Drie schetsen van een vrouw met juk, man met emmer en een pelgrim Possibly 1690 - 1799

0:00

0:00

drawing, paper, pencil

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

pencil sketch

#

figuration

#

paper

#

pencil

#

genre-painting

Dimensions: height 150 mm, width 212 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

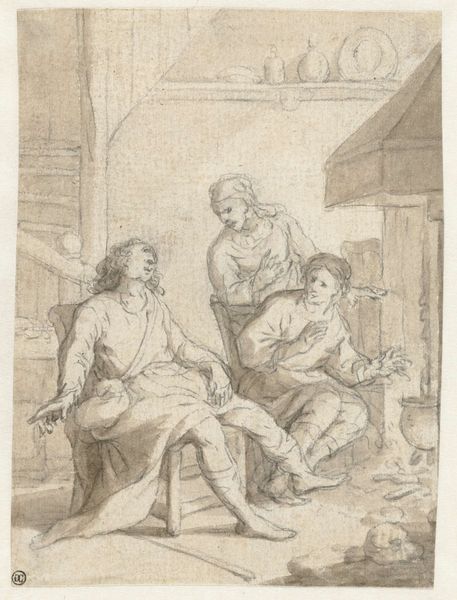

Curator: Looking at this pencil sketch, I am immediately struck by its casual elegance. Editor: I see an almost ethereal scene… ghosts from a sepia-toned past haunting ordinary labors and journeys. It’s the barest whisper of people doing things. Curator: It's catalogued as "Three Sketches of a Woman with Yoke, Man with Bucket, and Pilgrim" by Jan Baptist Lambrechts, created sometime between 1690 and 1799, a flurry of the baroque if you will. These were rapidly drawn studies on paper in pen, showing figures carrying heavy weights. Editor: Weights both physical and metaphorical, perhaps? The pilgrim, with what seems to be a scallop shell prominently displayed – that emblem suggests not just a journey, but spiritual seeking. What kind of burdens of life or soul did Lambrechts want to explore, sketching in brief glimpses? Curator: Scallop shells as pilgrim badges were popular back then as signifiers of the Apostle Saint James, thus faith became a core of a traveler’s baggage in the 17th and 18th century Netherlands. Then again, each figure carries their burdens differently; the woman's shared evenly across a yoke and the bucket guy carrying more lightly only a single weight. These are archetypes here, yes? Editor: It makes me wonder about those implied narratives; all journeys imply transformation. Does the water-carrier offer sustenance? Does the pilgrim find enlightenment, relief from his symbolic burden? Are the buckets metaphorically heavy as their bearers’ worries? The lightness in style allows the viewers to finish their narrative, perhaps that is Lambrecht’s trick! Curator: Right, while his contemporaries crafted expansive tapestries or complex landscapes, he zoomed in, so to speak, focused only on key, perhaps moralising motifs, within these characterful bearers. The Baroque, you see, even at its most seemingly plain and quick like here, spoke about an underlying, emotional core of a narrative. Editor: Exactly! Now when I see these pencil marks I don't simply witness figures in the sketch but imagine a moment between waking and sleep where symbolic shapes are moving freely with their hidden intentions exposed at once for everybody. Curator: And yet the openness here helps the drawing speak so clearly across the centuries to each of us, still making the stories felt instead of simply being seen. Editor: Well said. Let’s hope listeners today embark with renewed eyes, onto the next stage.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.