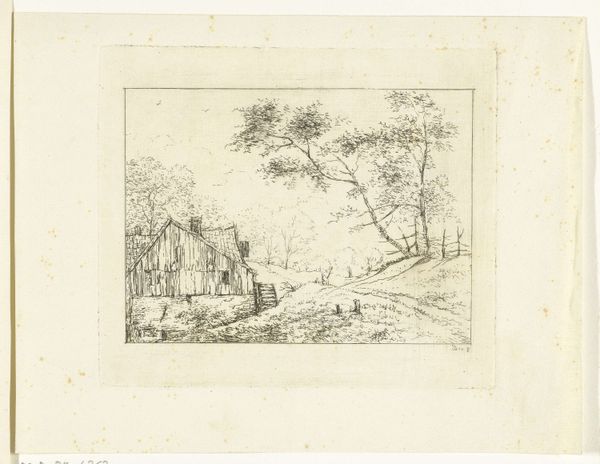

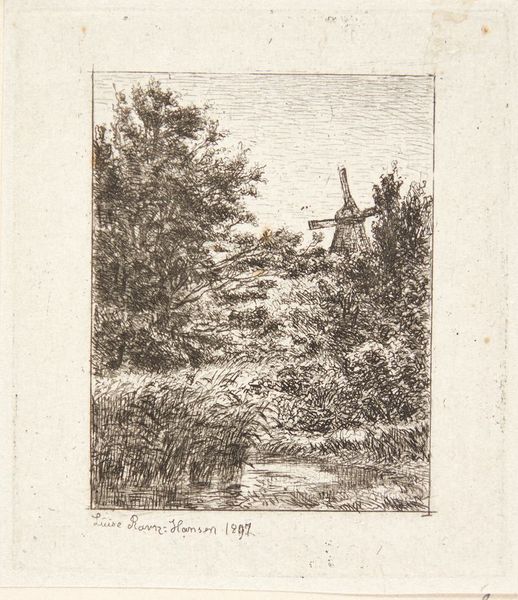

drawing, paper, pencil

#

pencil drawn

#

tree

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

#

pencil sketch

#

landscape

#

paper

#

pencil

#

cityscape

#

tonal art

#

realism

Dimensions: height 275 mm, width 205 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Pieter Barbiers's pencil drawing, "Gezicht op 's-Hertogenbosch", from between 1808 and 1848, really captures a moment of quiet observation. There's a sense of serenity, but also of distance, like we're seeing the city from afar, maybe even through rose-tinted glasses. What's your read on this drawing? Curator: It’s interesting you mention the "rose-tinted glasses." Drawings like these were often commissioned by the rising merchant class, eager to see their towns portrayed with a certain dignity. How does this idealized depiction, and the very act of commissioning such a work, serve their social and political ambitions? Editor: I hadn't thought of that! So, it’s not just a pretty picture; it's about creating a certain image of the city, reflecting the patron's values and aspirations. Were these drawings like propaganda, then? Curator: Perhaps propaganda is too strong a word. Consider the Neoclassical elements influencing the composition, the ordered layout, the focus on prominent structures. This reflects an appeal to reason, order, and civic pride – virtues celebrated by the emerging elite who held political power. And realism plays a key role – how can that support that appeal? Editor: By presenting the city as prosperous and well-organized, reinforcing a sense of stability and control. It makes you wonder about what’s left out. Curator: Precisely! And those elisions, those unspoken aspects, are just as critical to understanding the politics of imagery. Now I see why history students are so interesting. Editor: Well, I never thought a pencil drawing could tell you so much about social class and political aspirations. It really changes how I see these kinds of landscapes now! Curator: Indeed, it's about understanding art as a participant in broader social conversations, rather than an isolated aesthetic object.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.