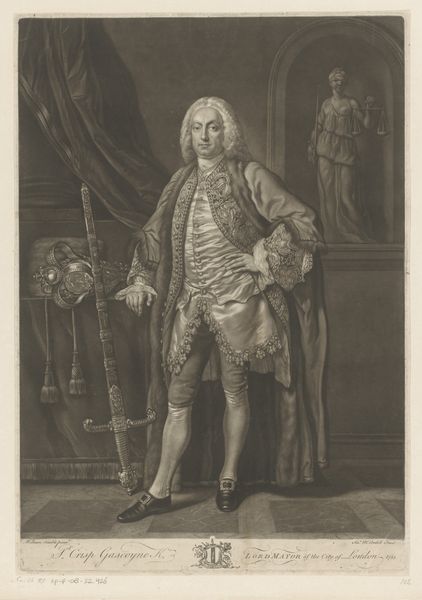

Portret van koning Frederik Willem I van Pruisen, keurvorst van Brandenburg 1687 - 1743

0:00

0:00

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 333 mm, width 213 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Johann Georg Mentzel's "Portret van koning Frederik Willem I van Pruisen, keurvorst van Brandenburg," an engraving that was worked on between 1687 and 1743. I'm struck by the density of the lines, all those tiny marks creating texture and form. What’s your read on this, in terms of material and process? Curator: I am interested in understanding how this portrait engages with the economy of image production in the early 18th century. The engraving medium suggests a means of replicating and disseminating the image of King Frederick William. We need to ask: Who was the intended audience for such prints? Were these objects meant for elite consumption or wider circulation? The labour involved in producing this print—the skilled hand of the engraver, the infrastructure needed to print and distribute—also reflects specific class relations and social conditions of the time. How does this seemingly simple portrait of a ruler point to these intricate networks of labor and exchange? Editor: So it's not just about the King's image, but who had access to that image and how they got it. I hadn't thought about the role of the engraver like that. What was the significance of portraiture, materially speaking, back then? Curator: Precisely. Engravings like these helped solidify power not merely through depicting the King, but through embedding the image within a system of production and distribution. Each copy represents an expenditure of labor and resources, creating a material link between the ruler and his subjects. The scale of the print run, the cost of each impression, and even the paper it was printed on contribute to our understanding of the king's image-making strategy. We also should consider where and how these were consumed; framed on a wall in someone’s home? Tucked in a book? What implications arise? Editor: I see it now. The materiality of the print speaks volumes about power, access, and even propaganda in a pre-digital age. It is definitely not only a decorative element. Curator: Indeed, a reminder that every object embodies the conditions of its making.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.