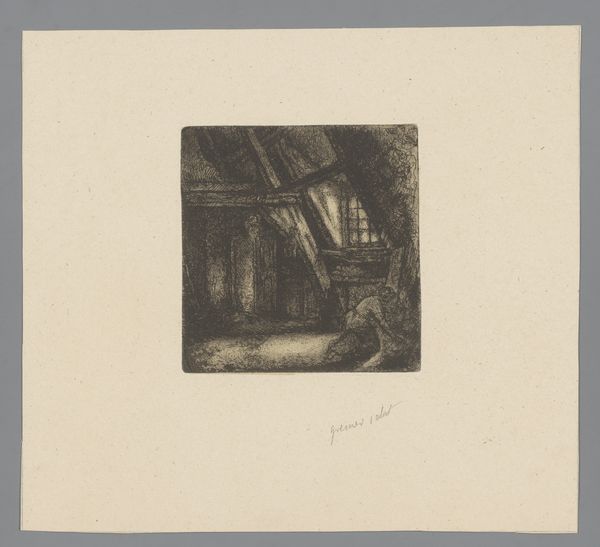

drawing, print, etching, ink

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

# print

#

etching

#

figuration

#

ink

#

pencil drawing

#

history-painting

Dimensions: height 162 mm, width 124 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Immediately, the cross-hatching in this etching gives the scene a hazy, dreamlike quality, like looking back through time. Editor: Indeed. What we have here is a print entitled "Monk and a Knight on his Deathbed," created by Léopold Flameng between 1841 and 1910. Its reliance on line work reminds me of printmaking's reproductive capabilities during this time. Think about the democratization of imagery, reaching wider audiences through printed matter. Curator: Absolutely, the accessibility changes the status of history painting and its perceived audience. The etching process itself allows for a striking level of detail – observe the intricate armour discarded on the floor beside the dying knight’s bed. The method involves carefully layering lines and textures which contributes significantly to the overall visual weight and dramatic intensity. Editor: Considering the period, one has to ask what this print says about heroism. The church is present at his death, a kind of spiritual reassurance—however, note also the implements of warfare are laid out on display almost like relics, sanctifying and monumentalizing martial exploits. This begs the question of whose story we’re really meant to empathize with, and, therefore, memorialize? Curator: Good question. I notice the presence of that intricately rendered gothic style tabernacle with tiny pinnacles sitting like a memorial or placeholder on that bedside table! To me, the care devoted to capturing the materiality of that object indicates an interesting reverence on Flameng's part. It definitely underscores the presence of faith and the visual language surrounding late 19th-century spirituality. Editor: Flameng made the conscious choice to situate this private moment within a broader societal and historical context. It almost challenges how we, as a public, are encouraged to view historical figures – less as mortal individuals, and more as symbolic figures. The setting within what seems like a stage gives rise to thinking about presentation, performativity, and the way images work in society. Curator: From my point of view, paying attention to the physical process behind it allows for another interpretation that focuses on labor: on Flameng’s own skill and the material properties of etching ink, the paper support, the distribution and value in society… All of which speak to larger systems beyond what the images themselves illustrate or suggest thematically. Editor: I appreciate that material insight, that there's so much value in considering how making and labor factor into interpretation. This has certainly shifted my perception of the work! Curator: Likewise, this contextual information opens a new portal through time when considering art in public collections and museums.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.