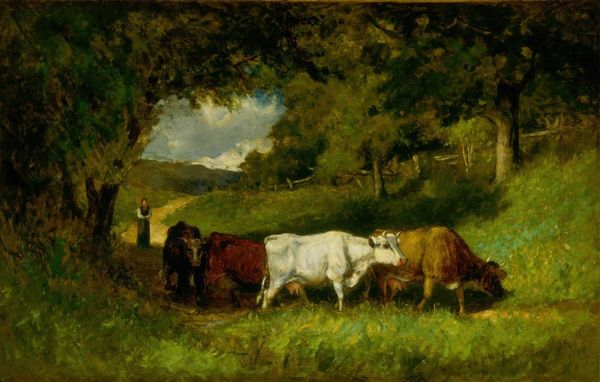

painting, oil-paint

#

portrait

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

landscape

#

oil painting

#

romanticism

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

realism

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

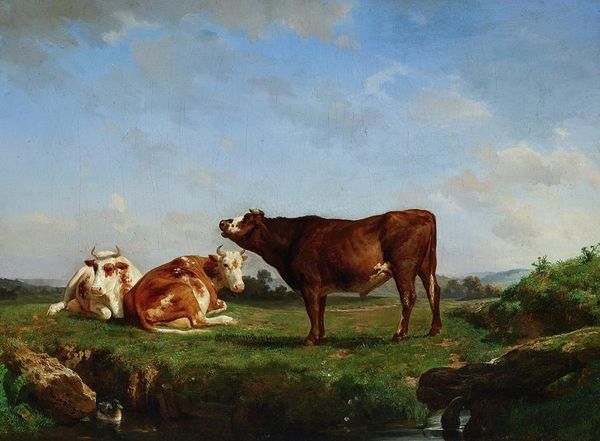

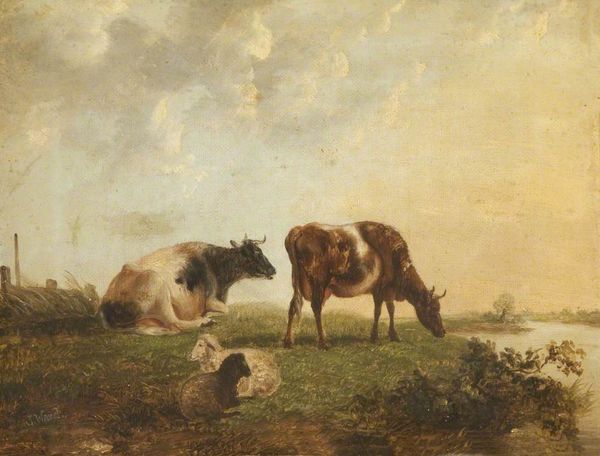

Curator: Immediately, I'm struck by how subdued it is. The sky is vast but heavy, the colors muted, the whole scene bathed in a sort of wistful tranquility. Editor: Indeed, Rosa Bonheur painted this pastoral scene, entitled "Shepherdess and Two Cows in a Meadow," around 1842 to 1845. The artwork makes skillful use of oil paint. It feels very deliberate, doesn't it? The weight of the materials reflecting the reality of agricultural labor. Curator: Absolutely. Bonheur elevates this mundane scene into something almost allegorical. The shepherdess, so self-contained with her spindle, embodies the quiet strength and industry of rural womanhood. It feels deliberately timeless, harking back to classical ideals of bucolic life. She has roots, a sense of deep belonging. Editor: Note the labor involved. Bonheur clearly understood the physicality of tending livestock, of managing the land, she gives dignity to their lives by demonstrating those material processes. The animals themselves aren't sentimentalized. They're rendered with a strong sense of realism, showing her commitment to directly recording how cattle looked. Curator: The cowherd in the distant background really reinforces that connection, and shows she knew her role. Speaking of realism, there's almost a folk-tale quality to the colors and to how all living things interact in this composition. It evokes not just an image, but also the broader narratives, traditions, and beliefs associated with rural life. What looks idyllic isn’t just beauty; it holds a record of cultural value and how work becomes meaning. Editor: Precisely. The labor is the point. Bonheur's technique demonstrates how closely linked production, skill, and value really are. The layering of paint, the carefully observed details… it’s all labor rendered materially, just like the shepherdess working in the field. Curator: This feels like Bonheur asks the viewer to connect deeply to how people construct meaning within nature itself, both personally and through community labor and belief systems. This resonates deeply still, given our ongoing connections to—and disconnects from— the landscapes that still nourish us. Editor: It's quite compelling when you consider art history this way: what are the means of the artwork's production? It makes you think about our present forms of creative work, as well. Curator: It certainly provides much food for thought. Editor: Indeed it does.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.