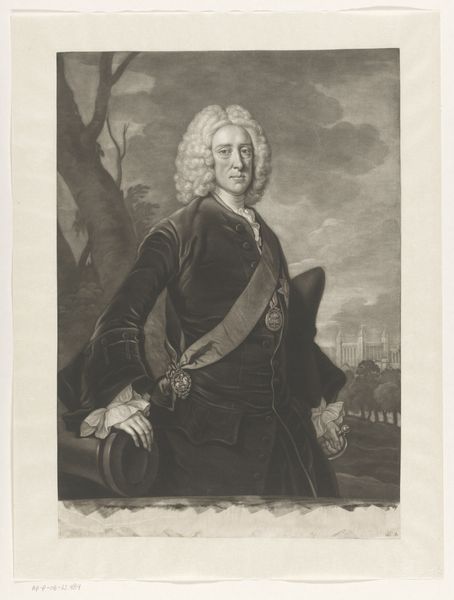

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

form

#

15_18th-century

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 503 mm, width 350 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Good morning, everyone. Today, we’re looking at James McArdell’s "Portret van Crisp Gascoyne", a print made sometime between 1753 and 1755. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: An imposing figure. Look at that robe, the wig, and what seems like a small, very impractical sword. There’s a rather starchy quality to the image. It feels quite distant and grand. Curator: Absolutely. McArdell worked with mezzotint engraving, allowing for a remarkable range of tones, giving the portrait an almost painterly feel despite being a print. Think about the skill involved in creating those gradients to describe silk, satin and velvet on his attire, not to mention the cold, hard steel of the sword. Editor: You can almost feel the texture. I am particularly fascinated by that juxtaposition of hard and soft materials, a very clear distinction being made with how metal sits alongside flowing, embroidered fabrics. There's so much material culture on display—the trappings of power are tangible. What about the backdrop? Curator: A draped curtain, almost stage-like, and behind, an alcove containing a statue of Justice. Typical allegorical accessories for formal portraits of the era meant to hint at the subject’s virtues. Still, McArdell had a knack for imbuing the faces he depicted with such subtle emotions. Do you get a sense of Crisp Gascoyne's personality from the print? Editor: Hmm. Perhaps a hint of weariness in the eyes, but also determination. This image clearly speaks volumes about class and the construction of public persona, almost like branding, wouldn’t you say? Gascoyne’s office demanded the accoutrements. Curator: Precisely! The image wasn’t just a likeness, it was a carefully constructed declaration of status, influence, and authority reproduced and distributed by printmaking technology, a means of multiplying presence. Editor: Which puts a very different spin on this man, on how he must have wanted the citizens of London to perceive him...It invites us to really consider who profited from the circulation of images like this—how class, capital and artistry intersected in 18th century London. I wonder if Gascoyne had any say in the construction of this portrait or was he at the artist's whim. Curator: These prints offer us a fascinating view of a historical figure—and perhaps the historical forces that created him. What about the process and its legacy? Did prints change people's perceptions of status? Editor: Ultimately, perhaps what strikes me most is the human labor behind such artifacts—both Gascoyne, an influential magistrate who sought public recognition, and McArdell, a gifted artist working to refine new printing techniques. It serves as a sobering reminder about how social identities continue to be crafted through materials, representation, and artistic production.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.