Copyright: Public domain

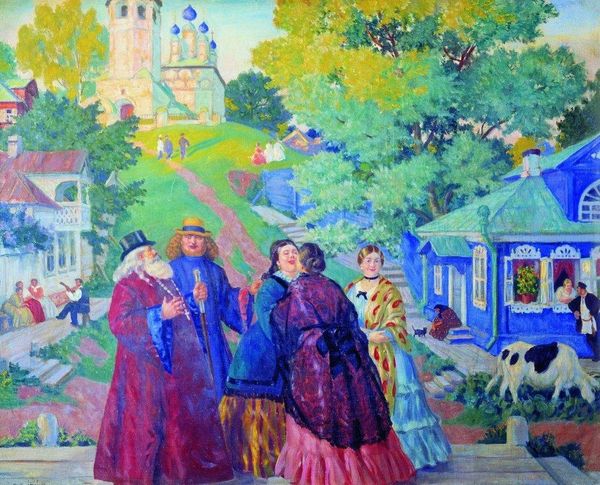

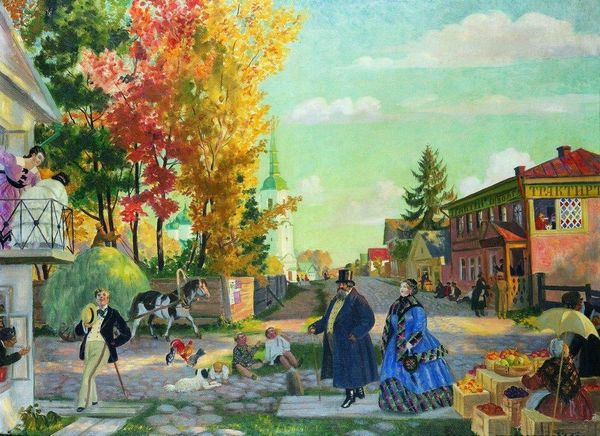

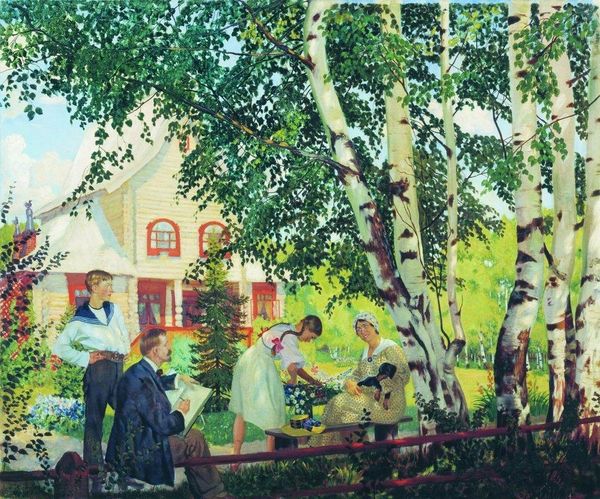

Curator: This is Boris Kustodiev's "Merchant's Wife on the Promenade," painted in 1920, offering a glimpse into a Russia undergoing profound social and political transformation. Editor: My first impression is one of theatricality; the figure is monumental, but the colors, while bright, also feel somewhat…muted, almost as if faded by time, a kind of dream. Curator: Indeed. Kustodiev positions her not simply as a portrait, but as a symbol. Her attire and bearing represent a specific class at a pivotal juncture. The choice of bright colors against the backdrop of what looks like a Russian village highlights the contrasts inherent in Russian society. It also offers a stark look at the patriarchal setting in which women occupied roles heavily defined by class. Editor: Note the artist’s specific choices in materials and application: oil paint, of course, which gives the painting that wonderful, palpable texture. But consider how he builds up those textures on the fabrics and also the somewhat naive manner of execution, almost like folk art, despite the sophistication of the overall composition. What does it tell us about how such works might function for the intended viewer? Curator: The painting becomes a stage upon which questions of identity and power are negotiated. She isn’t simply a wealthy woman, but represents, simultaneously, the excesses and vulnerabilities of a system in flux. There’s tension in that contrast, between the bright exterior and the sense of precarity in post-revolutionary Russia. The perspective emphasizes that it’s an oil on canvas but meant for visual interpretation like folk and applied art. Editor: It's fascinating how Kustodiev’s process, employing what one might call naive painting techniques, elevates a single figure to represent something larger, while simultaneously reminding the viewer of the materiality of the artwork itself—the very physical presence of paint and canvas being crafted and consumed. Curator: Right, and considering Kustodiev’s own physical struggles—he was confined to a wheelchair for much of his later life—adds another layer. There is then something undeniably powerful in his rendering of a life—ostensibly a good life, at least a wealthy one—rooted in materiality and visible prosperity, yet framed by societal change, his individual situation, too. Editor: I appreciate seeing how focusing on the materials and methods Kustodiev employs complicates the picture; he turns oil and canvas into a commentary on Russian social structures. Curator: And through that, allows us a poignant reflection on identity during turbulent times.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.