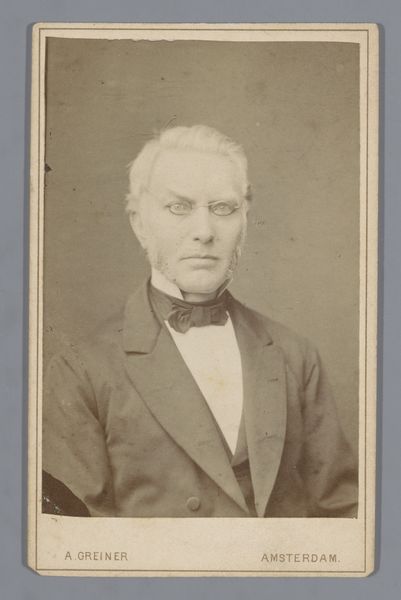

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

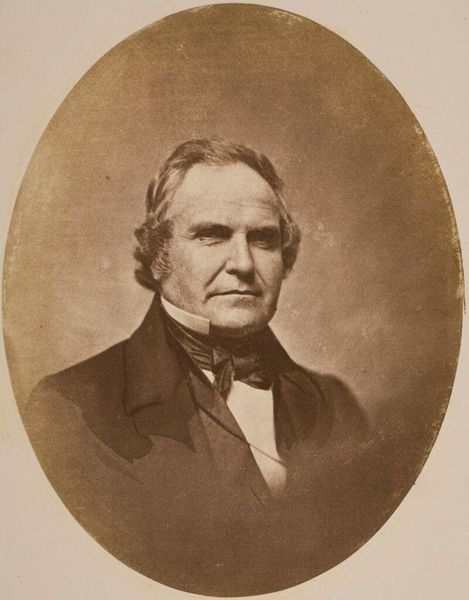

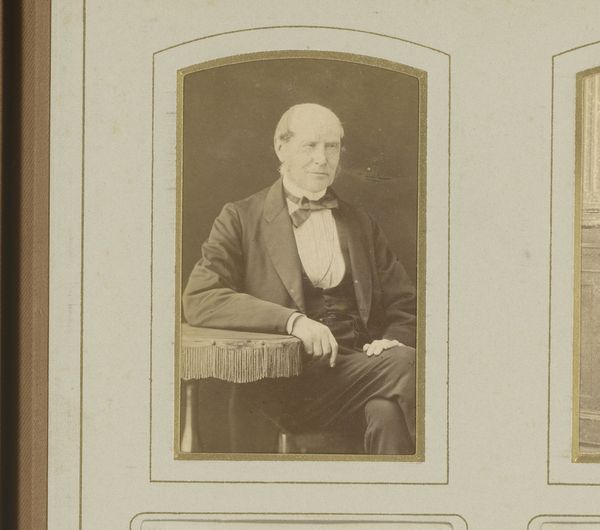

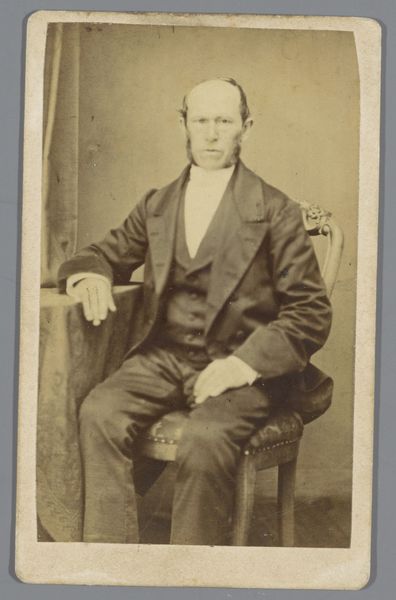

portrait

#

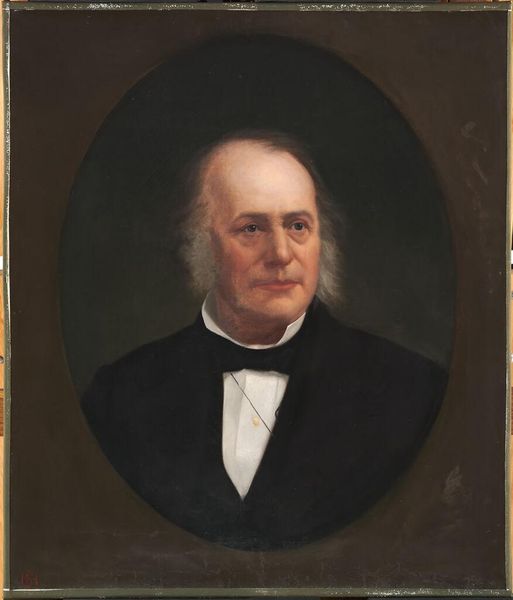

portrait

#

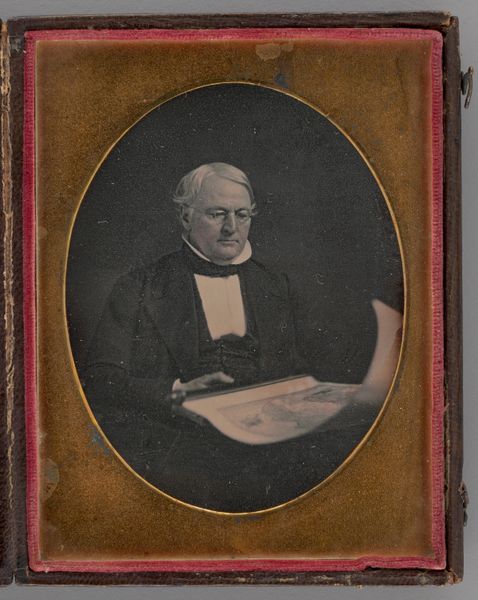

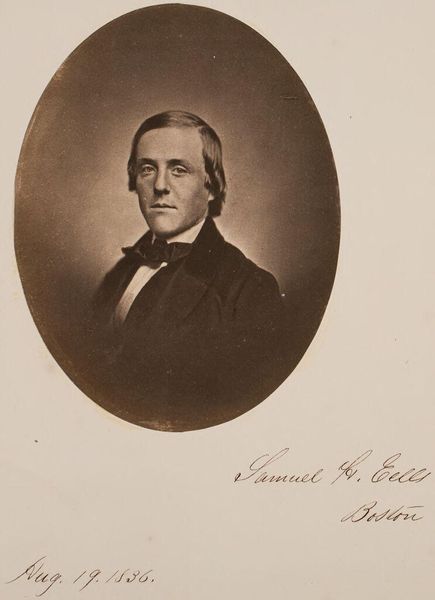

photography

#

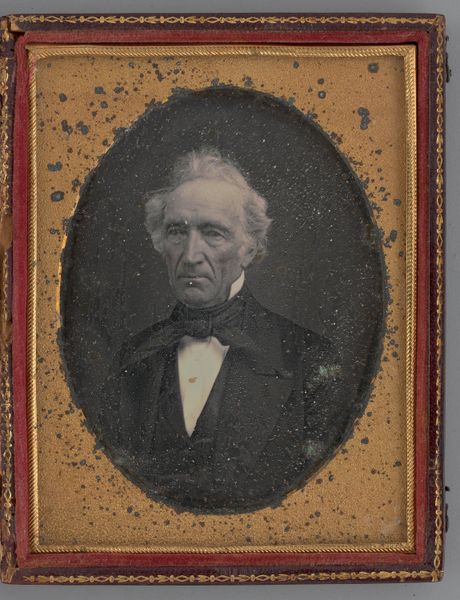

gelatin-silver-print

Dimensions: image (visible): 8.8 × 7 cm (3 7/16 × 2 3/4 in.) mat: 10.7 × 8.2 cm (4 3/16 × 3 1/4 in.) case (closed): 11.8 × 9.4 × 2 cm (4 5/8 × 3 11/16 × 13/16 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: This is a gelatin silver print portrait of Captain Gideon Lane, circa 1855, attributed to Hamilton Campbell. What's your initial impression? Editor: The overwhelming darkness is what strikes me first. It has a sombre and imposing presence; you sense power, but perhaps tinged with weariness. Curator: Absolutely. Considering it's a photographic portrait from the mid-19th century, that somber quality might be linked to photographic techniques and their relationship to social hierarchies. Campbell was likely working within conventions about portraying social stature through serious facial expressions, costume and light to assert authority, class and gender for the Captain. The flowers might hint at the power relations as a man receiving this honor. Editor: The question of agency, doesn't it? Was Lane seeking that portrayal or was it determined by photographic norms and cultural ideals surrounding masculinity? What does this say about representation and construction of the ideal male image in that period? Curator: Precisely. The visual conventions served as social technologies shaping selfhood and influencing viewers' perceptions. Also, look at the framing - the elaborate gold and the ornate oval format contributes to an aesthetic meant for the elite. Campbell's choice is never neutral. It situates Captain Lane firmly in the powerful segment of 19th century society. Editor: It raises questions about access and the role photography played in consolidating and perpetuating these social divisions. This image then goes beyond representing just one man; it's an archive of Victorian values and class awareness. Curator: And by deconstructing these embedded ideologies, we enable audiences to reflect upon the evolution of power and representation, past and present. Editor: It allows us to investigate photography as a means to re-examine the politics embedded in the production of such portraits. Thank you! Curator: Thank you. It enriches our engagement when considering who controls these powerful images and whose stories are being told.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.