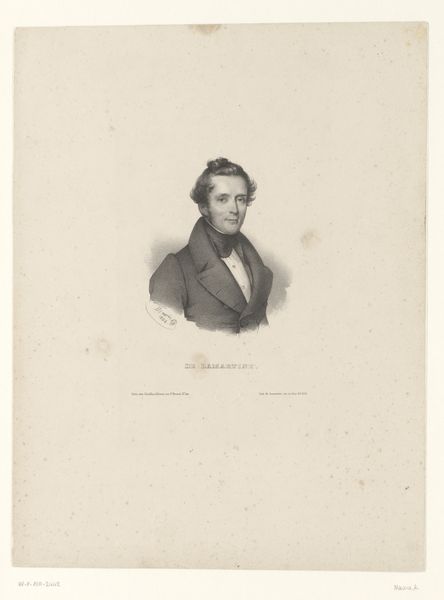

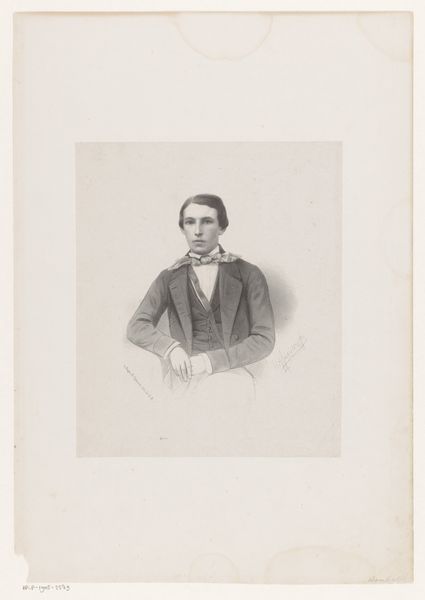

drawing, print, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

# print

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 230 mm, width 137 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

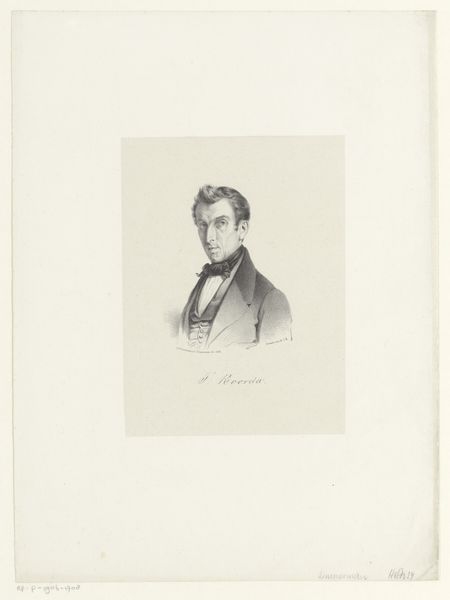

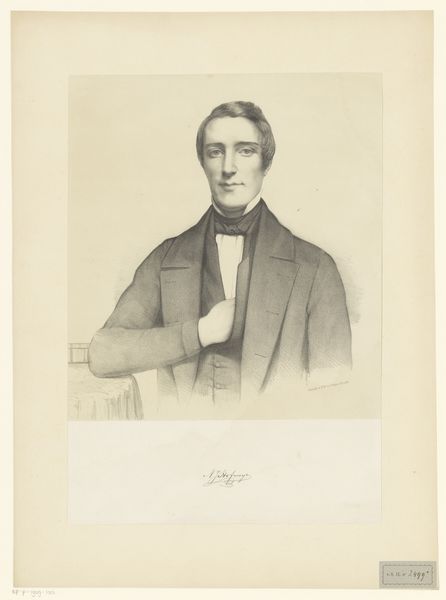

Curator: Good morning. Today, we are looking at a piece entitled "Portret van Johan de Wal," dating roughly between 1848 and 1886, a drawing subsequently made into a print and engraving by Dirk Jurriaan Sluyter. It resides here, in the collection of the Rijksmuseum. Editor: Immediately, I get a very… formal vibe? Austere. It's a rather severe portrayal, though skillfully executed. There’s a stillness that feels almost… unsettling, don’t you think? Curator: Indeed. The formal style of the portrait reflects the social status Johan de Wal held within 19th-century Dutch society. Portraits like this were frequently commissioned to project an image of respectability and intellect. Note the symbolic weight in his posture and the subdued tones. These were intentional choices that would resonate with contemporary viewers familiar with codes of social standing. Editor: The way the artist has used light is quite fascinating. It almost seems to carve out his features, especially his face and the way he’s holding the book or papers? It seems he is quite stoic, without almost any emotion in his expression. It's almost like the artist intended to present him as unreadable, some form of blank canvas perhaps. Or is it a very studied portrayal of control? Curator: Very astute! Consider the historical context; Realism was coming into vogue, prioritizing the depiction of subjects as they truly appeared, yet tempered by social conventions. A neutral expression, especially for men of standing, signified reasoned thought, power, and the absence of frivolous emotion. It signaled someone in control of themselves and therefore fit to lead or make sound judgements. His subtle gaze is also interesting – does it hold a challenge, or a polite deference? Editor: I find myself more intrigued by what's not said, you know? What he is thinking, his story. He has this sense of guardedness, which is telling in itself. I think my mind fills in a back-story from just the stillness the artist captures. Maybe everyone felt that pressure, being memorialized. That he’ll forever be still… almost entombed? It feels so… fixed. Curator: Yes, an engraving offers a peculiar form of immortality. These portraits served as powerful cultural symbols, reinforcing societal expectations and signaling continuities through generations. Perhaps, seeing this piece, we ourselves consider how portraiture – in our age of selfies – still operates in shaping self-perception and social presentation. Editor: I wonder if de Wal himself knew how potent this would be. A frozen moment echoing over a century. Intriguing.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.