drawing, paper, ink

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

#

charcoal drawing

#

figuration

#

paper

#

ink

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

Dimensions: 205 mm (height) x 577 mm (width) (bladmaal)

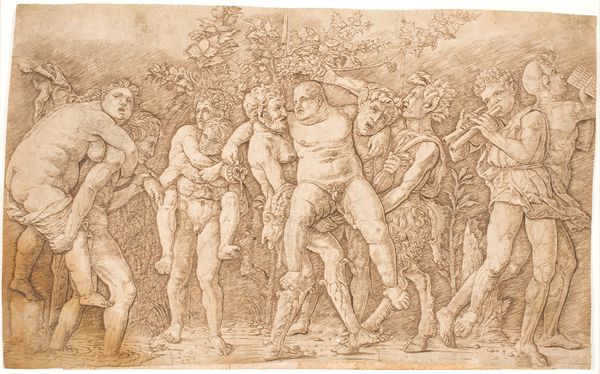

Curator: The right half of an arresting drawing rendered in ink on paper. It depicts, according to its title, The Rape of the Sabine Women, dating from sometime in the 17th century. The museum attributes it to an anonymous maker, a haunting fragment capturing the chaos of conquest. Editor: There’s a stark violence in the figures; the musculature exaggerated, locked in this timeless frieze, feels more about dominance than drama. The lack of color, the brown ink, seems to suck the warmth out of the scene, leaving only the aggression. Curator: Indeed. Consider how the draughtsman uses ink and charcoal to emphasize not only musculature, but the drapery in disarray around their limbs—symbolic, perhaps, of the tearing of societal fabric that war precipitates. There’s a visual rhythm, a constant pulse that recalls the tradition of triumphal arches from Roman antiquity, mythologizing these narratives for later eras. Editor: But mythologizing normalizes this violence. What purpose is served when art simply enshrines brutal historical acts? The "rape" in the title points to not only abduction, but the erasure of women's autonomy—reducing them to possessions in power struggles. Curator: But aren't depictions of these violent acts part of grappling with history's uncomfortable truths? Visual imagery functions, psychologically, as a site where society negotiates with, reinterprets, or condemns behaviors that are otherwise easily lost. Artists working in the baroque aesthetic are very aware of the potent effects of violent symbolism on audiences. Editor: I wonder if focusing on technicalities eclipses grappling with why this imagery continues to pervade art history? Who does it benefit? I wonder, if we refuse to engage, does silence inadvertently perpetuate a cycle? We have a responsibility to deconstruct this iconography in a critical light. Curator: The dialogue, the interpretation itself, is an essential component of this preservation and allows new pathways into interpreting the cultural meanings in classical and biblical history—and understanding its legacy. Thank you for lending your insights. Editor: My pleasure. Let's remember art isn't separate from the messy world; it's deeply enmeshed in it, always capable of affecting, reflecting, and transforming social dynamics.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.