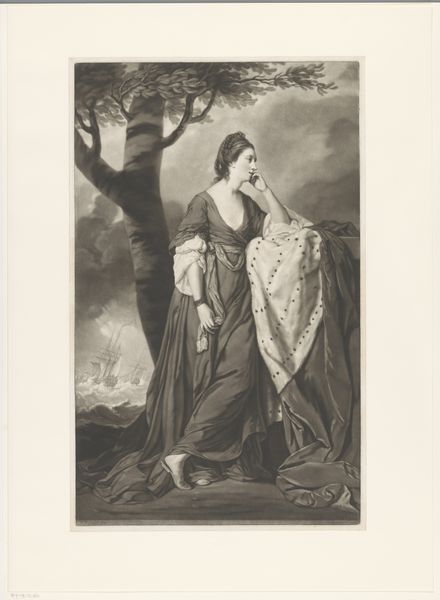

engraving

#

portrait

#

neoclacissism

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 593 mm, width 364 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Edward Fisher’s "Portret van Sarah Lennox," created between 1765 and 1800, using the medium of engraving. The monochromatic palette and neoclassical setting evoke a sense of restrained elegance. What stands out to me is the inclusion of what looks like an allegorical tableau behind the figure, but it makes me wonder: what is going on here? Curator: Let's consider the material conditions that brought this image into being. Engravings, in their reproducibility, democratized access to art. While oil paintings remained largely confined to the elite, prints like these circulated more widely, influencing taste and disseminating cultural ideals. Note the layering; Fisher isn’t just presenting an image but is actively engaged in translating it to different publics, a means of both making and selling an image of the nobility. Editor: So the choice of engraving itself is significant? It makes this portrayal of Sarah Lennox available to a larger audience. Curator: Precisely. It connects directly to the idea of disseminating images of the powerful – projecting a particular vision of aristocratic life while simultaneously creating a market for its consumption. Look at the classical elements, for instance. Who did this symbolism serve, who was likely to want and value it? Editor: That makes a lot of sense. So, the meaning isn’t just in who’s represented but in how it’s produced and distributed, changing it in the process. Curator: Exactly. Understanding the materials and mode of production—engraving—and its intended audience – the emerging middle class – lets us decode how power and representation functioned in 18th-century society. What do you make of this relationship? Editor: I hadn’t considered the active role of the *process* of engraving as it related to its content. Thanks, this was helpful in realizing the layers of meaning imbedded in it.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.