albumen-print, etching, photography, site-specific, albumen-print

#

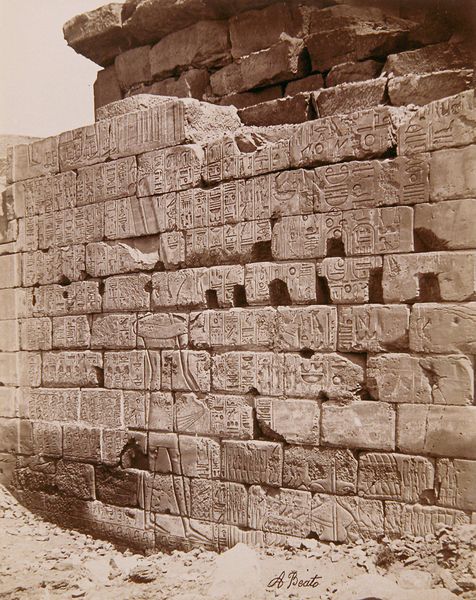

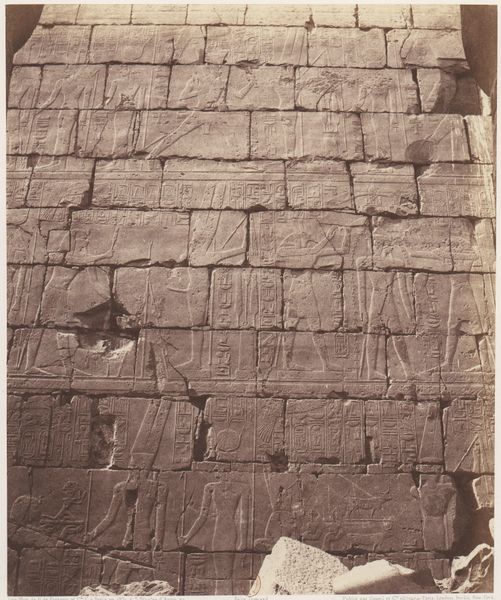

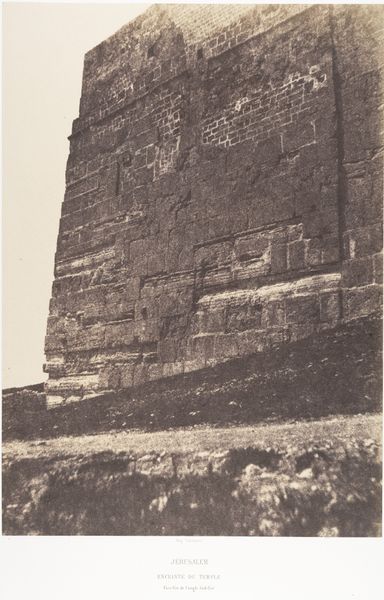

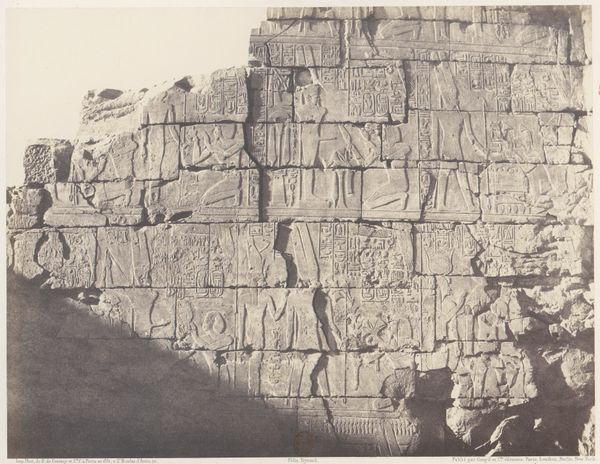

albumen-print

#

excavation photography

#

etching

#

landscape

#

photography

#

derelict

#

carved into stone

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

site-specific

#

france

#

cityscape

#

albumen-print

Dimensions: 8 13/16 x 11 3/16 in. (22.38 x 28.42 cm) (image)11 x 14 in. (27.94 x 35.56 cm) (mount)

Copyright: Public Domain

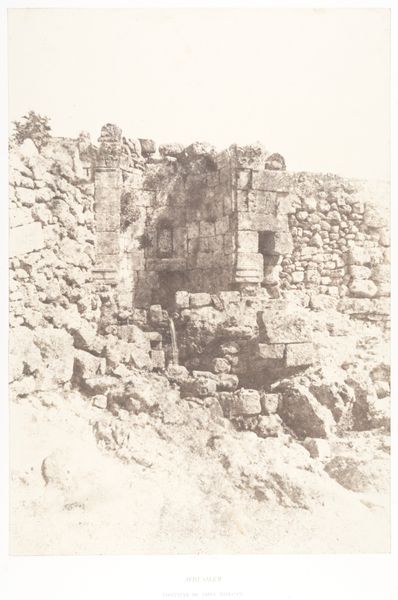

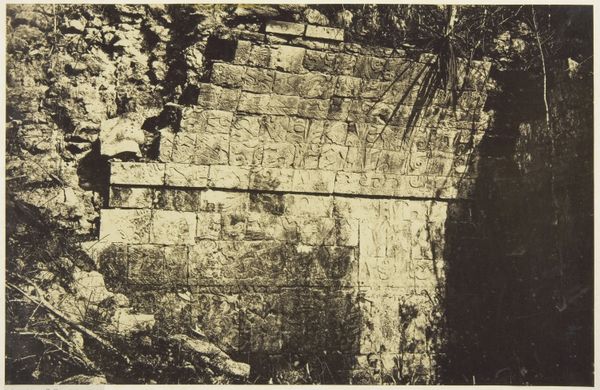

Curator: This is Félix Bonfils' photograph, "Mur cyclopeen a Baalbek," dating from the 1870s. It's an albumen print currently residing at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. What are your initial impressions? Editor: Monumental, certainly! The scale conveyed here is impressive, verging on intimidating. The sepia tones emphasize the age and apparent solidity of the wall itself. Curator: Indeed. Bonfils, a French photographer, captured this image in what is now Lebanon. During this period, archaeological documentation was very much entangled with colonial agendas, which framed the Levant as a source for European history. Photography played a critical role. Editor: Yes, and you can see that in how the photographer uses shadow and light to accentuate the texture of the massive stones. The wall dominates the composition, angled dynamically to create a sense of both its height and depth. The roughhewn surface contrasts beautifully with the delicate plant life encroaching at its base. Curator: Exactly. The 'cyclopean' wall—referring to the mythical giants who supposedly built such structures—highlights the exoticism ascribed to these sites by Europeans at the time. Bonfils wasn't just documenting, he was visually participating in shaping public understanding and political imagination. The albumen process renders every detail. Editor: And allows for incredible tonal range, doesn't it? From the almost-white highlights to the deep shadows, the materiality is beautifully rendered. It underscores the contrast between the geometric regularity of the blocks and the organic chaos of the plants—nature versus man, or perhaps nature reclaiming man's endeavors. Curator: The strategic framing—centering the massive scale while acknowledging the erosion and decay—invited the 19th-century European viewer to ponder the grand sweep of time and the transience of power. The ruin became evidence and monument all at once. Editor: The photographer is quite clever, wouldn't you agree? He transforms mere stones into a meditation on power, decay, and the grand passage of time itself, achieving incredible results in what seems like simple documentation. Curator: Precisely, and it’s through studying such images we are enabled to discuss the complicated narratives of colonialism and cultural memory embedded within. Editor: Yes, thank you. This close look at Bonfils’ photography certainly sheds a new light on how we perceive the past through artistic construction.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.