print, engraving

# print

#

figuration

#

genre-painting

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

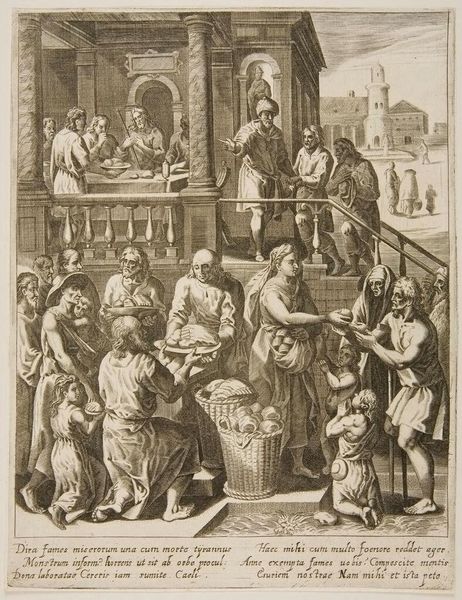

Curator: Let's delve into this captivating engraving, "Vogelverkoper," or "The Bird Seller," created by the artist known as Monogrammist IB between 1525 and 1530. It’s a window into a world viewed through a Northern Renaissance lens. Editor: It has an immediate quiet intensity; the fine lines and the figures' concentrated expressions draw you in. There's a certain intimacy captured in such a small format, like peering into a private moment. Curator: Indeed. As a print, it's part of a broader socio-cultural shift. Prints made art more accessible to a wider audience. Consider the politics of imagery during this period: who controlled the narratives, and who had access to visual representation? Editor: Absolutely, and that accessibility challenges power dynamics. I see in the image’s composition the embodiment of gendered labour and perhaps even exploitation. Note the two women examining the bird, presumably considering a purchase from the bird seller. Their agency is tangible but contained, subject to the economics of the time. Curator: The very act of buying and selling these birds carries symbolic weight. What does it mean to cage a wild creature, to control nature, to trade in freedom? Editor: We could explore this act of commercial exchange through postcolonial theory, touching upon exploitation, control, and how power structures play out through such everyday transactions. The gaze between the figures – is it transactional, equitable, or something more complicated? Curator: And think about the artist's position too. As an artist producing imagery within this framework, are they complicit, critical, or simply reflecting their time? Editor: It prompts reflection on how historical context shapes even seemingly simple scenes. How the role of women as purchasers contrasts with the perceived freedom associated with caged birds makes the viewer question what freedom really entails within structures of inequity. Curator: Precisely, it forces us to consider art’s enduring capability to reflect—and refract—our understanding of our society and its development. It reveals that the concerns of people living five hundred years ago are really not so alien. Editor: A tiny picture sparks major discussions. That’s why exploring the nuances is essential, isn’t it?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.