drawing, print, engraving

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

figuration

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: Sheet (Trimmed): 6 in. × 4 15/16 in. (15.3 × 12.5 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

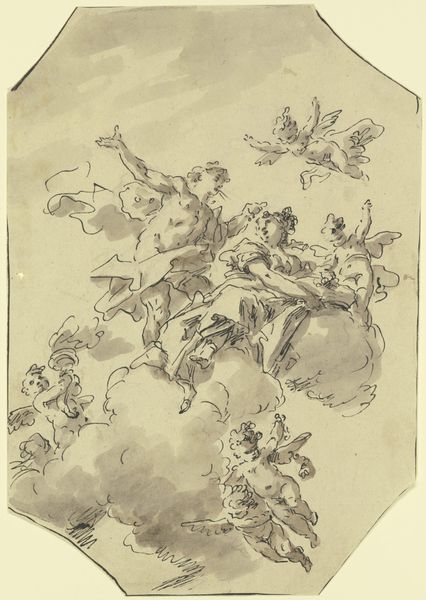

Curator: Here we have Carlo Innocenzo Carloni's "Putti Holding Flowers," an engraving dating back to between 1725 and 1775. Editor: My immediate impression is one of lightness and delicacy. The cherubic figures, almost floating, seem to dance on the surface. The monochrome tones create an ethereal, dreamlike quality. Curator: Indeed, Carloni, likely in collaboration with Johann Daniel Herz, skillfully employs line work to convey both form and texture. Notice how the varying density of the lines gives depth to the putti and the floral arrangement they carry. What strikes me is the artisanal labor involved in engraving; the painstaking process. Engravings were often used to disseminate images, democratizing access. This challenges the common narrative around aristocratic art. Editor: It makes me think about how depictions of childhood and innocence are, culturally, potent ideological symbols. These aren't simply cute babies; they embody ideas of purity, potential, and even the divine. We could examine the symbolism within the blooms; they're held aloft as if offered or presented to us, asking for our engagement in this innocent form of symbolic understanding. It brings into question a period defined by monarchy and class, juxtaposing pure and the corrupt. Curator: Exactly. These prints weren’t necessarily valued as high art but served more as functional tools. Studying such materials in their original context reveals a web of influence, skill, and consumption—and this shifts focus from romantic ideas about the artist’s creative vision, as separate from societal factors and market pressures. Editor: Looking closer, the implied action captures the shifting social attitudes towards childhood in 18th-century Europe. These were products intended for circulation, consumed within networks both defined by leisure and those in developing industrial centres. What do those shifts towards domesticity tell us about women of this time and their place in social frameworks of consumption? Curator: Absolutely. This was not just about art hanging on a wall. We gain a much fuller picture. Thanks to these layered networks of creation, distribution, and utilization, we've had a great chance to learn here about how images could traverse social boundaries and impact ideas. Editor: I couldn’t agree more, that has deepened my understanding so much, not only of the era, but our changing understanding of access.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.