print, engraving

#

portrait

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

pencil drawing

#

portrait drawing

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 231 mm, width 142 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

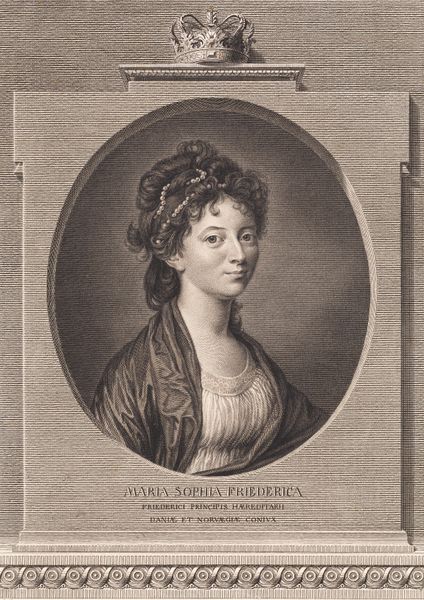

Curator: Willem van Senus rendered this engraving of "Portret van Maria Duyst van Voorhout" sometime between 1822 and 1826. The original rests here in the Rijksmuseum. Editor: She seems a little wistful, don’t you think? It’s the eyes perhaps. There’s a softness to them that contrasts with the formality of the setting and her pearls. Curator: Considering the context, the print, made much later after the original subject's life, becomes particularly intriguing. Van Senus likely drew upon earlier portraits or sources to craft this image. I am always curious about the paper. It seems like a sturdy rag paper typical of the time, allowing for crisp lines. The process itself of creating such an engraving speaks volumes about skilled labor of artisans involved. Editor: Absolutely, and that process inherently layers meaning onto the image. The choices – what to include, what to emphasize – all contribute to constructing an identity. I am struck by how Maria Duyst is positioned within a very specific ideal of feminine beauty of the period; the carefully arranged curls, the delicate jewelry and her positioning within the composition tells a clear narrative about wealth and status. Curator: Yes, that emphasis brings up questions of accessibility and consumption, too. Prints like these were often reproduced and distributed, broadening access to images of elite figures. Consider the networks involved: the printmakers, publishers, distributors, and the consumers. These networks created dialogues of fame and influence. Editor: The availability and distribution you mention underscores the role such images played in perpetuating social hierarchies. What does it mean for women in particular that this became a commodity, an object that's bought and sold, to shape norms? Curator: That interplay between artistic labor, material production, and its effect is worth further thought, and reveals that while portraits preserve likenesses, the method itself participates to make them active signifiers. Editor: Agreed, thinking of it more critically helps us explore representation, gender, and the subtle negotiations within Dutch society in her time. It brings an entire new vision, thank you! Curator: Likewise, considering how artisans utilized readily available resources, from engraving tools to paper and distribution channels is essential for any responsible analysis. A fruitful conversation, indeed.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.