sculpture, wood

#

sculpture

#

wood

#

indigenous-americas

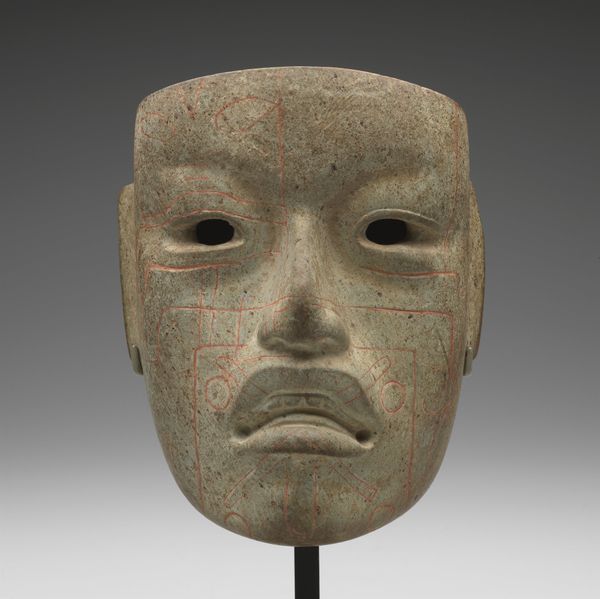

Dimensions: 11 3/16 x 11 1/2 x 3 1/8 in. (28.42 x 29.21 x 7.94 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: This striking mask, dated to between 1850 and 1900, crafted by an Inupiaq artist, employs wood and pigment in its construction. It's both captivating and unsettling with its simplistic yet direct gaze and peculiar set of teeth. What stands out to you when you examine it? Curator: What interests me are the tangible components and the act of production. Notice the selection and preparation of the wood—was it locally sourced? How does its grain influence the form? Pigment analysis could reveal the materials at hand and trade routes influencing their availability. This connects artistic expression to labor and broader consumption habits of the Inupiaq people. Editor: That’s an interesting point. It makes you think about where all the different pieces come from, literally. Does this mask relate to other indigenous art from the United States, in terms of its materiality? Curator: Absolutely. By examining other masks and objects created by the Inupiaq people, and those of other Indigenous groups of the United States, we may discover similarities and differences in material use influenced by environmental factors, cultural traditions, and the introduction of goods through trading networks with Europeans. Understanding the physical composition tells us more about how these people are affected. What function might the teeth have played within rituals or performances associated with the mask? Were these commercially produced goods, bartered for, or organically sourced locally? Editor: It definitely makes you wonder about its specific function. Learning more about the social conditions and trading possibilities surrounding it gives this mask so much greater context. Curator: Precisely. Focusing on the process allows for an understanding that expands beyond conventional aesthetics, challenging boundaries by integrating social and economic dimensions into artistic dialogue. Editor: Thanks! Thinking about the material components of artwork has completely transformed the way I see it. Curator: A materialist approach is an ongoing process! Keep questioning those means of production!

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

Among the Yup’ik of the Arctic region, masks were made for ceremonial purposes, and their subjects were humans, animals, and spirits. Each mask is unique because its details are given to the carver in a dream. The masks are used for healing ceremonies or community-based dance celebrations such as the Bladder Ceremony. This mask could have elements from both a human and a bear, which may show the transformation from one being into the other. The Yup’ik, like many Native American cultures, consider bears to be part human. The ears are proportionally large because the Yup’ik believe that bears have an acute sense of hearing. In fact, they would be very careful what they said about bears because their conversation could be heard for miles and could anger the bears. Most Yup’ik masks had extensions around the perimeter of the object; these could be a large wooden circle, feathers, or both. The majority of masks in museum collections have lost these elements because of their fragility.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.