Personificatie van Frankrijk (Marianne) voor een legerkamp 1793 - 1795

0:00

0:00

francoismarieisidorequeverdo

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving

#

neoclacissism

#

allegory

#

ink paper printed

# print

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

line

#

cityscape

#

history-painting

#

engraving

#

realism

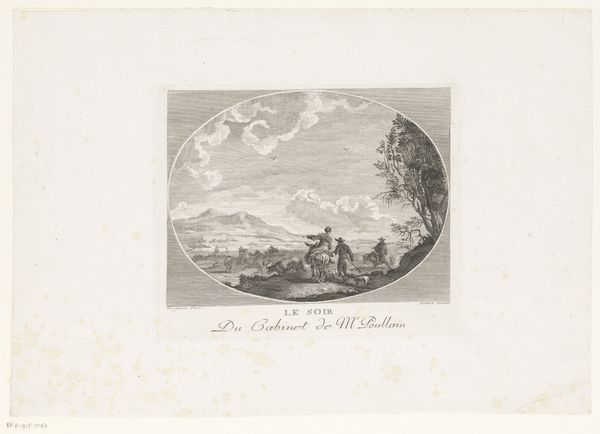

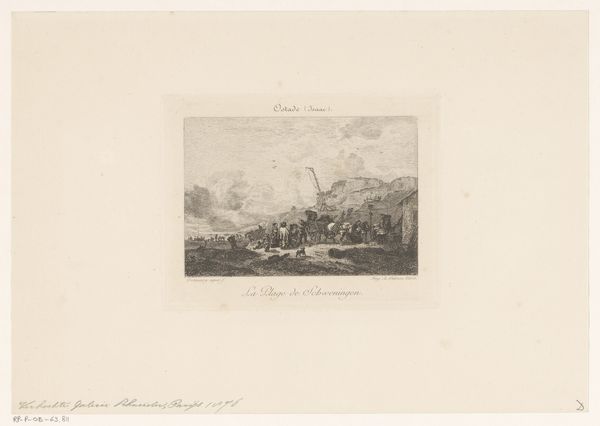

Dimensions: height 102 mm, width 133 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have “Personification of France (Marianne) before a Military Camp,” an engraving by François Marie Isidore Queverdo from around 1793-1795. It's quite striking, this symbolic figure dominating the scene against a backdrop of both domesticity and military preparation. How do you interpret this work, especially within the context of the French Revolution? Curator: It's vital to recognize the moment this piece inhabits: revolutionary France, caught between utopian ideals and the brutal realities of war. Marianne, as the personification of France, embodies the revolutionary spirit, but it's crucial to analyze *whose* revolution this represents. How does this idealized female figure negotiate the violence inherent in the revolutionary project? What does her passive pose say, seated amongst the tools of war, about female agency during this period? Editor: That's interesting. I hadn’t really considered her pose as potentially passive. I was viewing it more as dignified, a stable figure amidst chaos. Curator: Precisely. But the very act of representation is never neutral. Consider the inscription "République Française, Une et Indivisible"– an attempt to unify a nation deeply divided by class, gender, and political ideology. Is Marianne here a symbol of unity or a carefully constructed ideal masking deeper social fractures? Does this representation offer empowerment for all, or does it reinforce a patriarchal framework? Editor: I see your point. By understanding the different power dynamics at play in Revolutionary France, the image does seem to oversimplify and potentially exclude the struggles of women and other marginalized groups. Curator: Absolutely. And remember, this was commissioned by the “Comité de Salut Public,” a powerful arm of the state. So, while it visually promotes revolutionary values, it simultaneously functions as propaganda, worthy of deconstruction today. Editor: Thanks for highlighting those crucial questions! I’ll definitely look at art with a more critical eye toward the historical and social narratives they reflect. Curator: Likewise, this exchange is a valuable reminder that visual culture demands we continually re-evaluate what stories are told, and perhaps more importantly, *whose* stories remain unheard.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.