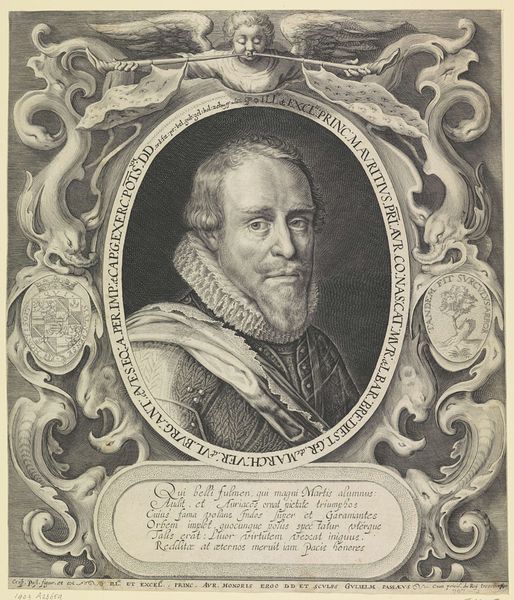

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

pen drawing

#

shading to add clarity

# print

#

figuration

#

line

#

pen work

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 210 mm, width 159 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have a print from 1622 titled "Portret van Hendrik Arentsen Vapoer," made by Simon van de Passe. Editor: My immediate reaction is how intensely detailed it is. Look at the crisp lines defining that elaborate ruff and the shading giving form to his face. It almost feels sculptural despite being a print. Curator: Exactly. As a print, it’s part of a much larger visual culture. Portrait engravings like this were instrumental in disseminating images of important figures. It helped establish a visual rhetoric of power and status. Notice the decorative framework, replete with allegorical figures, further cementing Vapoer's position. Editor: I'm particularly struck by the texture created by the engraving process. It makes me think about the physical act of production – the labor involved in meticulously carving those lines into the plate, the choices made about where to emphasize shadow and form. It transforms a flat surface into something seemingly three-dimensional. Curator: Precisely. Engravings such as this portrait operated within specific social and economic frameworks. These prints catered to a growing merchant class eager to participate in the culture of nobility. Editor: I agree. Think about the market for prints, how they were distributed and consumed. Prints democratized access to imagery, moving away from unique painted portraits only affordable to the elite. How do we consider this work within shifting dynamics between art and craft? The skill of the engraver is undeniable, but so too, is the social function it served. Curator: It's about understanding the politics of representation in early modern Europe, especially as religious and political conflicts intensified across the continent. Who controlled the image, and to what ends? How are historical narratives built around portraits such as this? Editor: Seeing the work through the lens of materiality reminds me of the tactile relationship that the consumers must’ve had. Not necessarily just for decoration. As accessible printed materials, it seems it became useful for conveying historical data, social beliefs, and even humor! Curator: A vital medium, reflecting and shaping the perceptions of its time. Editor: Indeed, thinking through its materiality brings me closer to grasping its social role, the print’s presence in that time period beyond just aesthetics and artistry.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.