drawing, pencil, graphite

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

11_renaissance

#

pencil

#

graphite

#

northern-renaissance

#

charcoal

#

realism

Copyright: Public domain

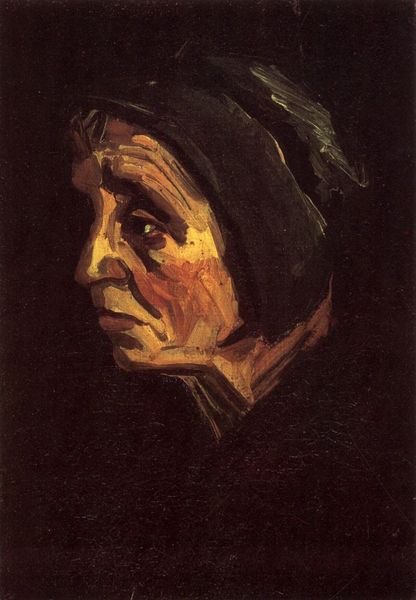

Editor: Here we have Albrecht Dürer’s "St. Anna (Portrait of Agnes Dürer)," from 1519. It's a drawing, rendered in graphite and pencil. I find it quite striking, almost haunting. What can you tell me about it? Curator: What grabs me immediately is the evidence of labor and process. We're looking at raw materials – graphite and pencil on paper – transformed through skilled labor. Consider the socio-economic context. Paper, pencils, these weren't universally accessible. Their availability signifies a level of privilege. Does it shift your understanding of the "haunting" quality you mentioned? Editor: Definitely. Knowing more about the materials changes my perception. It highlights a divide between who could be portrayed and who could afford to portray them. Did the choice of graphite impact the image beyond the socioeconomic factors? Curator: Absolutely. Graphite offers a specific texture and sheen, different from, say, charcoal. Dürer's choice contributes to the overall aesthetic, reflecting the material possibilities of his time, as well as his labor decisions of where to put his dark marks. Think about how the material itself shapes the message, moving beyond just representation. Does that makes sense? Editor: Yes, that’s very insightful! I hadn't considered the agency of the material itself. It's like the graphite had a say in how the portrait turned out. Curator: Precisely! It forces us to acknowledge artmaking as an act embedded in a web of materials, processes, and societal conditions, dismantling any romantic notions of pure genius divorced from the physical world. How different from art that valorizes the artist above all else! Editor: I see what you mean. Examining the materials and context really exposes the layers within the artwork. Curator: Exactly. By understanding the artwork's materiality and its production, it becomes a point of departure towards better understanding labor. We unveil so much about the period, the artist, and, ultimately, ourselves.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.