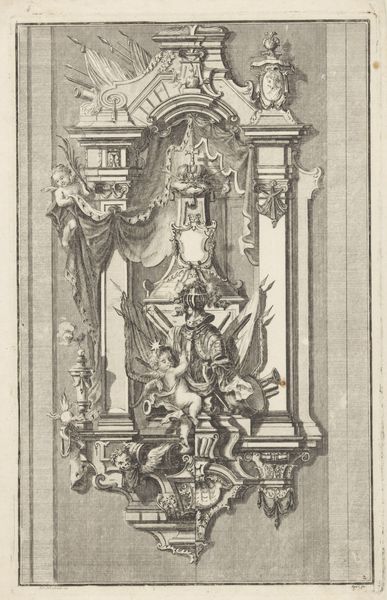

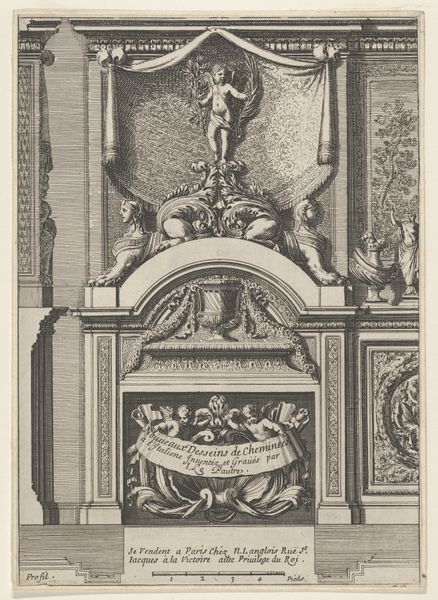

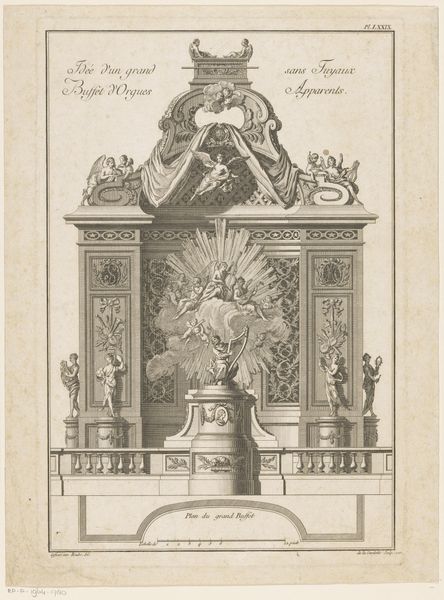

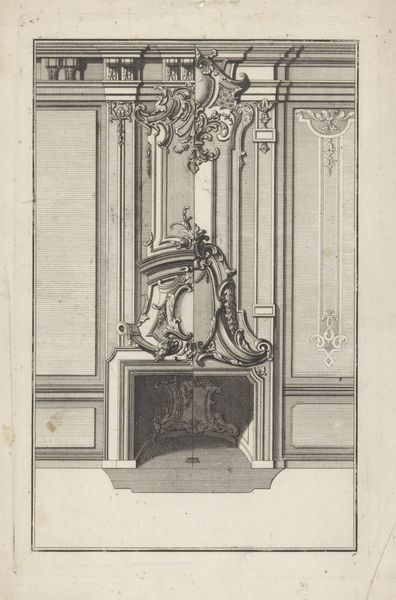

print, engraving, architecture

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

architecture

Dimensions: height 288 mm, width 176 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

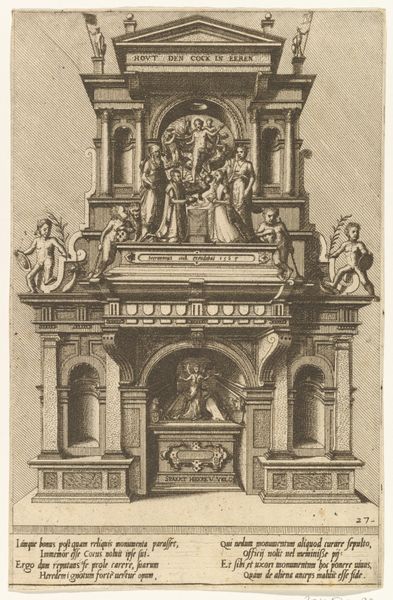

Curator: So, we're looking at "Waterpomp met slangen en varkenskoppen," or "Water Pump with Snakes and Pig Heads," an engraving created after 1724. It's currently held in the Rijksmuseum collection. What strikes you right away? Editor: A playful sense of fantasy—architectural rendering meets beastly adornment. I'm drawn to how the serpentine forms interact with the otherwise stately structure. There is this almost macabre celebration of natural forces made to serve humans in some alchemical game. Curator: Exactly! Lichtensteger's expertise in printmaking really comes through. Engravings such as this played a key role in disseminating designs and architectural ideas during the Baroque era. Think of it as an early form of design cataloguing. Editor: You see a calculated catalog, but my eyes see a grand dance! Consider the tension between the formal geometry of the architecture, like the columns and arches, versus the very lively and arguably grotesque figures he’s placed as focal points. I am particularly arrested by the pig heads spurting out the water; pigs in such grand depictions suggest so much abundance and the strange vitality of everyday life. Curator: Absolutely, there's a dialogue here about status and self-perception. Water, essential for life and, in fountains, traditionally signifying prosperity and divine favor, gushes forth from creatures that, in a different context, could symbolize earthly desires or base instincts. Editor: These layers, as you indicate, really fascinate me. Even the lone figure operating the pump—his presence emphasizes control over nature, fitting perfectly into the Baroque ethos of dominance and spectacle. What would this pump be delivering? Death or rebirth? Daily nourishment, or access to grandiosity? The fact that the rendering exists as a piece of architecture—even when it would be near impossible to practically create the structure—speaks to the iconographic project that the original artist intended. Curator: It's an interesting dance between function and display—that’s for certain! These water pumps transcended mere utility; they were about displaying wealth, controlling the natural environment, and, more broadly, articulating one's position within society. I think, by combining these symbols, Lichtensteger's work continues to speak across generations. Editor: And it seems it dares us to rethink where we place our faith, perhaps our values, as our water changes hands. What we venerate today becomes fertilizer tomorrow.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.