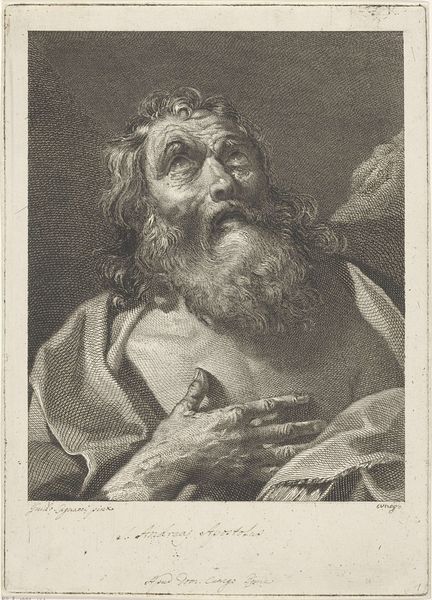

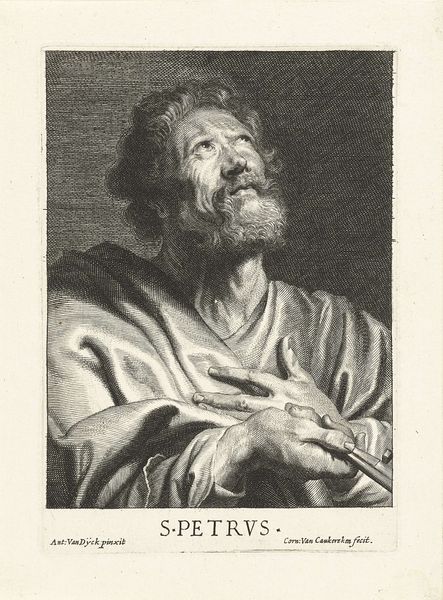

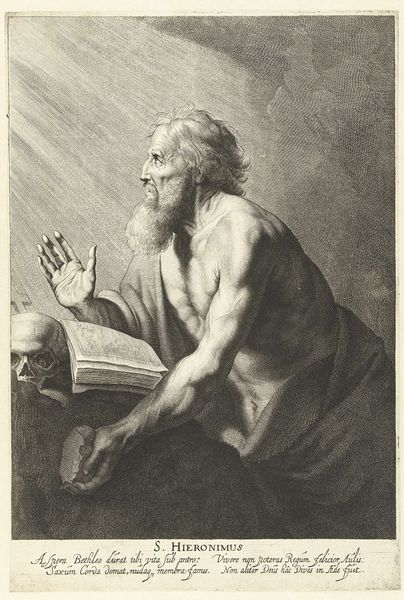

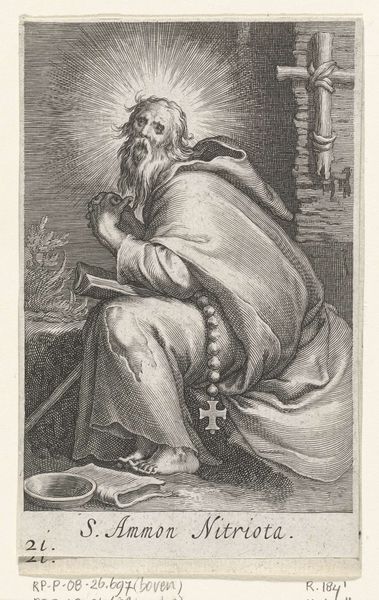

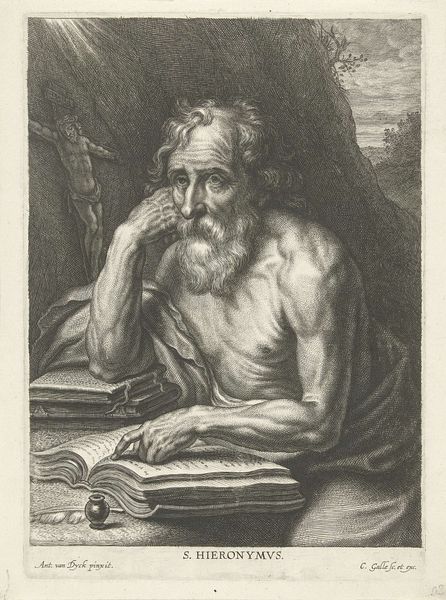

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

portrait reference

#

animal drawing portrait

#

portrait drawing

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 170 mm, width 117 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is "Simon," an engraving from around 1640 to 1680, attributed to Cornelis van Caukercken, housed in the Rijksmuseum. It’s a striking portrait; there's such intense detail in the rendering of his face and the drapery. How do you interpret this work, particularly within its historical context? Curator: Well, immediately I’m drawn to the depiction of Simon and the potential power dynamics embedded in its creation. The print, though credited to Caukercken, is "after" Anthony van Dyck. Who was Simon to van Dyck, and by extension, to Caukercken who reproduces his image? Was he a biblical figure, a member of the upper class, or perhaps even someone from a marginalized community? The sitter's identity and social positioning are really crucial. Editor: That's interesting. I hadn't considered the social implications. So, you're saying the act of representation itself could reflect power imbalances? Curator: Precisely. During this era, portraiture wasn't just about capturing a likeness; it was about asserting status, constructing identity, and controlling narrative. Consider the gaze, the setting, even the textures achieved through the engraving process—all these elements communicate meaning. And who had the power to commission or control such images? Whose stories were being told, and whose were being erased? Editor: So, analyzing this engraving means thinking about not only the technical skill but also the social and political context that made it possible? Curator: Absolutely. By examining "Simon" through the lens of identity and power, we can unpack broader narratives about class, representation, and the complex relationship between artist, sitter, and audience in the 17th century. Editor: That’s given me a lot to think about. It’s much more than just a portrait—it's a social artifact. Curator: Indeed. Hopefully, this sheds light on understanding visual culture as a dialogue rooted in socio-historical conditions, opening conversations of race, gender, and class.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.