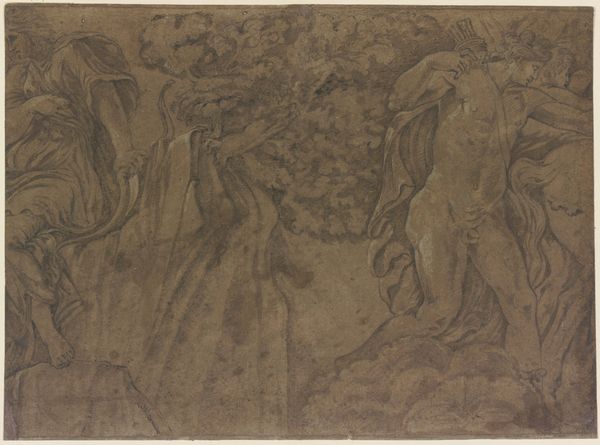

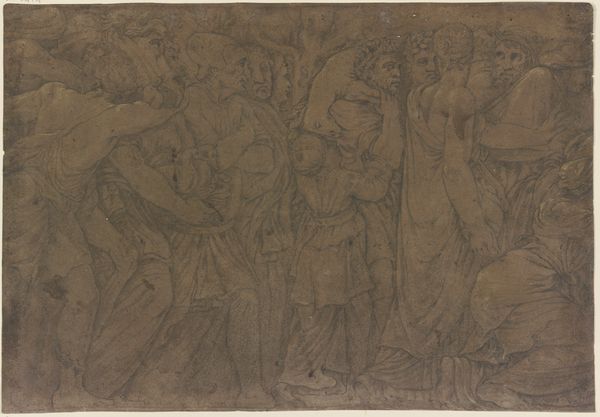

Der verlorene Niobidenfries an der Fassade des Palazzo Milesi in Rom 1656

0:00

0:00

drawing, paper, ink, indian-ink

#

drawing

#

high-renaissance

#

baroque

#

figuration

#

paper

#

ink

#

ink drawing experimentation

#

underpainting

#

indian-ink

#

13_16th-century

#

14_17th-century

#

history-painting

Copyright: Public Domain

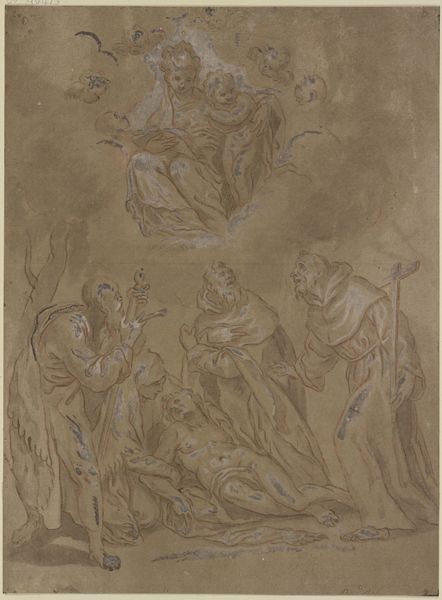

Curator: What strikes me immediately is the pervasive sense of muted solemnity. The sepia tones lend it an air of antiquity, and the composition seems carefully constructed, perhaps referencing classical friezes. Editor: Indeed. This is a drawing by Polidoro da Caravaggio, dating to 1656. It’s titled "Der verlorene Niobidenfries an der Fassade des Palazzo Milesi in Rom" and is currently held at the Städel Museum. Curator: Fascinating. Looking at the layering of forms, I note a certain dynamic tension between the individual figures and the unified whole. Polidoro clearly emphasizes classical form and proportion, adhering to a tradition where the interplay of lines creates spatial depth. Editor: Precisely. And what's intriguing from a material perspective is Polidoro's use of ink on paper, specifically, the choice to employ primarily Indian ink. Consider how that informs the historical and practical constraints, for one it influences its preservational integrity; Polidoro could only get so much saturation of darks on his tonality. This would certainly speak to the fresco process on site where this drawing may be only one aspect of design on this project. Curator: That's insightful. The gradations achieved are masterful, suggesting perhaps a symbolic interplay of light and shadow, echoing the high-renaissance and early baroque periods of figuration within which it falls. Editor: Furthermore, the condition and materiality point to the circumstances of its making; it presents the relationship between labor and capital within the baroque era’s architecture and production processes. These lost murals only survive as this study, what can this tell us about what has value and what can be discarded in our cultural memories? Curator: A vital point. It is precisely this duality, isn't it? It captures both grand narratives and fragile, individual narratives of materiality and execution of labor simultaneously. Editor: Perhaps in the end, through understanding his technique, we see this not merely as documentation but a tangible reminder of the cultural machinery within society at large. Curator: Absolutely. Studying the aesthetic form unveils a glimpse into the cultural memory itself. Editor: And conversely, by focusing on material applications and social implications we might broaden the horizon through a simple, monochromatic, and historical frieze.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.