print, engraving

#

narrative-art

# print

#

figuration

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 232 mm, width 260 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

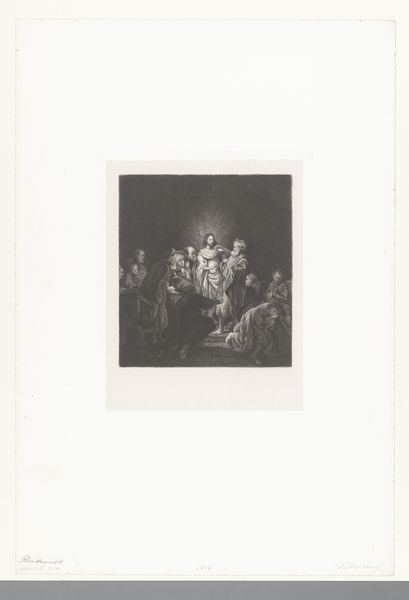

Editor: This is "Christus en de overspelige vrouw" or "Christ and the Adulterous Woman" by William Unger, made sometime between 1847 and 1889. It's currently housed here at the Rijksmuseum. Looking at it, the scene feels heavy with judgment, the dark engraving intensifying the woman’s shame. What kind of societal commentary do you think Unger might be making? Curator: Well, let's consider Unger’s position in 19th-century Europe. The image comes in the wake of widespread religious revival and growing anxieties around moral order. He is working within, and in dialogue with, very specific socio-political structures. To me, the image is a visual manifestation of this tension. Who does this space truly belong to, and how are the lines of gender and class performed in its presence? Editor: So it's less about personal judgment and more about examining power dynamics at the time? I’m curious how Unger’s choice of printmaking as a medium informs this interpretation. Curator: Exactly! Printmaking enabled broader distribution and democratization of imagery, positioning "Christ and the Adulterous Woman" in numerous public spaces, potentially igniting varied interpretations across diverse social strata. Can the mass reproduction affect its inherent power? What new audiences engage with that power as it circulates outside the institution? Editor: I see. So the choice of medium challenges the exclusive understanding of religious and moral stories, which traditionally stayed with those in power, like the church or wealthy patrons. I had initially focused on the scene’s mood, but now I see a wider commentary about social roles. Curator: Precisely. It is a question about visual language being democratized, so it also opens interesting conversations on both control of the narrative and who should control its narrative. It shifts it to be something public instead of something within elite spaces. Editor: Thanks, that's a fantastic perspective. It’s really interesting to consider the engraving not just as art, but as a historical document about the dissemination of social values. Curator: It certainly helps reshape the narrative. Seeing art as embedded in historical institutions really helps us unpack its potential, and limitations.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.