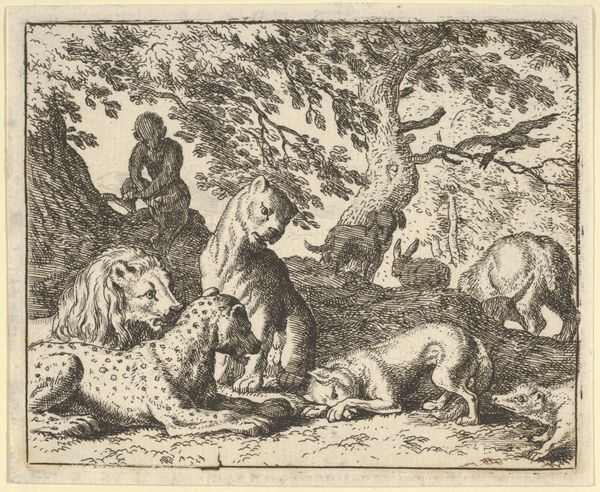

The Wolf in in the She-Monkey's Cave Where the Renard Convinced Him to Enter in Order to Make Fun of Him from Hendrick van Alcmar's Renard The Fox 1650 - 1675

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, ink, engraving

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

#

animal

# print

#

landscape

#

ink

#

engraving

Dimensions: Plate: 3 3/4 × 4 9/16 in. (9.5 × 11.6 cm) Sheet: 4 1/16 × 4 13/16 in. (10.3 × 12.2 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Here we have an engraving by Allart van Everdingen, likely dating from between 1650 and 1675. Its full, rather descriptive title is, "The Wolf in the She-Monkey's Cave Where the Renard Convinced Him to Enter in Order to Make Fun of Him from Hendrick van Alcmar's Renard The Fox." It’s currently held in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: What strikes me is how melancholic it feels despite the title suggesting mischievous trickery. The cave, rendered with these tight, cross-hatched lines, is dark and isolating. Curator: It's one scene from a cycle illustrating the medieval beast fable "Reynard the Fox", immensely popular in the Dutch Golden Age, that was ripe with social and political commentary through anthropomorphic characters. This work highlights the vulnerability of the wolf through this specific printmaking method, with its implications for seriality and availability. Editor: The choice of engraving allows for the creation of detailed, reproducible images, making the narrative accessible to a wide audience, reflecting a consumer culture interested in moral tales and satires. And you’re right, you can see the meticulous labor involved. What really intrigues me is how the light falls on the wolf. He appears almost caught in the act, a bit bewildered. Curator: Consider too how prints at the time functioned within a competitive visual economy. The story itself gained renewed significance with a rising middle class. Its concerns with morality, class, and ambition were readily accessible because they engaged viewers directly in these new forms of visual media and narrative tradition. Editor: Definitely. You know, despite the intended satire, there's an undeniable sympathy evoked for the wolf in this poor lighting and cramped setting. Perhaps we see a little of ourselves in his misjudgment. The contrast makes the cave feel less like a den of ridicule and more like a stage for our shared follies. Curator: And there’s also the broader implications about the labor required, not only in the artist’s making of the engraving, but also the consumption and the story’s message within the contemporary Dutch context. Editor: True. So much about how we interact with narratives remains unchanged even now. It just highlights how accessible this kind of satire made morality to the people through art at that time. I do feel that wolf should’ve seen the setting for the set-up that it was.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.