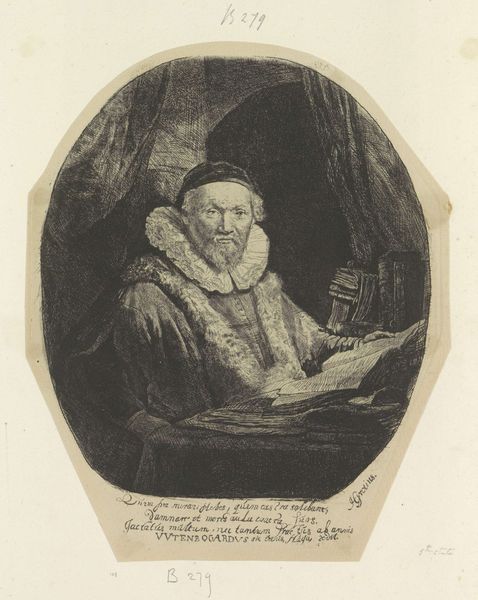

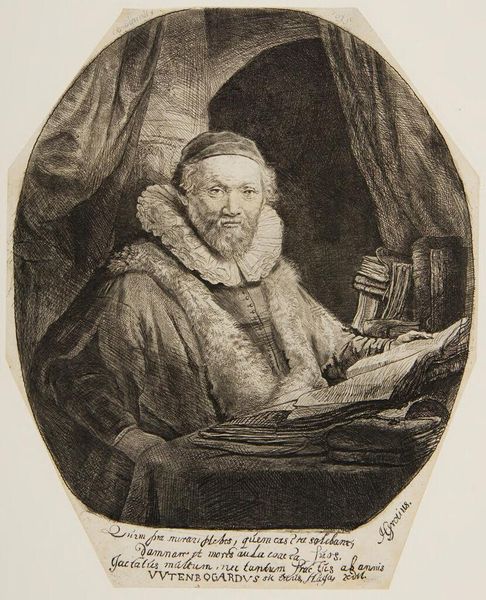

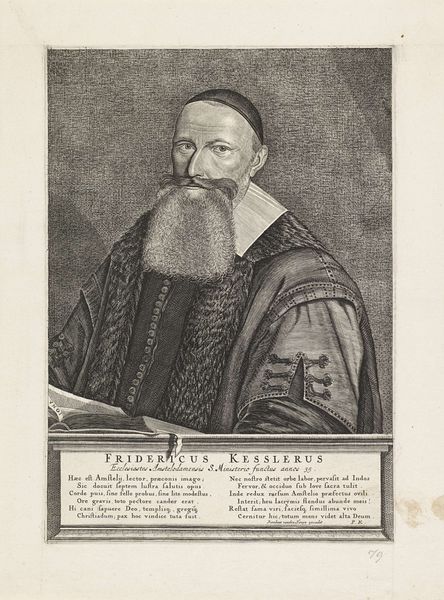

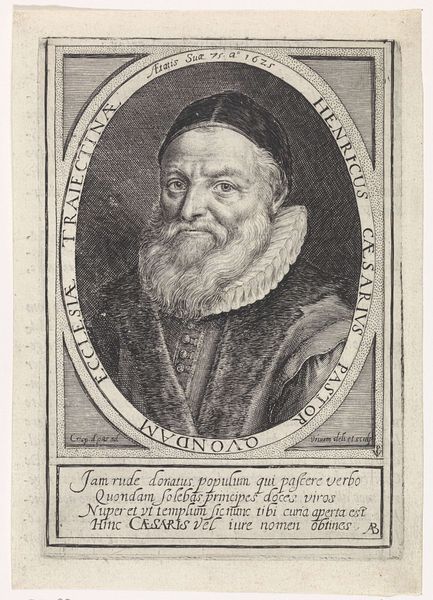

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 250 mm, width 183 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have Jacob van Loo's "Portret van Johannes Wtenbogaert," estimated to be made sometime between 1624 and 1670. It's an engraving, a type of print. My initial impression is one of quiet dignity. The oval format and monochrome palette lend a sense of formality and contemplation. Editor: The choice of engraving immediately speaks to its accessibility and purpose. Printmaking allowed for the wider dissemination of images and ideas; it served a specific function within the religious and political landscape. Let's consider how these decisions shape the meaning of the work. Curator: Wtenbogaert, a prominent Remonstrant leader, is depicted in scholarly garb, holding a book. His fur-lined coat and ruffled collar speak to his status, but his direct gaze feels very human and inviting. I read the books as a visual representation of Wtenbogaert’s intellect and faith. He has strong beliefs. Editor: Yes, the book is vital to decode the full story: what the print reveals about religious identity and authority. I'd focus on unpacking how Van Loo's print circulates specific ideologies through easily reproducible images—we need to ask: who was the target audience? This print operates within the networks of early modern media and belief. Curator: You're right, engravings made images and ideas widely available. It made artwork less costly and increased consumption for the bourgeoning middle classes of the Dutch Golden Age. It's a piece designed for widespread dissemination, a portrait meant to convey Wtenbogaert’s character and convictions beyond the elite. The engraving's lines are remarkably detailed—notice how textures are created? It demonstrates how labor goes into images that feel like common commodities. Editor: Exactly. Every element—the way Van Loo handles line, the very act of engraving as a method of reproduction—tells us something about the cultural values it aimed to perpetuate. This wasn't just a portrait, but a tool for shaping public opinion through readily available material culture. Curator: The nuances of this era never fail to amaze. Reflecting on our discussion, it is so compelling how a formal portrait can tell us so much about religion, belief and the everyday practices of a world that's increasingly centered on consuming and circulating reproducible images. Editor: Precisely. This image reminds us of art's entanglement with the very infrastructure of belief and knowledge systems. By recognizing such complex purposes in portraits, we move towards a more rounded historical lens.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.