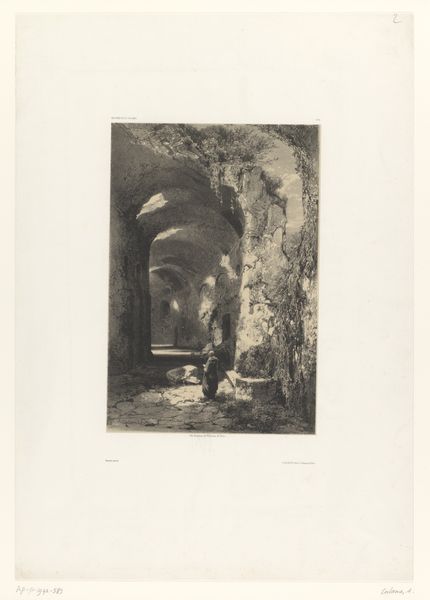

Dimensions: height 493 mm, width 376 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

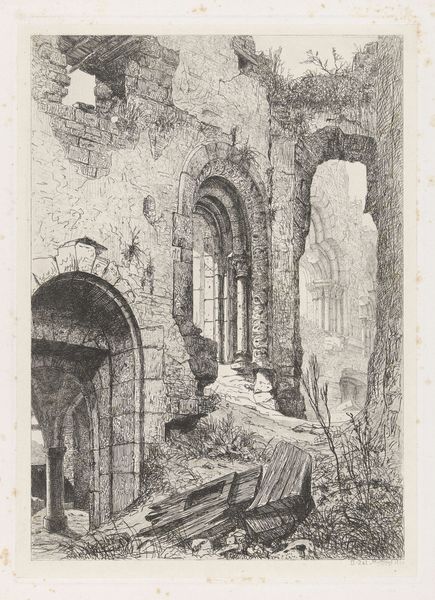

Curator: It is a rather bleak scene. What emotions rise to the surface as you take it in? Editor: Melancholy, certainly. There’s a tangible sense of ruin, loss of something grand, all rendered in almost sepia tones… It feels like history’s weight is crushing the scene. Curator: Indeed. We are looking at Gerard van Nijmegen’s, "View in a Ruin (Brederode?)" made with watercolor and charcoal drawing around 1794. This work presents what is most likely a perspective view from within the ruined castle of Brederode. It invites meditation on transience and the sublime. Editor: It’s interesting how these ruinscapes were often presented during periods of political upheaval, specifically in the wake of revolution. The crumbled archways, the scattered debris, all mirror society's vulnerabilities, especially systems of power that become eroded. Curator: Absolutely. Notice how the arches and repeating structure work. Ruins become more than just physical spaces; they turn into symbols of past ages, embodiments of collective memory, resonating with both grief and perhaps a cautious hope for renewal. The artist presents them as an integral aspect of human progress, serving as lessons of a kind. Editor: Yes, the play of light and shadow casts a particularly Romantic aura on the whole composition, framing the architecture. This wasn't just about documenting the landscape—it was a potent visual metaphor that challenged viewers to confront uncomfortable truths about human nature. It's important to remember that monuments aren't apolitical. Their presence asserts dominance. Their ruins? Defiance. Curator: This specific example is haunting, inviting the eye toward figures near the horizon line; they are reminders that humanity endures and survives beyond the crumbling walls of castles. Van Nijmegen presents us with more than history, doesn’t he? Editor: Ultimately, it underscores that history is dynamic. This artwork isn’t frozen in time; its implications for the current landscape still linger. Perhaps we should spend more time thinking of ways we are doomed to repeat it… Curator: Or perhaps not, focusing on ruins’ potential to be sites of reconstruction.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.