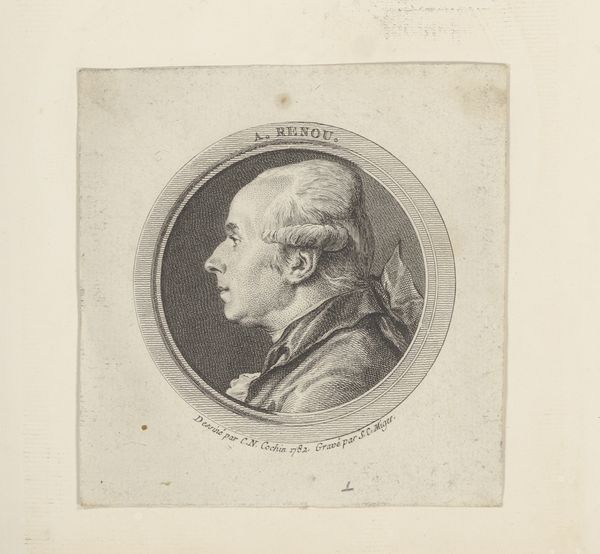

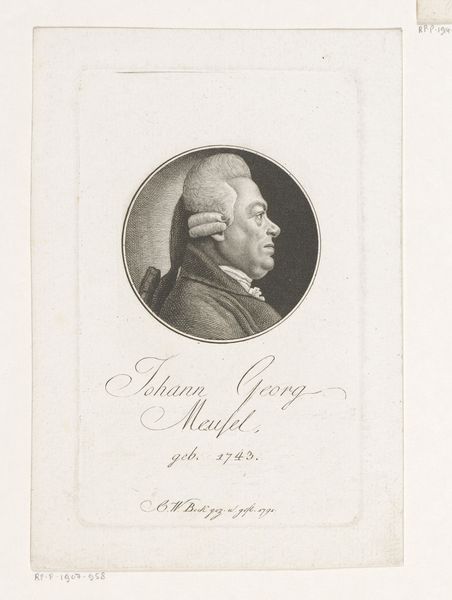

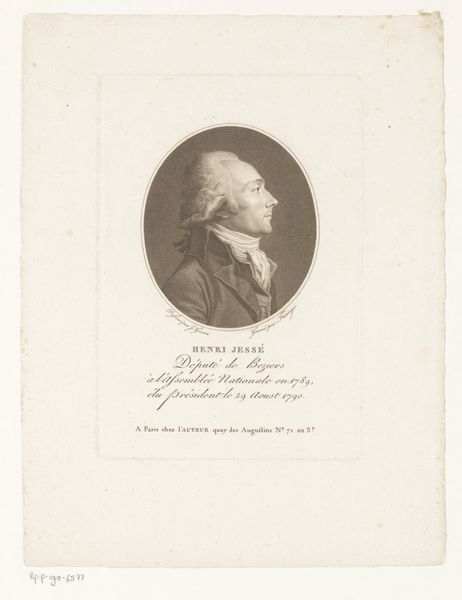

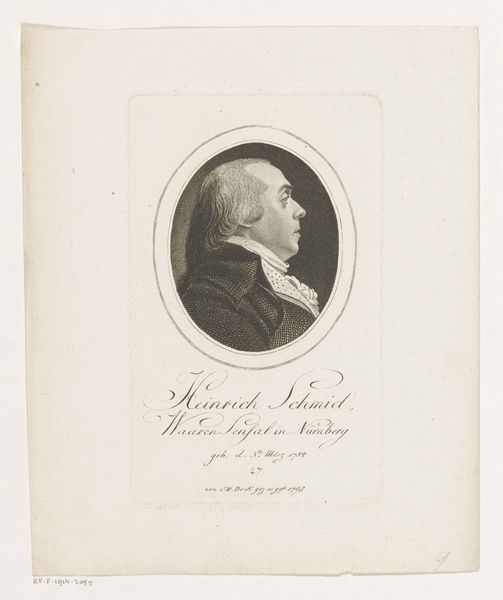

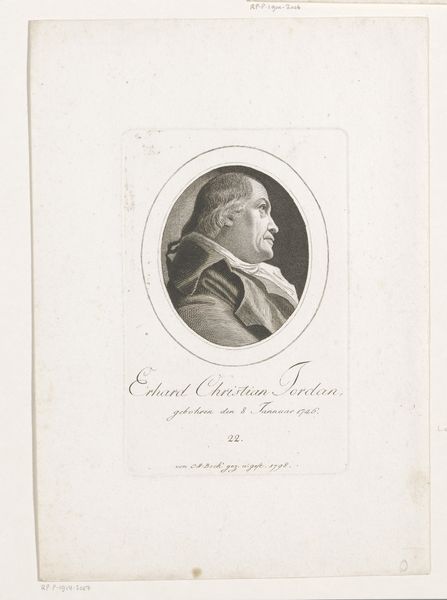

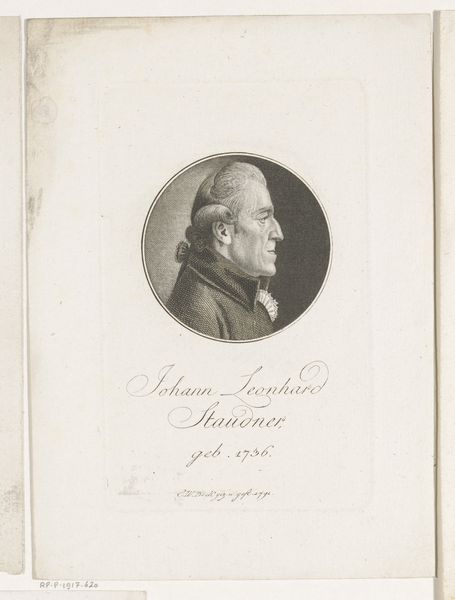

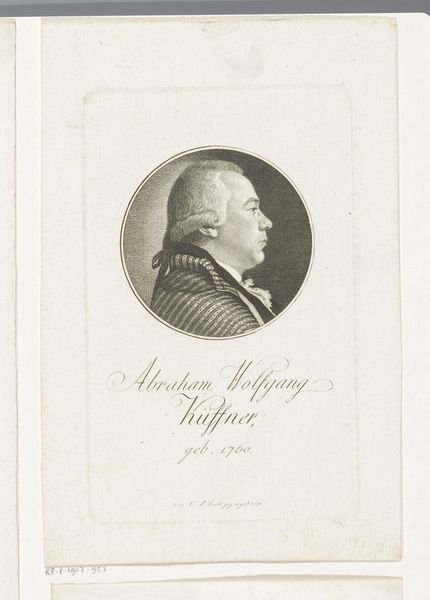

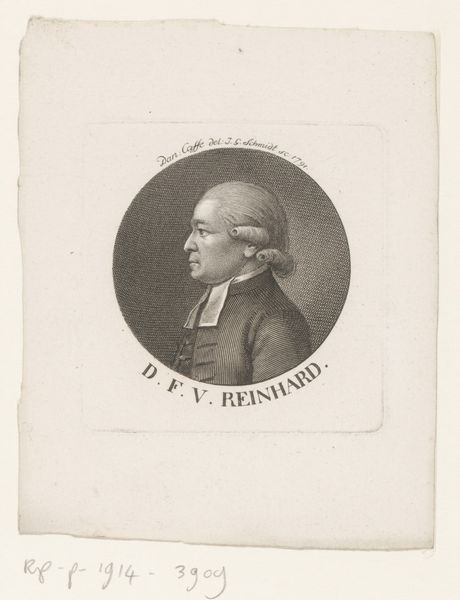

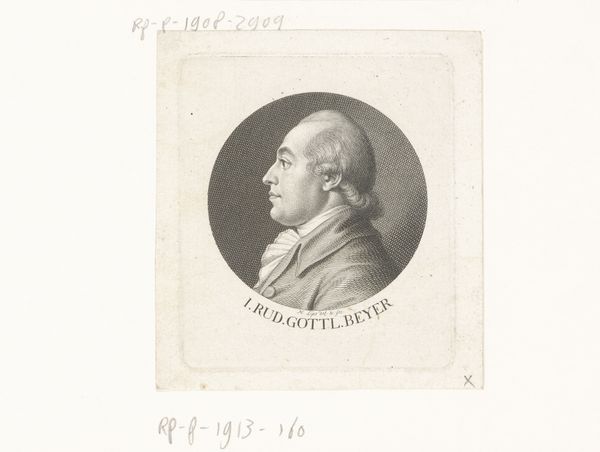

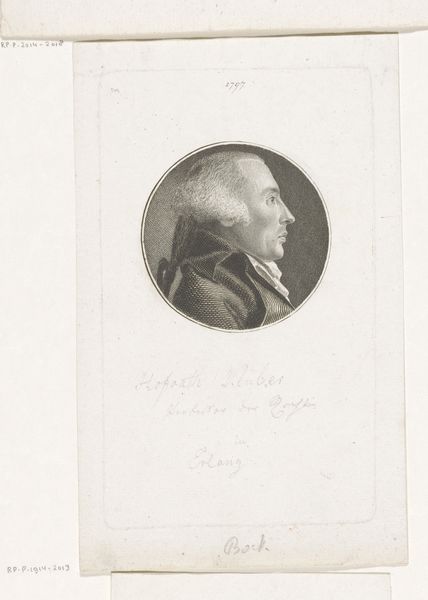

drawing, print, engraving

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

#

aged paper

# print

#

pencil sketch

#

old engraving style

#

pencil work

#

engraving

#

historical font

Dimensions: height 148 mm, width 92 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Christoph-Wilhelm Bock’s “Portret van Simon Auguste André David Tissot” from 1791. It's an engraving. I’m struck by its formal, almost austere presentation, but also the skill involved in creating such detail with what seems like simple lines. What stands out to you about this portrait? Curator: Considering its historical context, this engraving performs significant cultural work. It's not just an image; it's a statement about status and the construction of identity in the late 18th century. Bock created a replicable image for public consumption. Editor: So, this was meant to circulate, beyond just being a personal keepsake? Curator: Precisely. Engravings were a means of disseminating images widely, shaping public perception. Tissot, clearly a man of standing, is presented in a manner befitting his status. This carefully constructed image reinforces a particular social hierarchy, wouldn't you agree? What do you make of the text beneath the image? Editor: I notice the Roman numerals indicating his birth year, MDCCXXVIII, and a death date. That font feels like it echoes the formality of the portrait itself, almost like an official record. So it almost reinforces his importance? Curator: Absolutely. The careful lettering, the formal attire, the choice of engraving – all these elements contribute to constructing Tissot's public persona and cementing his place within a particular social order. Images like these played a crucial role in how individuals and institutions presented themselves. Did this portrait challenge your notions of art as personal expression? Editor: It did. I was initially drawn to the artistic technique, but seeing it as a tool for social and political messaging makes it even more compelling. Curator: Precisely, and that’s the power of understanding art within its historical framework.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.