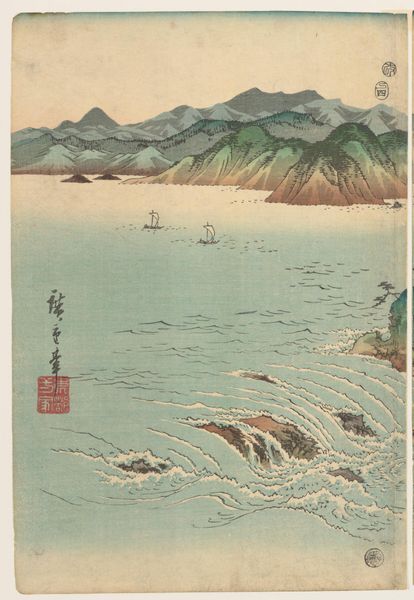

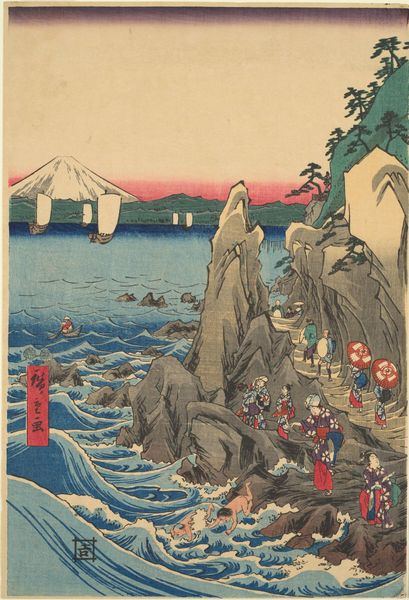

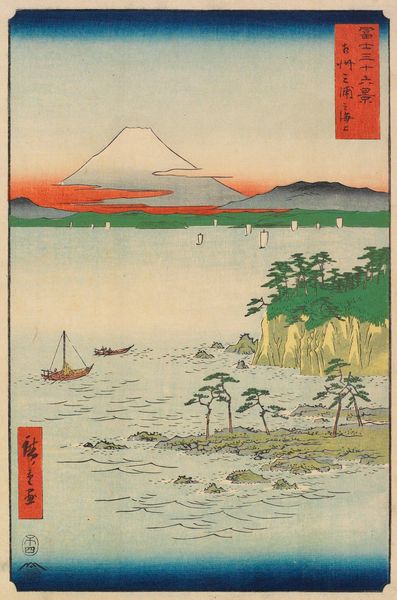

Dimensions: 13 1/4 × 8 11/16 in. (33.6 × 22 cm) (image, vertical ōban)

Copyright: Public Domain

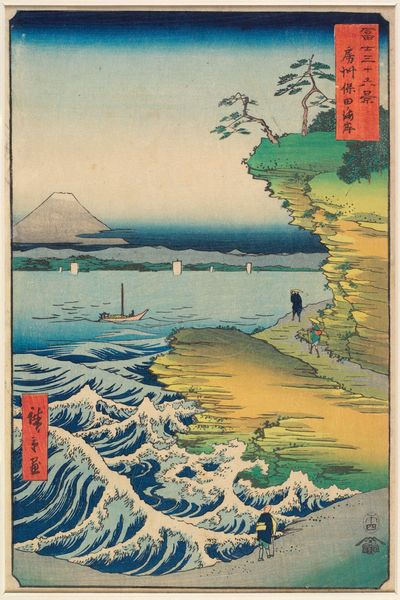

Curator: Welcome! We’re standing before Utagawa Hiroshige’s "Futamigaura in Ise Province," likely created around 1858. It’s a color woodblock print, a stunning example of ukiyo-e landscape art, here at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. What strikes you first about this print? Editor: The contrast, definitely. The soft, almost dreamlike pastel sky against the rugged, wave-battered rocks below—it feels both serene and a little ominous. I'm also intrigued by the torii gates perched atop those formations. Curator: Excellent observation. Structurally, the composition draws the eye upwards: the surging sea, the anchored rocks crowned by the torii gates, leading to a quiet horizon line. Notice how Hiroshige uses color gradation in the sky—from deep blues at the top, bleeding into vibrant orange along the horizon where we also spot a distant Mount Fuji. Editor: I am especially interested in these 'married rocks' or Meoto Iwa, and the rituals associated with them. This piece presents a powerful visualization of Shinto beliefs embedded within this locale. We can consider the significance of these torii gates acting as portals, signifying transitions between mundane and sacred spaces, shaping spiritual journeys and social cohesion. Curator: Precisely. Consider the meticulous technique employed in the rendering of textures: the rough surfaces of the rocks contrasted with the smooth planes of the water and sky. Semiotically, the gates also signify prosperity and happy marriage; look closely to observe that the larger rock representing the husband is linked to the smaller wife one by a heavy rope of straw. This emphasizes the bonds central to marriage—a metaphor that's literally cast in stone and rope. Editor: Yes, and this symbology interacts powerfully with our understanding of gender and social responsibility in the mid-19th century. Think, for instance, of the material realities—the societal expectations and their attendant constraints— of women during the Edo period, and reflect how this imagery normalizes marital expectation through the rocks and ropes. Curator: I see your point. Though this might simply illustrate social constructs, I would be cautious in framing it solely in the negative light, due to other signs of economic progress, especially in art creation and availability as evidenced by these very woodblock prints. Regardless, your take reminds us that art often is a dialogue about identity, expectation and social contract. Editor: That’s right. Considering Hiroshige’s work through this lens invites a richer exploration. It shows how art echoes and shapes the narratives of its time. Thank you for bringing Hiroshige and the intricacies of "Futamigaura in Ise Province" into such sharp focus.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.