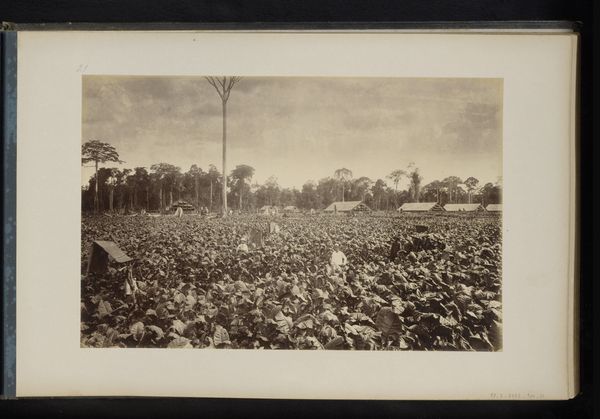

print, photography

# print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

orientalism

#

genre-painting

#

post-impressionism

Dimensions: height 89 mm, width 179 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

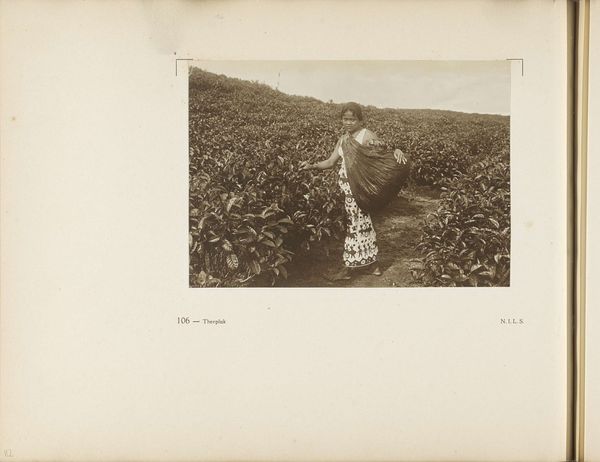

Curator: This is titled "Veldarbeiders op een theeplantage op Java," or "Field Workers on a Tea Plantation in Java," taken in 1902, presumably as a stereograph. The artist is Carleton Harlow Graves. Editor: The first thing that strikes me is the starkness of the image. It is primarily monochrome and, beyond the workers themselves, emphasizes the density of the tea bushes and the repetitive patterns of labor. Curator: Absolutely, that repetitive element is key. Let's consider this through the lens of labor exploitation during the colonial period. This image romanticizes the work. What this photograph elides is that those fields, and therefore, the labor extracted, were for the consumption of Europeans, built on stolen land. This becomes crucial to any modern understanding of exploitation and identity under colonialism. Editor: And consider the sheer labor involved in its production: the planting, cultivating, and then the photographing and reproduction of images like this. Each stage of the process speaks to the social organization of production within the plantation system, a direct extraction of resources. This image isn't simply a representation of a landscape, but a record of intensive manual effort. Curator: The depiction of the workers contributes, I believe, to that same kind of colonial gaze, placing the native workers in a subservient, exoticized role within their own land. These visuals have historically perpetuated distorted narratives of power, contributing to the erasure of their agency. The framing perpetuates that specific type of cultural insensitivity. Editor: Right. And what's further disturbing is considering who this stereograph was designed for. Mass consumption? What would viewers at that time in history have considered it to mean, in light of global politics? That is embedded in the materiality itself of such works of art, not simply the political framing that’s involved in the work’s distribution. Curator: Looking at this photograph is to dive deep into these discussions about labor, commodification, colonialism, identity, and exploitation—a past whose effects very much linger in contemporary power dynamics. Editor: Yes, recognizing those tangible links between artistic output, labor practices, and socio-economic histories empowers a much richer, and I would add responsible, understanding of such a scene.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.