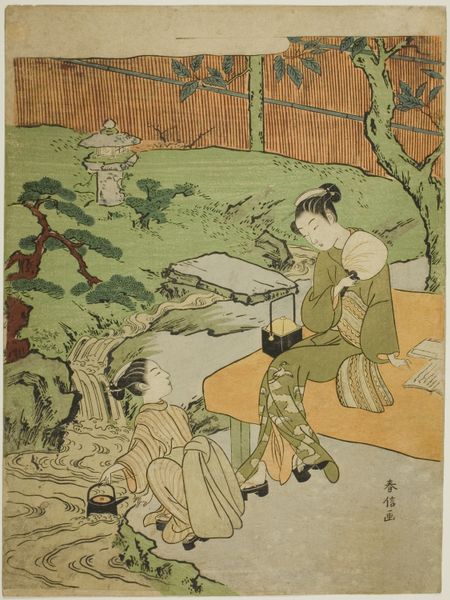

The Third Month (Yayoi), from the series "Popular Versions of Immortal Poets in Four Seasons (Fuzoku shiki kasen)" c. 1768

0:00

0:00

print, woodblock-print

# print

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

ukiyo-e

#

figuration

#

woodblock-print

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: 28.8 × 21.6 cm (11 3/8 × 8 1/2 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Welcome. Today, we’re observing Suzuki Harunobu’s woodblock print from around 1768, titled "The Third Month (Yayoi), from the series 'Popular Versions of Immortal Poets in Four Seasons'." It's a Ukiyo-e piece housed right here at The Art Institute of Chicago. Editor: Immediately striking, isn’t it? The subdued palette and flattened perspective create a tranquil scene. There’s a stillness in the air, despite the flowing water. I find myself drawn to the textures. Curator: Yes, the tranquility certainly pervades. Considering its place in the broader Ukiyo-e movement is critical here, especially thinking about depictions of women. Notice how Harunobu veers away from overt sensuality common in earlier prints. Editor: I appreciate the subtle detailing of their garments, which suggests considerable skill and labor. What materials were used? It’s captivating how the layers create depth. Curator: Exactly. Woodblock prints involve precise carving, inking, and printing processes. It's incredible to think of the material constraints – the artist worked laboriously with wood, pigment and paper. Now think, the kimonos themselves become part of this broader examination of the social status and evolving roles of women in 18th-century Edo society, defying straightforward depictions of the male gaze. Editor: I’m particularly drawn to the water element, its delicate ripples suggest movement while staying perfectly still. What does this dichotomy tell you? Curator: I agree that the element is well placed in the work. Beyond formal components, such streams in this series are interpreted as signifiers for a fleeting, feminine sense of change, representing fluidity that’s closely intertwined with their personal journeys, questioning fixed narratives regarding identity and beauty within a patriarchal framework. Editor: Indeed, considering its material roots and cultural context adds immense layers to our perception, as those depicted probably weren't meant to mirror the female condition but merely the social and creative structures of the period. Curator: It’s about viewing artworks not as standalone aesthetic pieces but rather a form of tangible history. They spark insightful discussions. Editor: Indeed! Analyzing craftsmanship with its history and social context shows how it captures social change to inspire and resonate still.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.