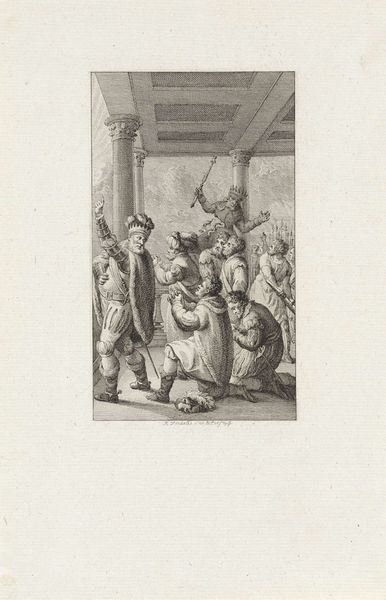

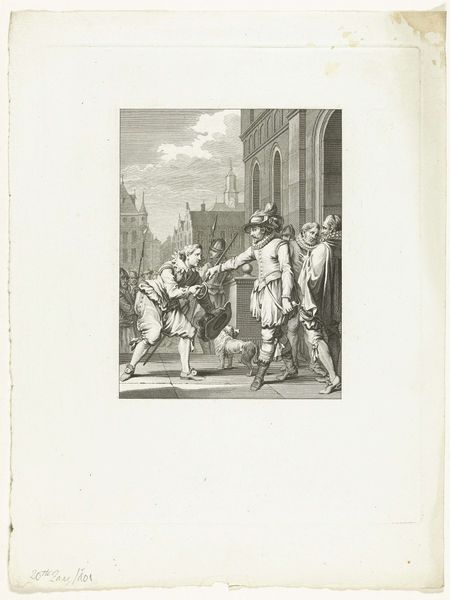

print, engraving

neoclacissism

narrative-art

old engraving style

figuration

old-timey

history-painting

academic-art

engraving

Dimensions: height 205 mm, width 130 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

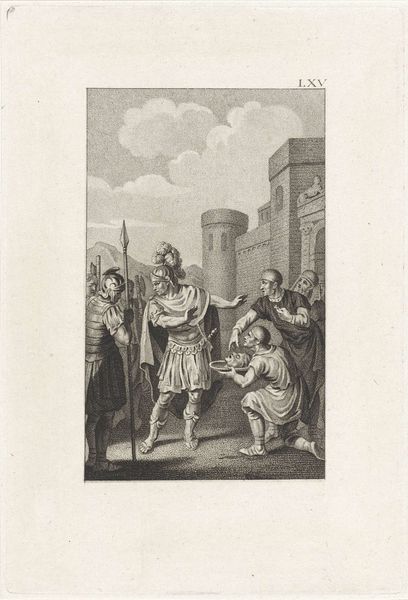

Curator: This engraving by Ludwig Gottlieb Portman from 1804, titled “The Death of Vitellius,” captures a brutal scene from Roman history. Editor: My first impression is of stark drama, even violence, meticulously rendered through the engraver's craft. The starkness reminds me of theater. Curator: Precisely. Look at how the artist utilized line work to suggest the texture of metal armor, the tension in the figures’ muscles, and the draping of fabric. This reflects Neoclassical artists’ fascination with classical techniques. Editor: It is striking how Portman transforms historical violence into a commentary on power. Consider how class and social status were performed. Even in death, Vitellius, once an emperor, is stripped bare and rendered powerless before a largely anonymous mob of figures and representatives of state power. It’s a very critical reflection of power's cruelty. Curator: True, and the print medium is crucial here. Engravings like this made history accessible to a wider audience than monumental paintings could. It allowed these power critiques to circulate amongst various levels of 19th century society, potentially stoking revolutionary ideas. How many of these do you think could be made in a day? It's worth studying the economics around the distribution of these prints in relation to those revolutionary ideas... Editor: The Neoclassical style itself emphasizes civic virtue, and, often in a didactic way, moralizes that very power struggle. But is this a virtue for all or only a select class and kind? We must ask about these forms of exclusions and discriminations when witnessing spectacles such as these. Portman also directs our attention to the complicit and knowing looks of a number of onlookers in the architecture above the scene. The image poses vital questions around the making and unmaking of historical memories and who has a right to define what will become 'history.' Curator: Absolutely. Consider the role of the engraver in this process as well: someone deeply involved in the reproductive economy of the artwork and shaping that 'history.' Editor: I hadn’t considered it that way, thank you for pointing it out. Ultimately, this engraving serves as a reminder of both the physical realities and the socio-political processes inherent in making historical accounts in art. Curator: Yes. It urges us to reflect critically on how artworks are made and also who they might implicate, too.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.