print, woodblock-print

# print

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

ukiyo-e

#

woodblock-print

Dimensions: height 359 mm, width 242 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

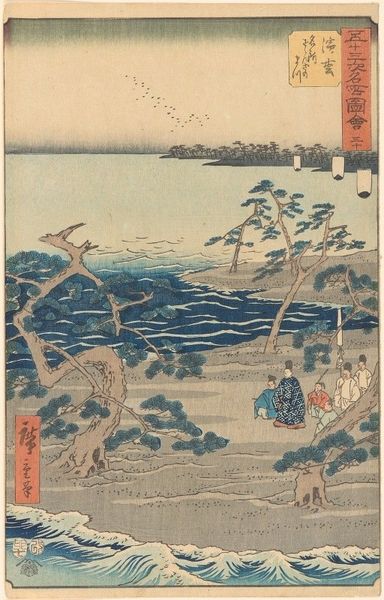

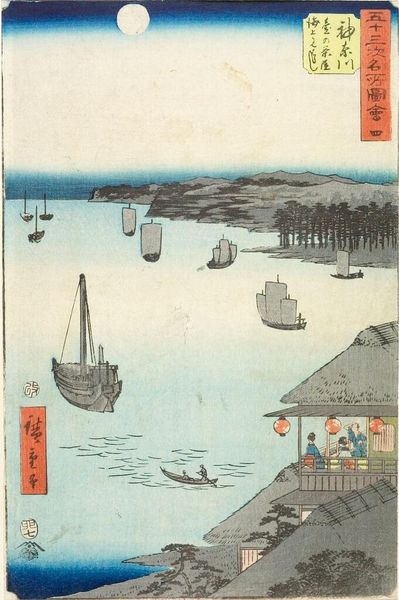

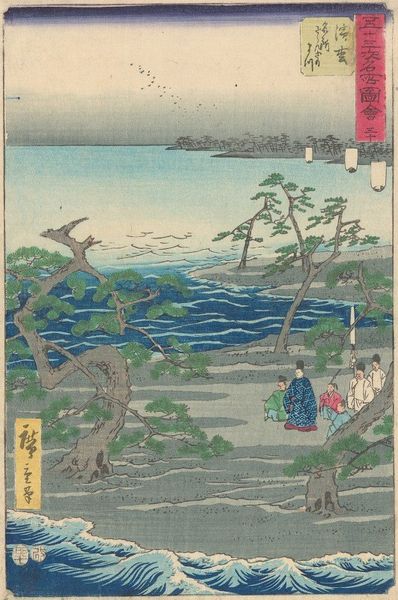

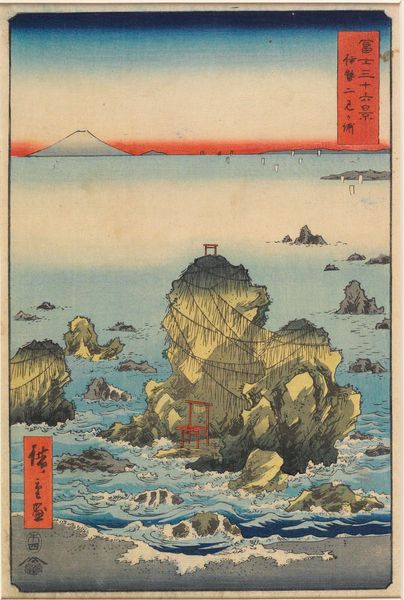

Curator: This tranquil woodblock print by Utagawa Hiroshige (I) is titled "The Elegant Prince Genji at Suma," created around 1853. Editor: My immediate feeling is melancholy. The subdued palette evokes a sense of isolation, even longing. It's a seascape, but feels introspective. Curator: That feeling isn't accidental. Prince Genji, the subject, was a fictional character exiled to Suma in "The Tale of Genji," a classic of Japanese literature. The landscape, then, reflects his internal state of exile and introspection. The ukiyo-e print tradition elevated such subject matter. Editor: Precisely! The boats in the distance take on a symbolic weight; freedom and unattainable desire on the horizon. Are those stylized pine trees clinging to the cliffs intentional nods to endurance and resilience? I sense something particularly Japanese about that quiet stoicism. Curator: Definitely. That's part of a larger tradition of art acting as a subtle mirror to events and societal expectations. While landscape was a common theme in ukiyo-e, placing Genji, this fictional but culturally potent figure, within it creates a political space, offering commentary on power and privilege in Japanese society. His story resonated broadly, as an allegorical commentary about Japanese imperial rule. Editor: That interplay of reality and fiction adds a rich dimension to its emotional impact. It makes the exile both personal, yet larger than life. Is there something telling about how small the artist renders the characters visible along the coast? They seem at the mercy of larger forces, both natural and societal. Curator: Yes. Think of this composition in terms of landscape acting as a theater for social narratives, influencing viewers to contemplate the social structures and injustices faced during the late Edo period in Japan, making his exile less personal and more universal. Hiroshige makes the political personal. Editor: Absolutely, now, observing that interaction—it adds another layer of resonance and perhaps makes the melancholy more powerful. Thank you. Curator: Indeed, understanding how imagery is tied to cultural and socio-political narratives truly enriches our perception of art.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.