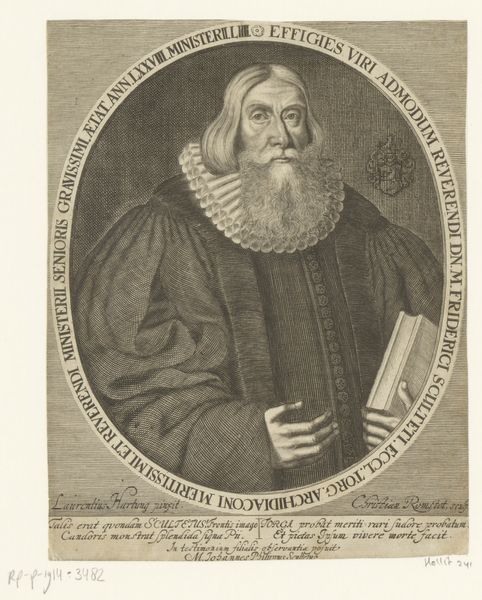

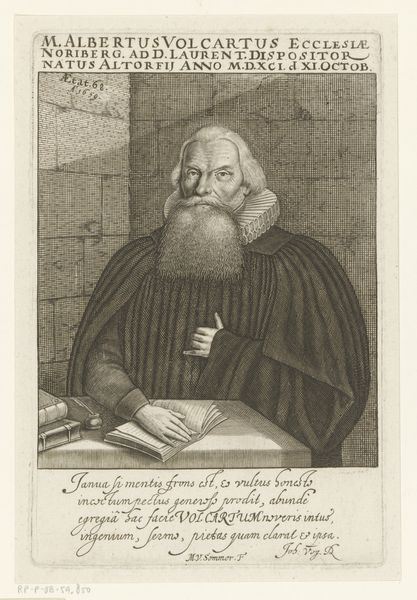

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 182 mm, width 138 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: We're looking at a portrait of Matthäus Hofmann, made sometime between 1665 and 1721. It's an engraving, and what strikes me is the formality – the inscription surrounding him, his solemn expression. How do you interpret this work, given its historical context? Curator: Well, considering this is a print, it speaks to the rising importance of image distribution and its role in shaping public perception. Portraits like these were often commissioned, playing a part in constructing the subject's public image and solidifying their position within the community. He was clearly somebody of some importance in his community to be depicted in such a way. The inscription tells us as much, can you read some of it? Editor: It seems to say "Matthaeus Hoffmannis Macheropoli," I guess that last word could be a place... and then "pastor." So he's a pastor from Macheropolis? Curator: Precisely! The very existence of this print signals that Hoffman’s identity, position, and memory mattered to a particular audience – perhaps his congregation, family, or even a wider intellectual circle. How do you think a print like this functions differently than a painted portrait? Editor: Well, I suppose the big difference is how widely a print can circulate. If it’s an engraving, like this one, multiple copies can be made and distributed, allowing Hofmann's image and his associated virtues to spread more easily. I never really thought about prints being used to shape opinions like that! Curator: Exactly. It is important to remember that the act of creating and distributing portraits—even printed ones—were a very politically and culturally loaded process back in the baroque era, especially in formerly highly charged environments following religious conflict. Editor: So much more to it than just a picture of a man. Thank you! Curator: Of course! Considering such elements help to show how deeply entrenched images are within complex networks of power, religion and public identity.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.