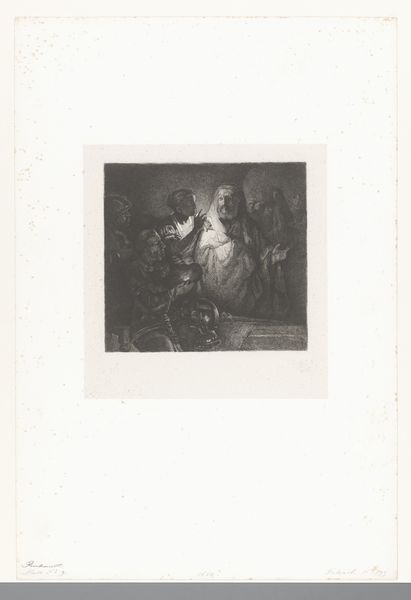

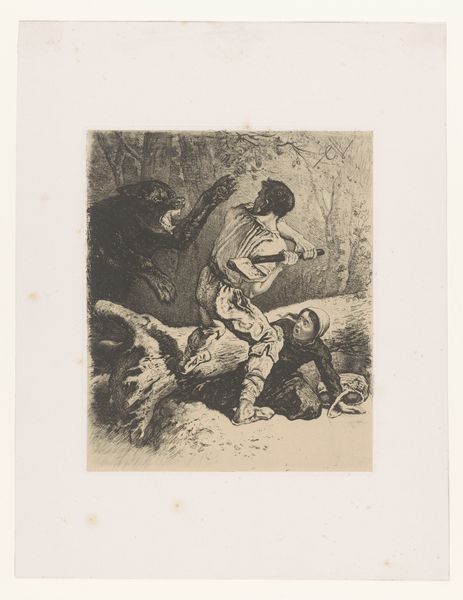

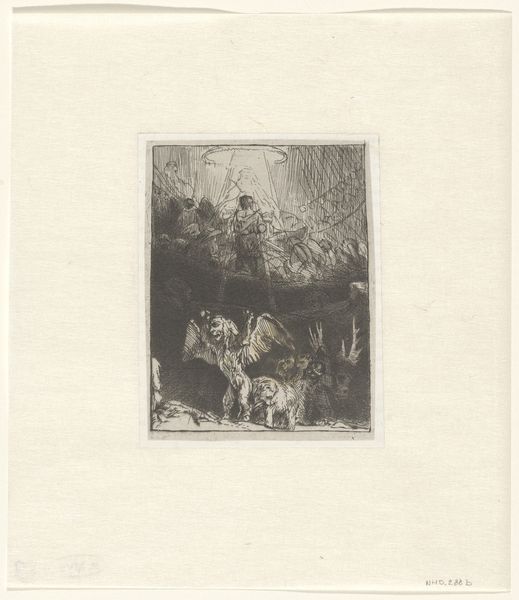

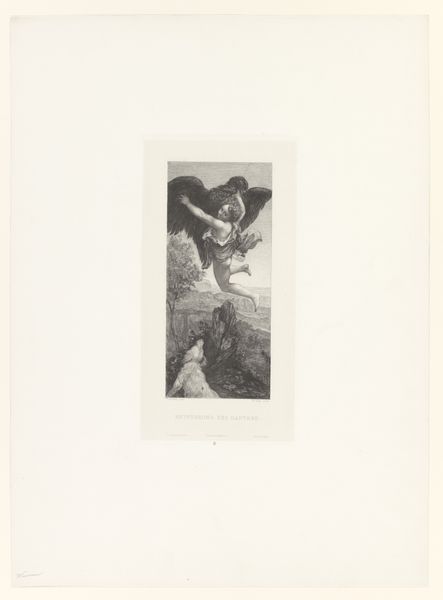

Engel weerhoudt Abraham ervan zijn zoon Isaak te offeren 1857 - 1914

0:00

0:00

print, engraving

#

narrative-art

# print

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 251 mm, width 187 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: What strikes me immediately is the almost suffocating density of the engraving, creating a powerful dramatic tension. The lines are so close together. Editor: Indeed, it really heightens the gravity of the situation. This engraving captures the biblical scene of "Engel weerhoudt Abraham ervan zijn zoon Isaak te offeren" ("Angel Preventing Abraham from Sacrificing his Son Isaac"), dating roughly between 1857 and 1914, made by Nikolay Semyonovich Mosolov. You see the dramatic intervention right at the climax of the story. Curator: And the visual hierarchy reinforces a top-down power structure – heaven quite literally intervening. Think about the period and what was sanctioned by the church and considered acceptable narratives! The angel descending feels less like salvation and more like… enforcement of order? Editor: That's a potent reading, really emphasizing the themes of divine authority, perhaps even a critique depending on the sociopolitical mood when it was made. The question of patriarchy looms large, right? The father is poised to sacrifice the son. The image makes us reckon with blind obedience, particularly for young, often queer and non-binary viewers. Curator: Yes, how that demand for unquestioning obedience is depicted visually! Notice the lack of detail in Isaac's face compared to the very detailed visage of Abraham. Isaac appears as a kind of symbolic object or vessel for carrying out God's request of Abraham. His lack of power renders the scene agonizing to view. Editor: It hits on this problematic tradition of generational trauma. Here, Isaac is saved at the last moment, but how many other vulnerable bodies are never saved because they exist outside of established institutional hierarchies of power, recognition, and rescue? What responsibility do religious institutions bear in protecting such groups from symbolic or literal harm? Curator: Precisely, these engravings offer a potent reminder of how deeply religious narratives permeate even secular society, continually shaping our understanding of power, sacrifice, and salvation. What stories are perpetuated and by whom? These questions can help to contextualize what it means to believe something versus simply understanding the stories being told about those beliefs. Editor: Looking at art this way, we’re really confronting our histories, personal and collective. Thank you for offering that critical lens through which we can reexamine and reimagine our connections to these classical scenes.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.