photography

#

portrait

#

17_20th-century

#

landscape

#

archive photography

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

historical fashion

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: height 190 mm, width 260 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

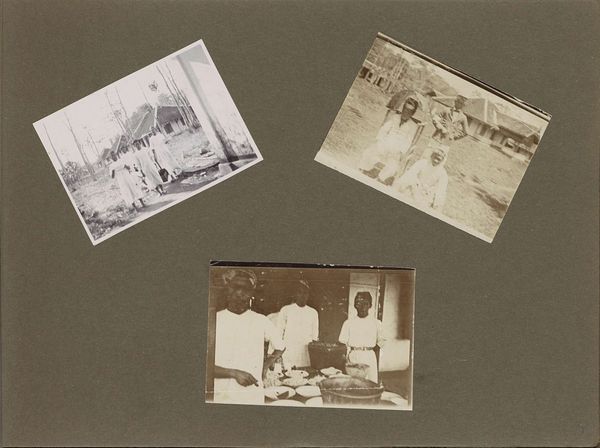

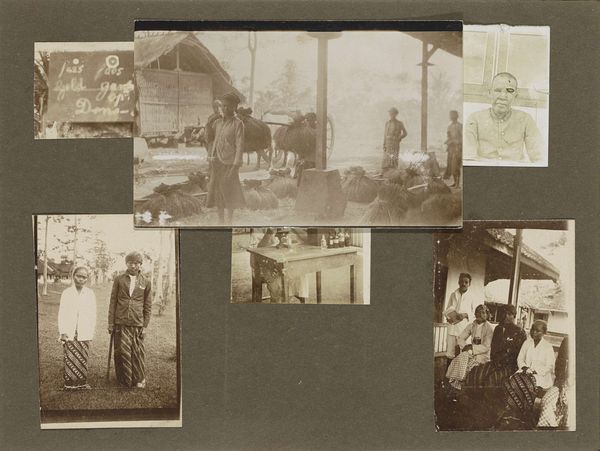

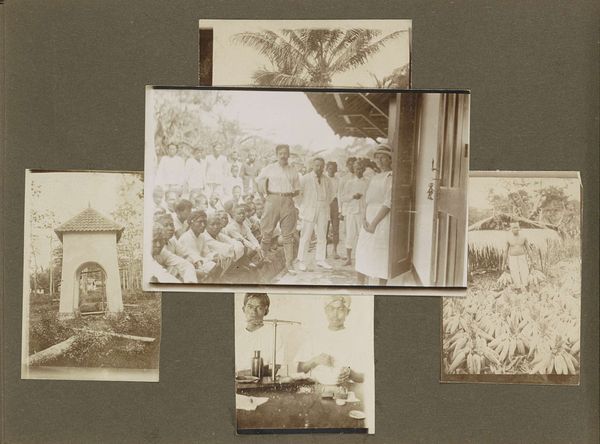

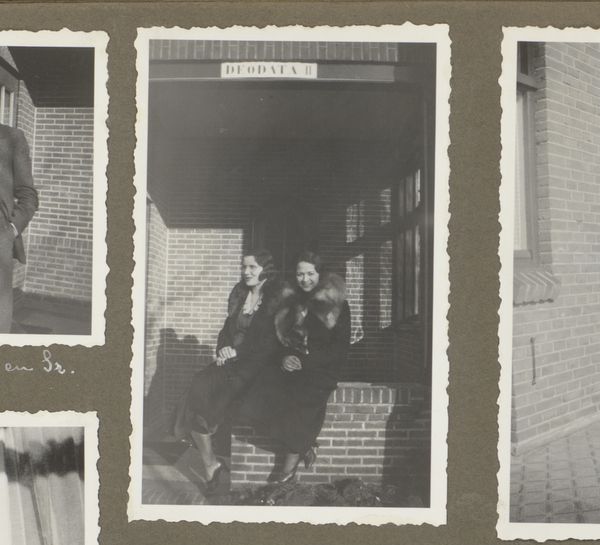

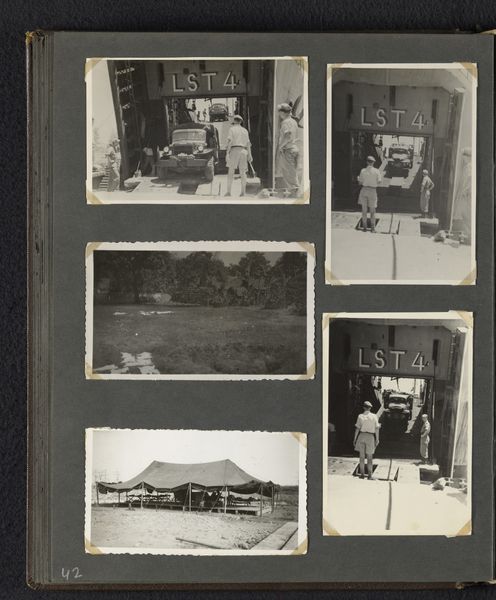

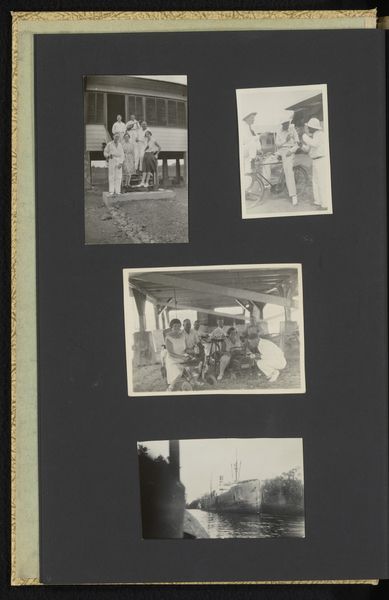

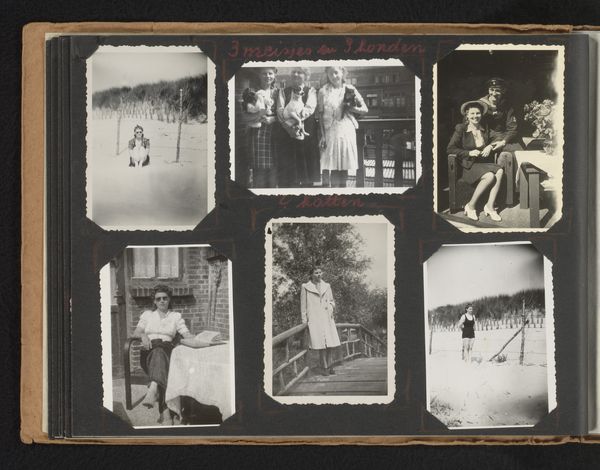

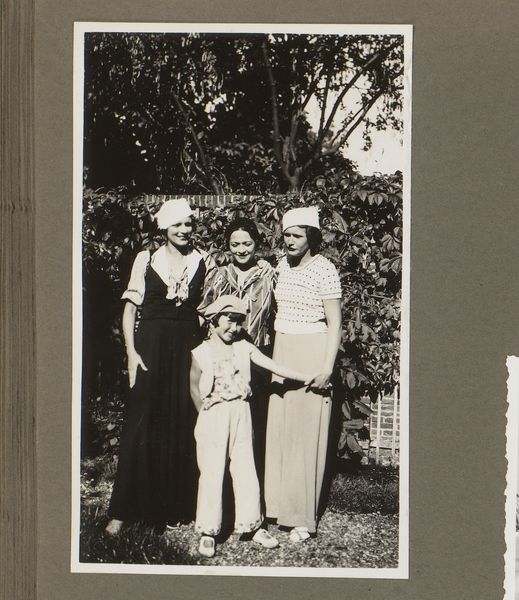

Editor: This is a photographic work titled "Leprozenkolonie Danaradja: familieportret en gebouwen," created around 1922. It seems to combine a family portrait with architectural images of the colony. There is a peculiar, melancholic mood. What catches your attention when you view this piece? Curator: The image immediately sparks questions of power dynamics and representation within colonial contexts. We see a European family, presumably in a position of authority, juxtaposed with images of the leper colony. Who is taking this photograph and what are they trying to say about their relationship to those they are ostensibly helping or governing? Editor: That's interesting. I hadn't considered the power dynamics so explicitly. I was more focused on the juxtaposition of personal and institutional spaces. Curator: Exactly! Consider the genre of "family portrait." It suggests intimacy, domesticity, perhaps even benevolence. But placing it alongside images of the colony disrupts this narrative. What does it mean to document a disease and the segregated populations in such a detached way? And, importantly, how might this image reinforce, or perhaps unintentionally critique, colonial structures? Editor: So you’re saying the photograph becomes a document of the colonial gaze itself? Curator: Precisely. And by looking closely at elements such as dress, posing, the architecture in each photograph, we can begin to unpack the complex intersectional layers of race, class, and health at play during this period. Consider Foucault's ideas of biopower. How does the photo normalize, or make banal, a deeply unequal dynamic? Editor: That makes me look at it completely differently now. I had considered it more as a simple historical record, but now I see how much it reveals about colonial ideology. Curator: Historical images like these require critical viewing habits, a willingness to dissect them as visual arguments, revealing both intended and unintended power structures and how they intersect to create particular historical moments. Editor: I appreciate you pointing out the historical and cultural context. It’s pushed me to think more deeply about the photographer’s role and perspective in crafting this image. Curator: And for me, reflecting on these early images reminds me of the urgent need for socially conscious contemporary art making. We must use these historical narratives to critique present power structures and strive for true equity and representation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.