Dimensions: height 356 mm, width 260 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

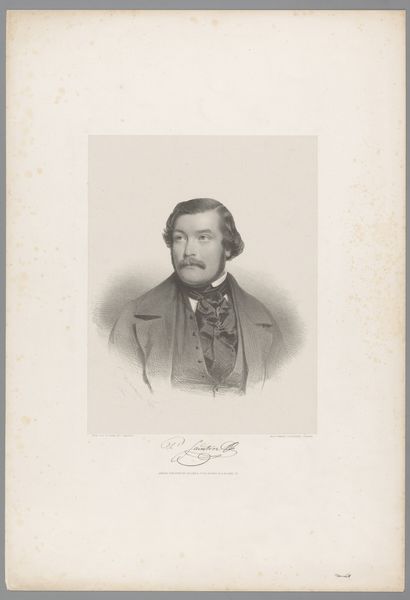

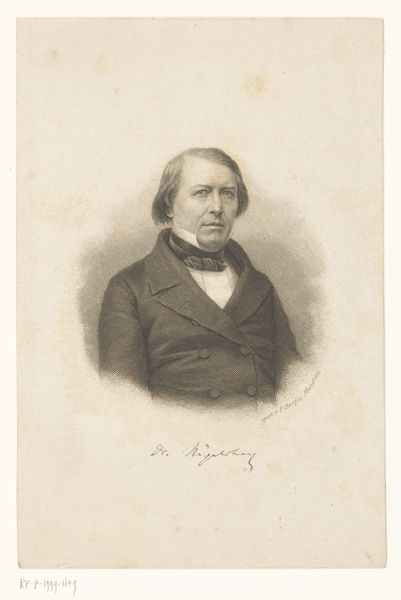

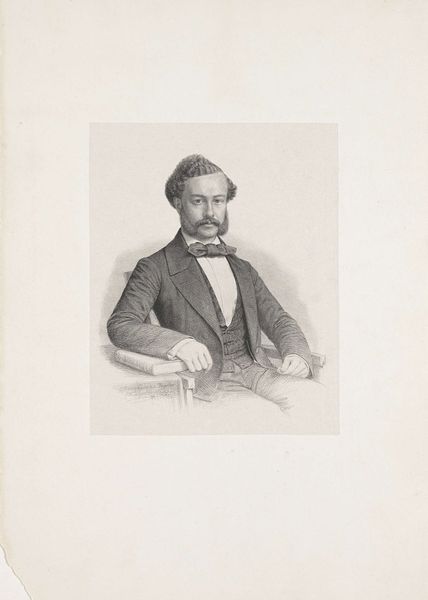

Curator: Before us hangs Franciscus Bernardus Waanders's pencil drawing, "Portret van Hendrik Conscience," likely created between 1847 and 1865. Editor: It’s remarkable how much texture and detail he achieves with just pencil. It gives off this very reserved, dignified air, wouldn't you agree? A certain stoicism in his gaze. Curator: Absolutely. The materiality of pencil allows for incredible control over light and shadow. Waanders seems fascinated by the layered application—hatching, cross-hatching to build form, the softness, contrasted with sharply defined lines for his suit. He uses the simplest materials to produce a sign of elevated class standing. Editor: That calculated contrast also speaks volumes about societal expectations then. Conscience, ornamented with medals, projects the image of established power, reflecting nineteenth-century ideas surrounding national identity and achievements. This image surely was part of nation-building processes. It evokes that romantic hero archetype so tied to early nationalism. Curator: His position is intriguing when you consider the availability of cheap, printed reproductions around this time. Who was consuming this image, and how did its handmade quality factor into the work’s reception? We can also reflect on what labour was considered and given value at that point in history, thinking through our modern definitions around both labor and value creation. Editor: And isn't it fascinating to consider who Conscience actually was – a Flemish writer vital in creating a cultural and national identity? How that identity perhaps implicitly reinforces dominant social structures or gender norms? Curator: Examining Waanders's skillful handling of pencil work alongside Conscience's symbolic weight enriches our comprehension of nineteenth-century aesthetics, labour and modes of production. Editor: Agreed; I find thinking about his art in light of questions around visibility, nationalism and power to be profoundly insightful. I come away with an expanded vision for interpreting not only the past, but the role imagery takes today.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.