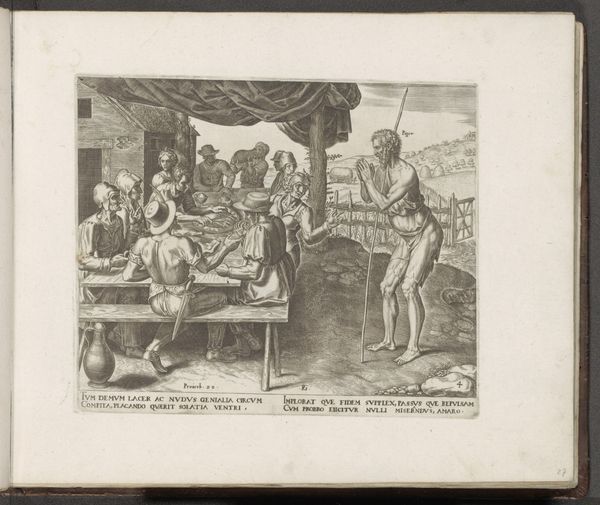

print, engraving

#

allegory

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

nude

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 157 mm, width 215 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

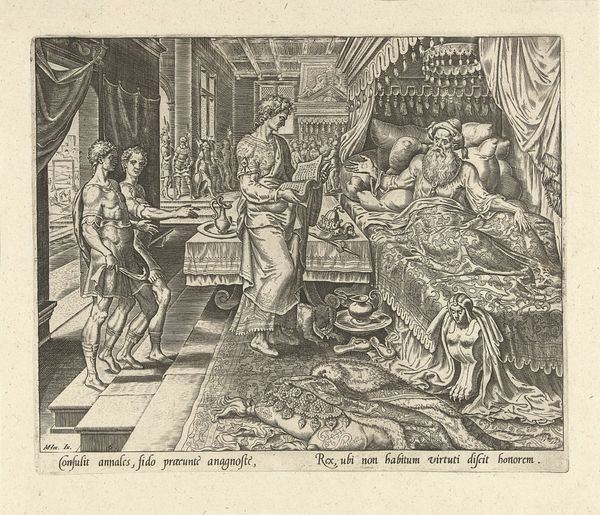

Curator: Let’s turn our attention to an engraving currently listed as Anonymous, created sometime between 1558 and 1656. The Rijksmuseum titles it “Suzanna en de ouderlingen” or Susanna and the Elders. What’s your first take on this, given the texture of the piece? Editor: The contrasting grayscale really brings a specific intensity to the leering nature of the two men against the serene posture of Suzanna. The engraving technique here really drives that mood home with sharp delineation. It’s powerful, almost jarring. Curator: It depicts the biblical story of Susanna, falsely accused by these two elders after she refuses their advances. It became a popular subject in art, embodying themes of virtue, power dynamics, and social injustice that were definitely relevant during that period. Editor: Right, and look at the setting itself. This ornate fountain and surrounding structure… even the materiality of the fountain—presumably stone and carefully placed foliage, they aren’t just decorative. It really situates Susanna's innocence within a fabricated world of wealth and potential. Curator: Absolutely. It's staged to amplify the contrast between Susanna’s purity and the elders' corrupted positions. You can really dig into the implications about institutional power here—the male gaze, law and the role of women's bodies in religious art all coming into play. It’s heavy with social commentary, made all the more resonant through circulation as a print. Editor: How interesting that this story became widespread as a print versus only being available as a painting for the upper class, this print really implicates the viewer, or the person consuming the object in the role of voyeur and judge. It shows that mass production has a big influence on the reception and impact on a larger population. Curator: A brilliant observation! It raises key questions about audience reception and shifts in moral judgement that coincide with art becoming increasingly democratized and more reproducible through processes like printmaking. Editor: And as an engraving, that precision work required such intensive labor... the material itself holds that tension, the weight of the story and of those making it being pulled together onto the page. That act of creation is inherently linked to the commentary we are both now delivering on it. Curator: Indeed, a tangible testament to those stories that end up transcending social class and entering popular knowledge. Editor: Makes you think about where things may go when translated from material like that to this new era of algorithm-driven art generation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.