Copyright: Public domain

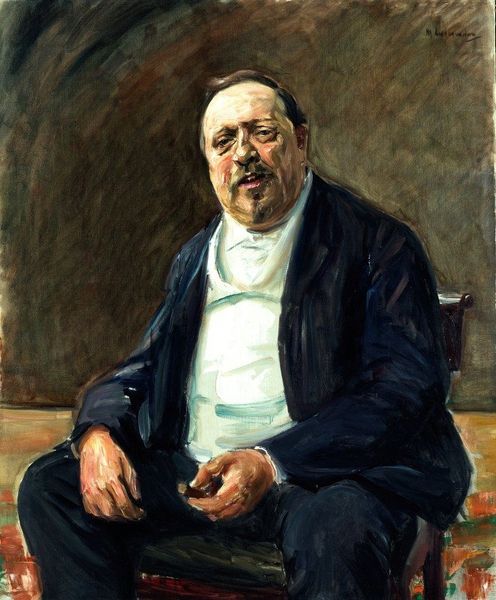

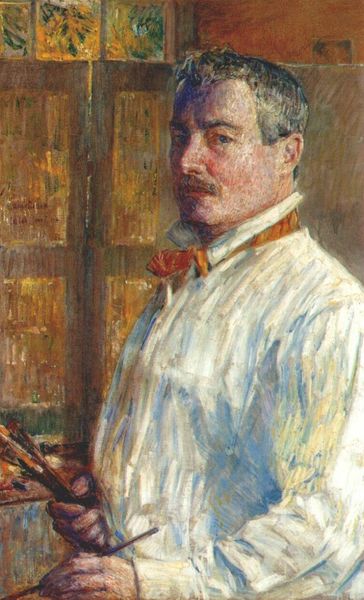

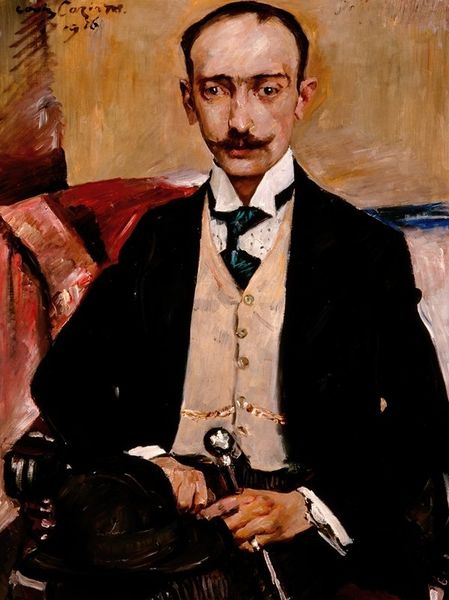

Editor: Lovis Corinth’s “Portrait of the Pianist Conrad Ansorge,” painted in 1903, gives us a glimpse into the sitter's world, but it’s the oil paint itself that catches my eye. The way Corinth applies it, almost raw in places, really speaks to the energy of the subject. What stands out to you? Curator: The visible brushstrokes are exactly where I’d start. They aren't just a stylistic choice. Think about what it means to represent someone like Ansorge, a celebrated pianist, in this manner. The painting foregrounds the physical act of its making. How does the process of depicting the pianist become a key element in understanding his profession, also an act of production? Editor: So, the painting itself becomes a performance, similar to a piano recital? The visible labor connects to the labor of the pianist? Curator: Precisely. And consider the social context. Corinth is challenging the traditional hierarchy between high art – portraiture of important figures – and what was then considered mere craft, the manipulation of materials. The oil paint becomes a tool, almost like a pianist's fingers on the keys. Editor: That's fascinating. It never occurred to me to see the materiality of the paint as such a vital link between the artist and the subject, as it’s not merely representational. The painting’s medium thus also serves as commentary about Ansorge's life. Curator: Absolutely. And, in a way, Corinth anticipates a shift in how we value artistic production, placing emphasis on process and the materiality of art itself, as labor becomes visible. This creates new social and aesthetic implications for both artist and subject. Editor: I’ll definitely view Corinth's work differently now, thinking more about labor and its impact. Thanks! Curator: My pleasure. Looking at art this way helps reveal hidden aspects of the piece and of history itself.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.