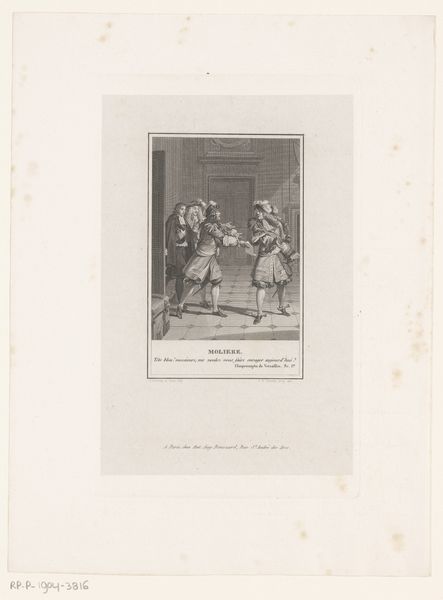

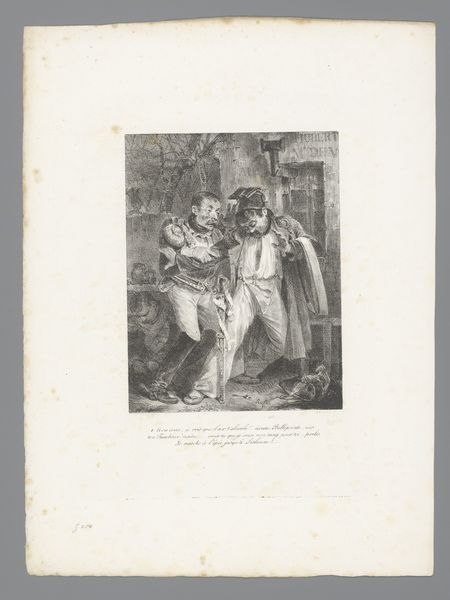

drawing, print, etching, ink, engraving

#

drawing

# print

#

etching

#

ink

#

history-painting

#

engraving

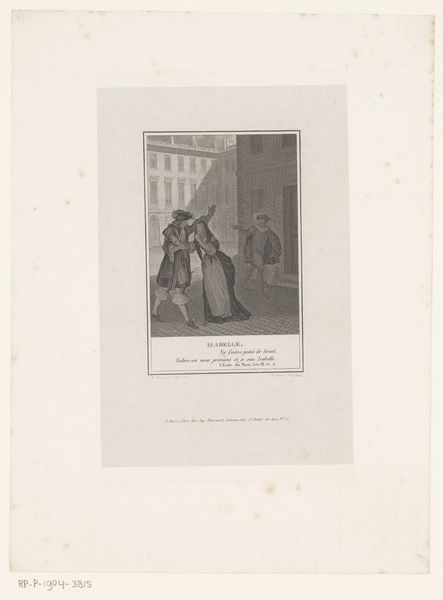

Dimensions: Sheet: 9 1/16 × 6 11/16 in. (23 × 17 cm) Image: 4 3/8 × 3 1/4 in. (11.1 × 8.3 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

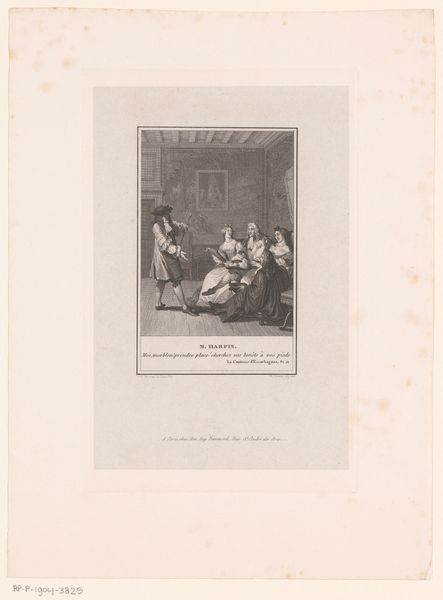

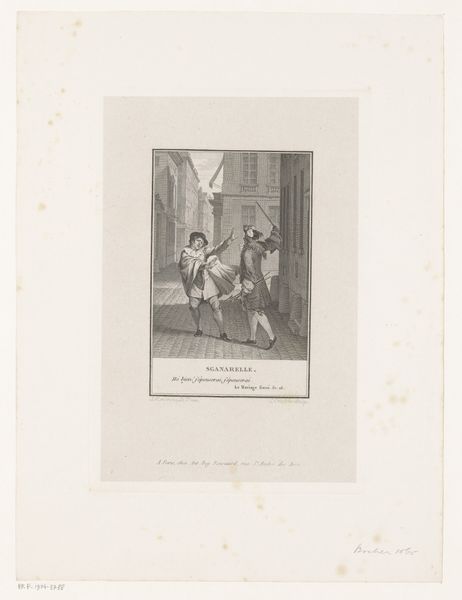

Curator: This is Horace Vernet’s "Monsieur Jourdain," an etching and engraving in ink from sometime between 1835 and 1845, depicting a scene, presumably, from Molière’s "Le Bourgeois Gentilhomme". Editor: Yes, the print has an interesting almost theatrical energy. I see a clash between two figures and a supporting cast in the background. How do we even begin to analyze something like this? Curator: We could start by considering the material conditions that made such prints possible. Etchings and engravings were not only artistic expressions but also commodities produced and consumed within a particular social and economic context. Editor: Commodities? So, like a product churned out on an assembly line? Curator: Not exactly, but think about the division of labor involved. Someone had to create the initial design, another might have executed the etching, and then you have printers making multiple copies. These processes speak to evolving ideas of artistic production in the 19th century. This brings the possibility of a much broader audience beyond the traditional elite that consumes fine art. How might that shift impact the subject matter of art? Editor: Good point, with Molière's comedy. It seems that plays targeting social hierarchies, through prints and theatrical performances, are now for popular consumption? What would you say are the economic conditions that facilitate all this? Curator: The rise of a wealthier middle class, advancements in printing technology and distribution, and an increasing desire for accessible cultural products... consider how these prints were sold, framed, displayed in homes – these material considerations reflect and shape the art itself. The etching becomes accessible because it's a cheaper material to produce, in turn enabling mass consumption of art. Editor: Fascinating! So it's less about the high-minded ideas and more about the who, what, when, where, and how this object came into being. Thanks for opening my eyes to these new aspects. Curator: Exactly. Thinking materially can reveal hidden narratives and power structures embedded within even the seemingly straightforward image. It prompts a much broader scope for historical background beyond the artist's creative inspiration.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.