#

hand-lettering

#

playful lettering

#

hand drawn type

#

hand lettering

#

flower

#

personal sketchbook

#

hand-drawn typeface

#

fading type

#

plant

#

sketchbook drawing

#

botany

#

sketchbook art

#

small lettering

Copyright: Public domain

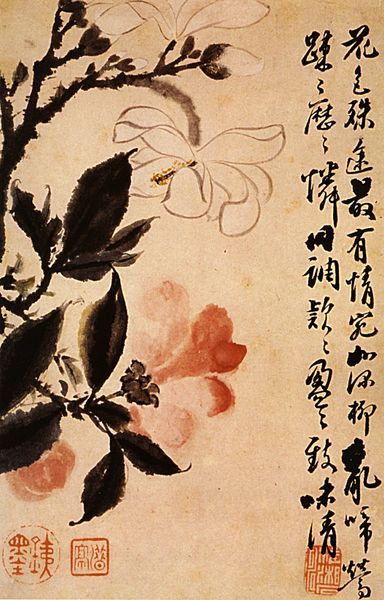

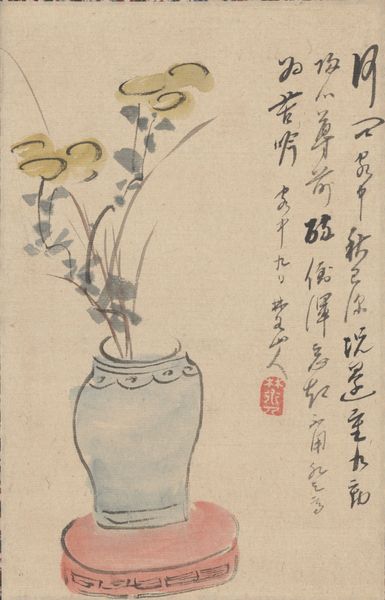

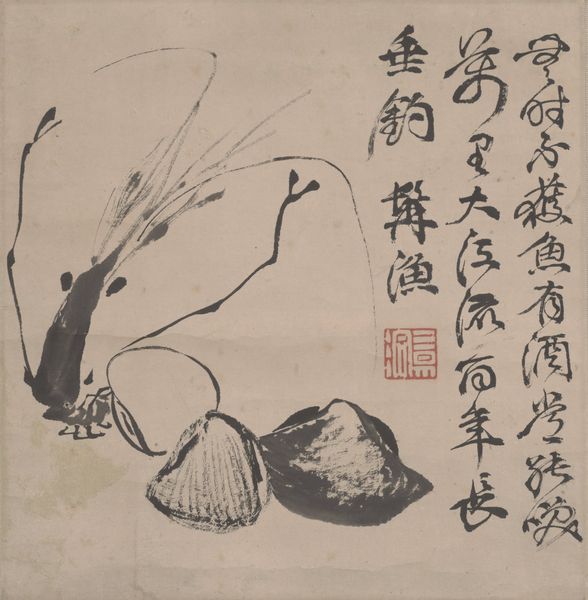

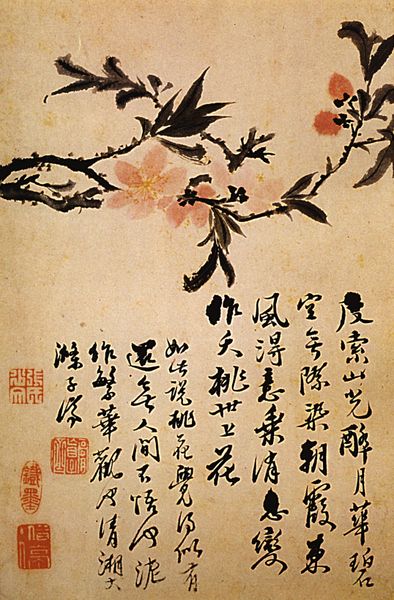

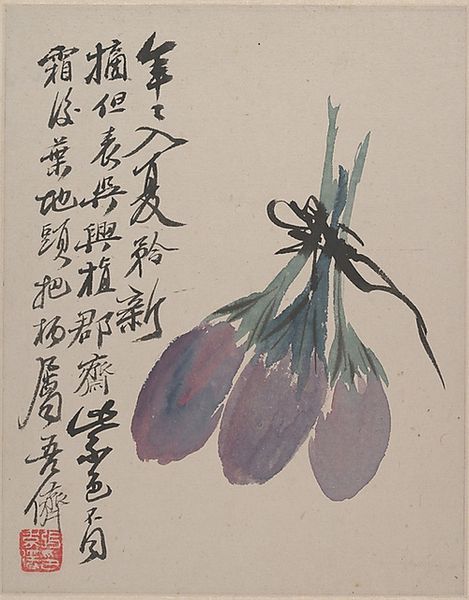

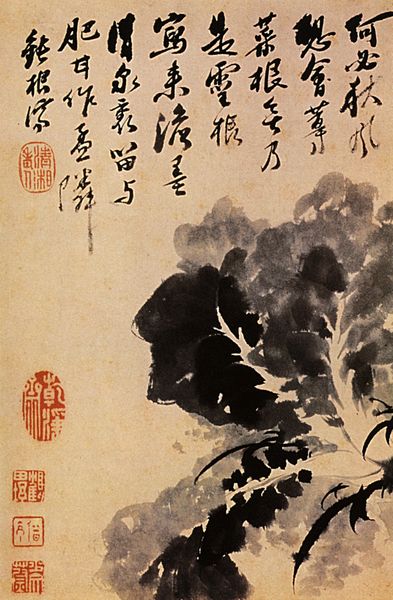

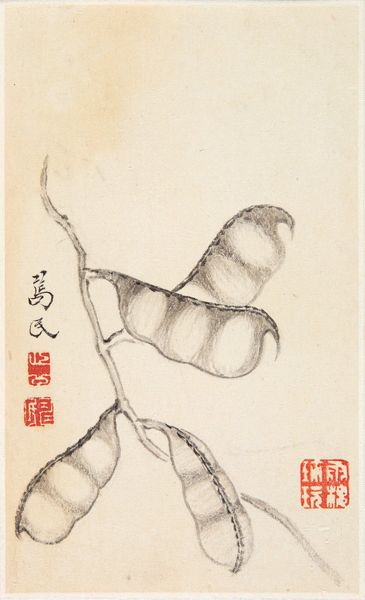

Curator: Shitao's "The Melons," created in 1707, immediately strikes me as a work of profound aesthetic balance. The restrained palette, the economy of line—it’s all rather elegant. Editor: Restrained maybe, but the gaze wanders. The social unrest that marked Shitao's era deeply resonates here. A lone scholar turning to still life isn’t apolitical; it’s a conscious retreat from a fractured court and cultural landscape. Curator: Fractured indeed, but the interplay of dark ink washes creating the leaves against the lighter fruit and the elegant calligraphic inscription form a beautiful visual rhythm. Note how the shapes create positive and negative space, directing the eye. Editor: That visual rhythm is further complicated when we acknowledge the text included which are full of complex ideas. Each line alludes to broader concepts—the fleeting nature of time, the solace found in simplicity—perhaps echoing the artist's conflicted position within society. These persimmons as a meditation rather than simply an illustration. Curator: True, yet let’s not overlook Shitao’s technique. He employs the “boneless” method, relying on ink washes rather than outlines, endowing the melons with a soft, almost ethereal quality. Observe too how different brushstrokes differentiate leaves, stems, and fruit, highlighting each with precision. Editor: The artist also has added their stamps and calligraphic comments with poetic references in what might be understood as both his "signature," yet at the same time is something very political in its expression within the social climate in the 1700's. Curator: Indeed. To me, "The Melons" displays formal restraint, revealing Shitao's mastery of composition. It's a piece of deceptive depth. Editor: Exactly. It's through this layering of meaning, combined with the circumstances surrounding its creation, that a seemingly simple still life achieves an unexpected, potent complexity.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.