carving, print, daguerreotype, photography

#

carving

# print

#

landscape

#

daguerreotype

#

ancient-egyptian-art

#

photography

#

carved into stone

#

geometric

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

history-painting

Dimensions: 23.4 x 30.1 cm (9 3/16 x 11 7/8 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

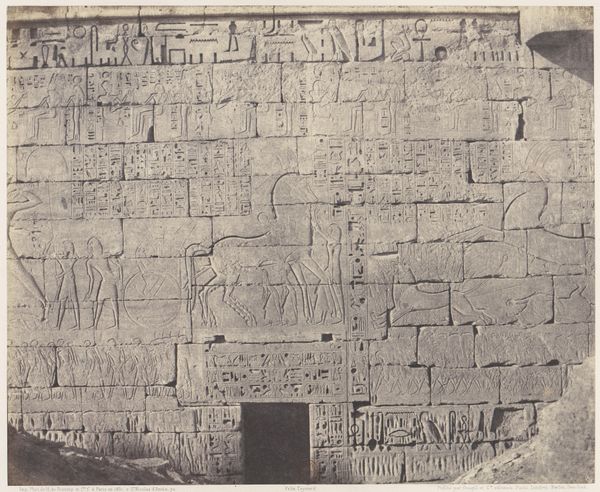

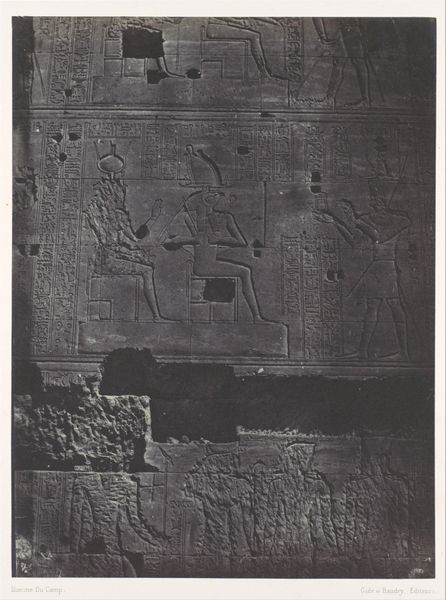

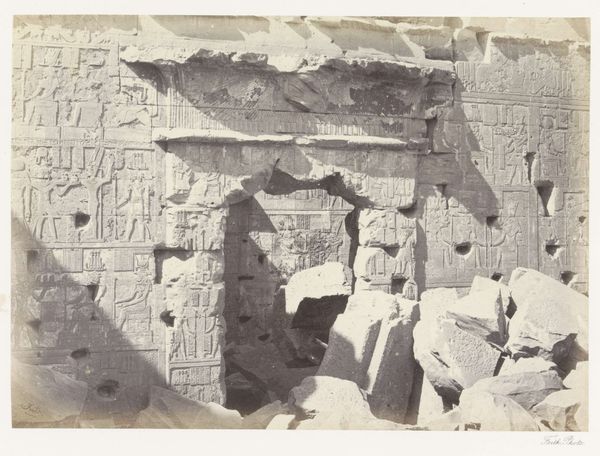

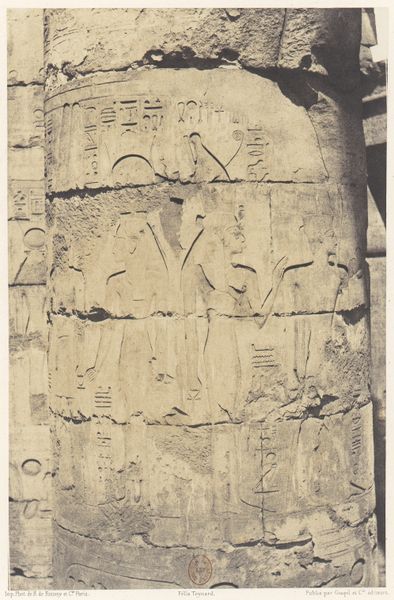

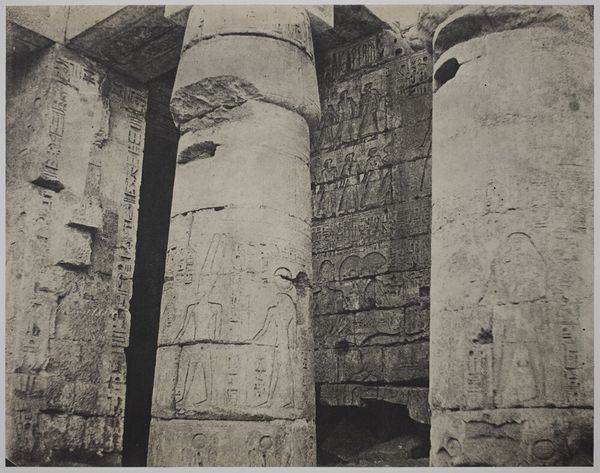

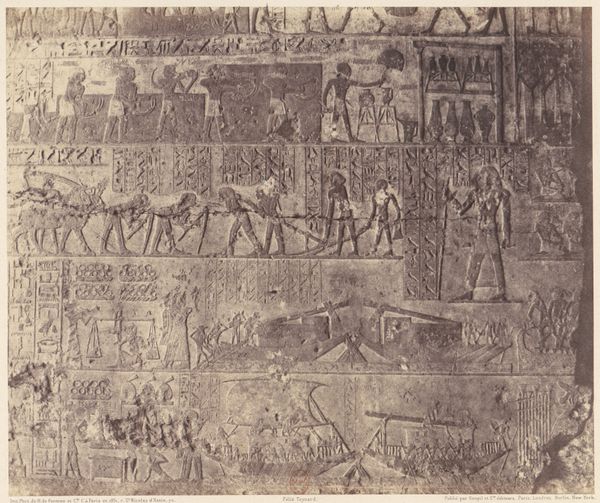

Curator: This is "Medinet-Habu," a daguerreotype crafted by John Beasley Greene in 1854. Currently, it resides here at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: Immediately striking. The density of the carvings feels monumental and a little intimidating. There's an undeniable power in these walls; they seem to silently witness centuries of history. Curator: Precisely. Greene's composition emphasizes the abstract qualities of the hieroglyphs. The photograph reduces the temple wall to a surface of textured marks, almost divorced from their original narrative function. Notice how the light rakes across the surface, accentuating the play of form and shadow. Editor: Yet, the narratives are crucial, aren't they? This image speaks volumes about Western orientalism of that period. Greene, in choosing this subject, participates in the colonial gaze, documenting and, in a way, claiming a piece of Egyptian history for a Western audience. Curator: I can see your point. But also consider his mastery of the photographic process. The sharpness and clarity achieved with the daguerreotype technique render incredible detail, turning the monumental into the meticulously observed. Greene offers us not just documentation but a sophisticated visual experience. Look closely at the geometric distribution of forms across the stone. Editor: Agreed, but let's not overlook the political dimension inherent in documenting another culture’s history. Who is Greene photographing for, and what power dynamics are at play when these images are disseminated in Europe and America? Curator: Well, it's irrefutable to disregard such social implications. Greene was fascinated by ancient languages. His close examination shows a commitment to seeing beauty, symmetry and structure. Editor: Absolutely. It pushes us to grapple with uncomfortable truths. But, seeing these ancient forms frozen in time by a contemporary process ignites my respect for the ingenuity of early photography as well as my need for it to not gloss over who it was meant to reach in the 1850s.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.