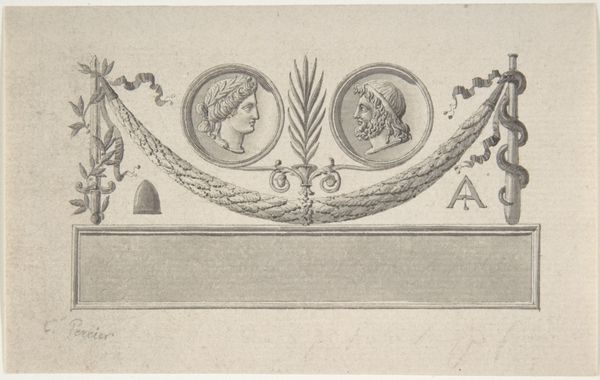

engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

old engraving style

#

figuration

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

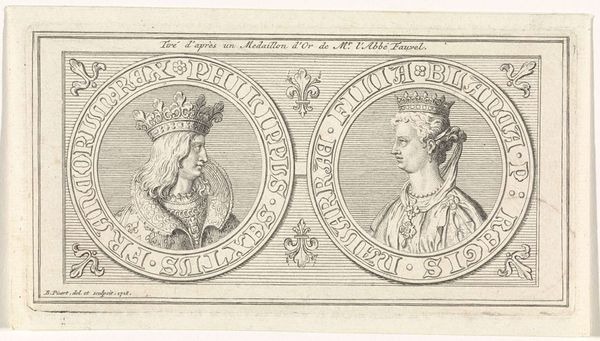

Dimensions: height 72 mm, width 135 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have "Portraits of Anne of Brittany and Mary Tudor," an engraving likely made between 1683 and 1733 by Bernard Picart. It’s quite fascinating to see these historical figures rendered with such detail in this particular style. What are your initial thoughts? Editor: There's a strong sense of formality, even with the allegorical figures flanking the portraits. It evokes a feeling of looking back, not just at the women themselves but at the expectations and limitations placed upon them as queens. The limited palette creates a sense of distance. Curator: Absolutely. This piece exists within a long tradition of portraiture designed to reinforce power and dynastic claims. Anne of Brittany, for instance, was queen consort of France, not once, but twice! Picart's engraving highlights her regal status, freezing her in a moment of perceived timelessness, as the sitter of politically motivated marriage. Editor: Yes, but these weren't just personal portraits; they were crafted for public consumption, contributing to the narratives and propaganda of their respective courts. How interesting to consider who these women were as human beings within these very calculated representations of power. It also makes you wonder how much control did they truly wield over their lives versus what was forced onto them? Curator: An important point. The setting of each figure—a landscape and a cherubic figure—seems laden with symbolic intention that would be worth more historical scrutiny. We might ask, what would audiences at the time have made of such conventional staging? Editor: And it's not just about their historical positions; the details of their dress, the tilt of their heads – these are all elements that reinforce gendered expectations. Even in this static engraving, we can dissect how women of power were presented, and often confined, by the prevailing social structures. One positioned near foliage, nature—birth and fertility— the other flanked with a cherub above a skull, as if suggesting they are divinely associated to death and legacy? It could trigger complex debates on cultural expectations, too. Curator: Yes, looking at Picart’s source material and the conventions around portraiture can lead to a wider appreciation of the art and its role within culture. Thank you, those have all been quite salient observations. Editor: Thank you. These images may appear simply as historical depictions, but beneath the surface lies a deeper exploration of power, representation, and the ongoing negotiation of identity through art.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.